AP Syllabus focus:

‘European exploration and conquest were driven by economic rivalry and military competition among European states.’

European nations entered the Atlantic world competing fiercely for wealth, territory, and global influence, driving exploration, conquest, and colonization that reshaped power balances and accelerated transoceanic expansion.

Rival Empires: Economic and Military Competition

Intensifying Competition in Europe

By the late fifteenth century, Europe was characterized by dynamic political rivalries among emerging nation-states such as Spain, Portugal, France, and England. These kingdoms sought to strengthen their positions relative to one another, and transoceanic exploration became one of the most strategic tools for achieving this. Economic pressures, combined with military ambitions, encouraged rulers to sponsor expeditions that could secure advantages in global trade and territorial claims.

The expansion of centralized monarchies meant that governments could increasingly fund voyages, compete for maritime supremacy, and project power beyond the European continent. This wider geopolitical context made the Atlantic world a stage upon which European powers contested influence.

Economic Rivalries and the Search for Wealth

The desire to outcompete neighboring states fueled efforts to obtain direct access to Asian luxury goods, African gold, and American raw materials. Several interconnected motivations drove this economic competition:

Control of trade routes to bypass Venetian and Ottoman intermediaries.

Acquisition of precious metals, particularly silver and gold, to strengthen national treasuries.

Access to new markets where European goods could be exchanged profitably.

Expansion of mercantilist strategies, which emphasized accumulating wealth by dominating trade flows.

Mercantilism, a policy framework in which states sought to maximize exports and minimize imports to grow national wealth, became a guiding economic philosophy.

Mercantilism: An economic system in which governments regulate trade to increase national power by accumulating wealth, especially gold and silver.

Following the definition above, it is important to recognize that economic motives did not operate in isolation but were woven tightly into larger political and military dynamics.

Technological Change and the Race for Maritime Dominance

Advances in maritime technology—such as the caravel, lateen sail, and improved astrolabe—enabled states to send expeditions farther and more safely. These innovations offered strategic advantages to early adopters.

Portugal pioneered early Atlantic exploration along the African coast, seeking dominance in the Indian Ocean spice trade.

Spain rapidly caught up by sponsoring Columbus in 1492, claiming vast territories in the Americas.

France and England, initially slower to invest, soon recognized the geopolitical risks of falling behind, prompting their own exploratory ventures.

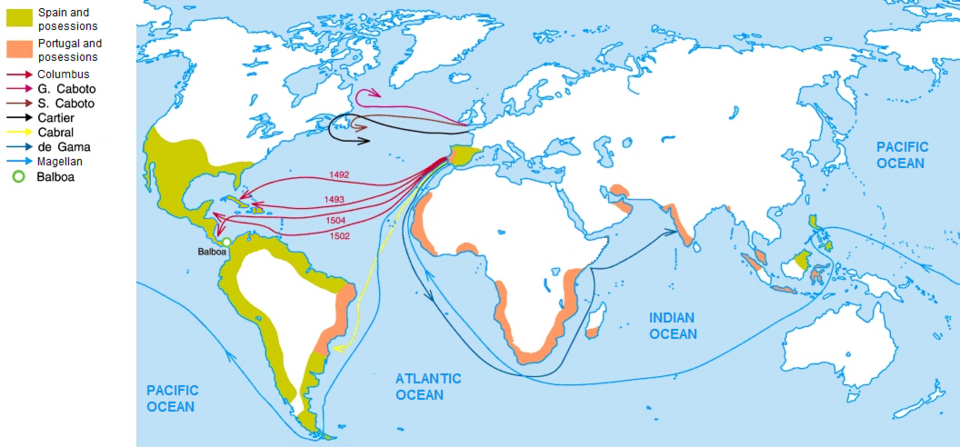

This map illustrates the principal sea routes taken by European explorers during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It highlights how Portuguese and Spanish voyages, followed by other European powers, opened direct access to African, Asian, and American markets. The map includes routes and regions that extend beyond the AP focus, but they help demonstrate the broader competitive context of European maritime expansion. Source.

Military Ambition and Imperial Rivalries

The competition was not purely economic; it was fueled by the desire for military advantage and strategic positioning. European states viewed overseas territories as extensions of their geopolitical power and sought to prevent rival empires from achieving dominance.

Key elements of this military competition included:

Securing fortified settlements to protect shipping lanes.

Establishing naval power to defend imperial claims.

Deploying soldiers and conquistadors to conquer Indigenous populations and control territory.

Using alliances or rivalries with Native groups to strengthen military presence.

Spanish conquests in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Peru, backed by military force and technological advantages such as steel weapons and cavalry, elevated Spain to the position of Europe’s leading imperial power. This success alarmed competing states, spurring them to accelerate their own expansion plans.

Diplomacy, Treaties, and the Struggle for Recognition

As territorial claims multiplied, European states also relied on diplomacy to assert control. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), negotiated between Spain and Portugal under papal authority, divided the non-European world along a longitudinal line. While this treaty reduced conflict between these two powers, it intensified resentment among excluded nations such as England and France, who rejected the agreement and pursued their own claims.

Territorial disputes continued to shape relations among European powers. Rival empires often sought to undermine one another's settlements, raid shipping vessels, or disrupt competitors’ trade networks. Privateers, acting with state approval, attacked rival ships carrying valuable cargo. These conflicts underscored how tightly economic and military interests converged in the age of exploration.

The Expanding Scale of Transatlantic Conflict

By the early seventeenth century, the Atlantic had become a contested geopolitical arena where European states continually sought advantage.

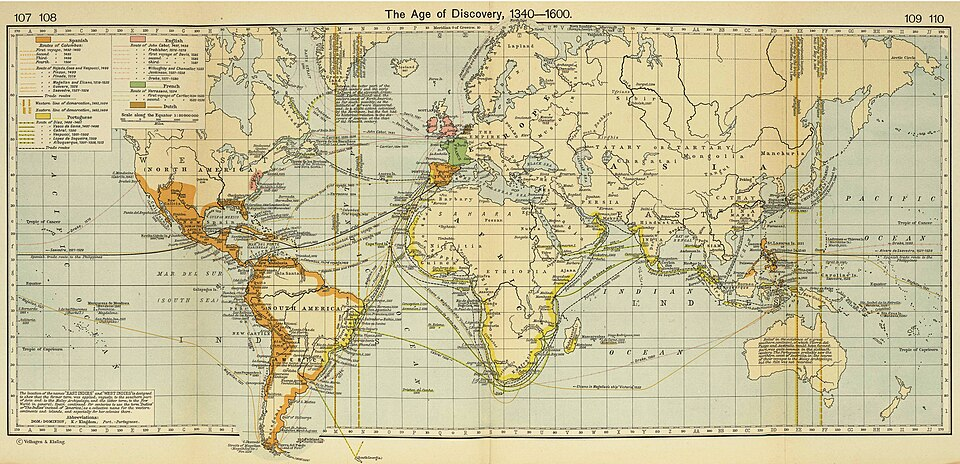

This historical map depicts European colonial empires and trade routes in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, including Spanish and Portuguese influence in the Americas. It emphasizes how several powers competed to control sea lanes and strategic ports. The map includes some global regions beyond the AP scope, but they help contextualize the global nature of imperial rivalry. Source.

The stakes of imperial competition expanded as:

New colonies offered access to lucrative commodities such as sugar, tobacco, and furs.

Rival powers built naval fleets to protect commerce and contest control of sea lanes.

Conflicts in Europe spill over into colonial warfare across the Americas.

European expansion in the Americas was therefore never a peaceful process of exploration; it was shaped fundamentally by constant economic and military rivalry. States acted aggressively to ensure that competitors did not gain the upper hand in wealth, territory, or strategic power.

FAQ

Mediterranean conflicts among Venice, Genoa, and the Ottoman Empire narrowed European access to Asian goods, increasing pressure to find alternative routes.

These constraints pushed emerging Atlantic kingdoms to compete aggressively for maritime innovation, state funding, and exploratory leadership.

The shift from Mediterranean to Atlantic competition set the stage for the intense rivalry seen during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries.

Smaller states such as England and France initially lacked the resources or political unity to compete with Iberian powers.

As their central governments strengthened and naval capabilities improved, they saw the wealth of Spain’s American empire and sought similar gains.

This delayed entry intensified rivalry because these states attempted to break Iberian monopolies through exploration, privateering, and colonisation.

Rivalry discouraged restraint; empires sought rapid territorial control to prevent competitors from claiming regions first.

This urgency often led to more aggressive military campaigns, forced alliances, and the strategic manipulation of Indigenous rivalries.

European powers also used Indigenous groups as proxies, arming them or leveraging alliances to undermine rival colonial ventures.

European powers developed systematic approaches to protect trade, including:

• Escorting treasure fleets

• Building fortified ports and coastal strongholds

• Expanding shipbuilding to maintain standing naval forces

These strategies allowed states to secure their trade networks while disrupting those of rival empires, intensifying geopolitical tension.

The papal support for Iberian territorial claims excluded northern states from lucrative opportunities in the Atlantic and Asia.

England, France, and the Dutch Republic rejected the legitimacy of Iberian monopolies, fostering a belief that challenging these claims was both justified and necessary.

This opposition laid the groundwork for privateering, piracy, and the eventual establishment of competing settlements across the Atlantic world.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one key reason why European states engaged in overseas exploration during the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Explain how this reason contributed to increased rivalry among European powers.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark – Identifies a valid reason (e.g., search for new trade routes, acquisition of precious metals, desire to outcompete rival states).

1 mark – Provides a brief explanation of how this reason encouraged competition (e.g., states competed to monopolise trade or gain wealth).

1 mark – Makes a clear connection to rivalry between specific European powers (e.g., Spain vs. Portugal, England vs. Spain).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how economic and military competition shaped the actions of European empires in the Americas between 1491 and 1607.

Mark Scheme:

1–2 marks – Describes relevant economic motives (e.g., securing access to resources, mercantilist goals, desire to dominate trade networks).

1–2 marks – Describes relevant military motives or actions (e.g., establishing fortified settlements, naval competition, use of soldiers and conquest).

1–2 marks – Provides analytical connections showing how these factors influenced imperial behaviour (e.g., accelerated colonisation, diplomatic conflicts, raids on rival shipping, increased state sponsorship).