AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use evidence from Period 1’s key concepts and historical developments to make a historically defensible claim.’

Crafting a historically defensible claim requires using accurate, relevant evidence from Period 1 to support a clear argument that reflects causation, continuity, and change over time.

Making a Historically Defensible Claim in Period 1

A historically defensible claim is an argument grounded in verifiable historical evidence and consistent with the broader interpretive frameworks historians use when analyzing the past. It must directly address a historical question, remain logically coherent, and draw on contextually appropriate information from Period 1 (1491–1607), including themes of contact, exchange, conflict, and adaptation among Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans.

Historically Defensible Claim: A historical argument that is factually accurate, supported by appropriate and specific evidence, and consistent with accepted historical interpretations.

A historically defensible claim does more than state an opinion; it must be substantiated by specific, relevant evidence from the period’s key developments, such as the Columbian Exchange, Spanish colonization, Indigenous resistance, and Atlantic world transformations.

This diagram shows the Columbian Exchange, highlighting the movement of plants, animals, diseases, and peoples between the Americas and Afro-Eurasia after 1492. It visually reinforces how exchanges in crops and livestock, as well as epidemic diseases, reshaped societies on both sides of the Atlantic. The image includes more specific examples of commodities and pathogens than your notes list, but all fall within the broader patterns emphasized for Period 1. Source.

Key Features of a Historically Defensible Claim

To meet AP U.S. History standards, a defensible claim should demonstrate several essential qualities that align with historical reasoning processes.

Clarity and Directness

A successful claim:

Responds precisely to the prompt.

Uses assertive language that takes a clear position.

Maintains internal consistency without contradiction.

Alignment with Historical Evidence

A claim must rely on verifiable patterns in the historical record. This includes evidence such as:

Demographic impacts of epidemics following European contact.

Social changes produced by new crops, animals, and technologies.

Economic developments like joint-stock companies and mineral extraction.

Cultural interactions, resistance, and adaptation among Native communities.

Evidence: Specific, relevant historical information—facts, events, developments, or primary/secondary sources—used to support an argument.

A historically defensible claim cannot rely on anachronisms, conjecture, or evidence outside the period under study.

After establishing the meaning of evidence, it becomes essential to consider how these details demonstrate causation or shaping forces within the period.

Consistency With Historical Interpretation

Defensible claims must align with what historians generally agree is accurate. While differing interpretations exist, an argument cannot contradict well-established facts such as:

The massive demographic collapse among Native Americans caused by European diseases.

The economic motivations driving Spanish and other European conquests.

The transformative effects of the Columbian Exchange on both hemispheres.

Integration of Period 1 Themes

The AP framework organizes history around several themes—politics, culture, geography, economy, migration, and power. A strong claim situates evidence within at least one of these themes to show broader significance.

Using Evidence From Key Concepts in Period 1

Because the specification requires using evidence from Period 1’s historical developments, students must understand the period’s most important forces and events. The following areas offer substantial evidence for grounding defensible claims.

Contact and Exchange in the Atlantic World

Students can draw on developments such as:

European exploration, driven by wealth, faith, and geopolitical competition.

Columbian Exchange, including new crops like maize and potatoes, the introduction of horses, and the spread of Old World diseases.

Population shifts and the rise of Atlantic economies shaped by resource extraction and coerced labor.

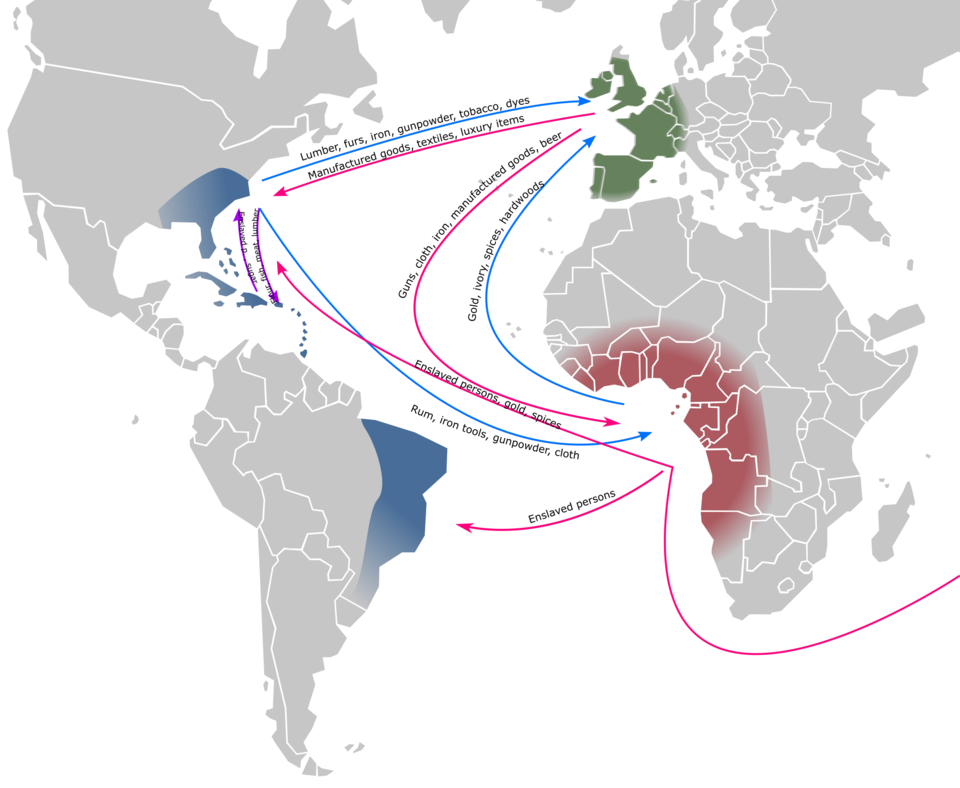

This economic map shows the major routes of the Atlantic triangular trade linking Europe, West Africa, and the Americas, including the forced transport of enslaved Africans. It helps students connect Period 1 beginnings of transatlantic commerce to broader patterns of coerced labor and plantation production. The map’s time span (1500–1800s) extends beyond Period 1, but visually captures the long-term development of exchange systems that originate in this era. Source.

Spanish Colonization and Labor Systems

Evidence from Spanish America provides rich support for claims related to economic transformation and social hierarchy. Relevant points include:

Use of encomienda systems to coerce Indigenous labor.

Importation of enslaved Africans to support plantation agriculture and mining.

Development of the casta system that structured colonial society.

The central role of mineral wealth, particularly silver, in shaping global trade networks.

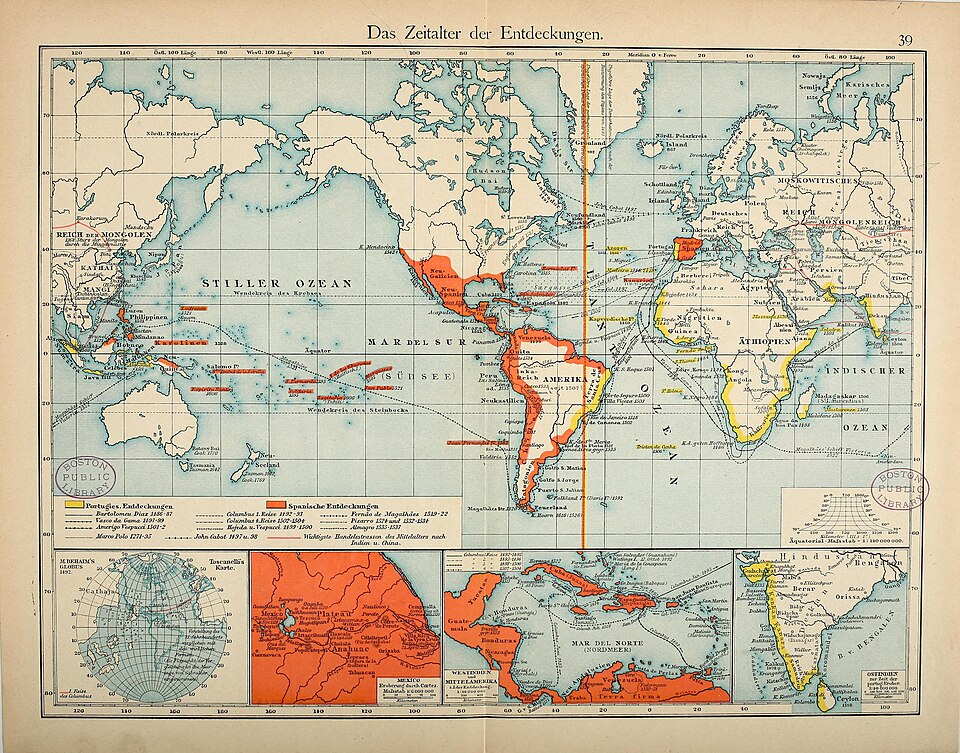

This historical map from Putzger’s school atlas shows the distribution of Spanish and Portuguese colonial territories in the 16th century. It reinforces the scale of Spanish control in the Americas that underpins arguments about encomienda, mineral extraction, and colonial social hierarchies. The map also includes Portuguese holdings outside the Americas, which go beyond the immediate AP U.S. History focus but still help situate Spanish America within a wider imperial world. Source.

Indigenous Adaptation and Resistance

Claims concerning Native American agency can be supported by evidence showing how Indigenous peoples responded to European encroachment:

Diplomatic strategies to preserve autonomy.

Armed resistance to European settlement.

Cultural adaptation and syncretic practices that blended European and Native beliefs.

Environmental manipulation and land-use practices that reflected longstanding ecological knowledge.

Structuring a Defensible Claim With Historical Reasoning

A historically defensible claim must rest on sound reasoning. AP U.S. History emphasizes three major reasoning processes: causation, comparison, and continuity and change over time. A strong argument draws on at least one of these processes.

Demonstrating Causation

To show cause and effect, a claim might argue how European arrival reshaped Indigenous societies. Possible causal links include:

Epidemics accelerating population decline.

New animals and crops reshaping settlement patterns.

Demand for labor spurring the growth of coercive systems.

Highlighting Continuity and Change

Claims may also emphasize how contact maintained some Indigenous traditions while transforming others, allowing students to trace developments from pre-contact societies through early colonial encounters.

Using Comparison to Strengthen Claims

Comparative reasoning helps position a claim within broader historical patterns:

Comparing Spanish, French, and English motivations.

Contrasting Native societies in different regions.

Examining varying degrees of cooperation and conflict across early encounters.

Presenting a Historically Defensible Claim

To craft a strong claim for AP U.S. History writing tasks, students should structure their argument using the following components:

A precise answer to the prompt framed as a clear argument.

Evidence from Period 1 key concepts that directly supports the claim.

Explanation of how and why the evidence validates the argument.

Use of historical reasoning to connect examples to a broader pattern.

Avoidance of unsupported generalizations, anachronisms, or claims that contradict established historical knowledge.

Writing a historically defensible claim requires skillful integration of evidence, reasoning, and thematic understanding from Period 1. Through careful selection of evidence and clear argumentation, students demonstrate mastery of early American history and the analytical rigor expected at the AP level.

FAQ

A historically defensible claim is the core argument that must be supported by accurate and relevant historical evidence. It is the minimum requirement for making a valid historical assertion.

A thesis statement, however, embeds that claim within a broader argument structure. It typically previews the reasoning or categories that will be used to support the claim, linking evidence to a wider analytical framework.

In short, the defensible claim is the foundation, while the thesis is the more developed, blueprint-like version of that argument.

Evidence that shows clear, measurable change or well-documented effects strengthens claims most reliably.

Useful types include:

Demographic data linked to epidemics.

Agricultural changes resulting from the transfer of crops or animals.

Economic records revealing extraction, trade patterns, or labour systems.

Accounts from European or Indigenous perspectives illustrating cultural misunderstanding or adaptation.

The key is choosing evidence that directly reinforces the argument rather than merely describing events.

Historical reasoning helps move from description to analysis by showing why evidence matters.

For example:

Causation clarifies how one development triggered another.

Continuity and change highlights long-term patterns or breaks across time.

Comparison shows similarities and differences that reveal broader significance.

Integrating these processes helps demonstrate the relationship between the evidence and the claim, making the argument more rigorous and defensible.

Students often fall into predictable pitfalls such as:

Using evidence from later periods or outside the Atlantic world.

Relying on vague generalisations instead of specific developments.

Making claims that contradict widely accepted historical facts.

Describing events without making an actual argument.

A defensible claim requires precision. It must draw on the right timeframe, include specific detail, and take a clear position based on credible evidence.

A simple self-check can help validate a claim:

Can you provide at least two accurate and relevant pieces of evidence from Period 1 to support it?

Does the claim align with widely accepted scholarship rather than speculation?

Is it directly responsive to the prompt, without drifting into unrelated topics?

Can you explain how your evidence proves the point using reasoning such as causation or change?

If the answer to any of these is no, the claim needs refinement before writing further.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain what makes a historical claim “defensible” when analysing developments in Period 1 (1491–1607).

Mark scheme

1 mark: Identifies that a defensible claim must be supported by evidence.

1 mark: States that the evidence must be accurate, relevant, and drawn from Period 1.

1 mark: Explains that the claim must be logically consistent and align with accepted historical interpretations.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using specific evidence from Period 1 (1491–1607), develop a historically defensible claim about the impact of early European–Native American contact. Ensure your argument reflects a recognised historical reasoning process such as causation, comparison, or continuity and change.

Mark scheme

1 mark: States a clear and defensible claim about the impact of early contact.

1 mark: Provides at least one accurate piece of relevant evidence from Period 1.

1 mark: Provides a second accurate and relevant piece of evidence from Period 1.

1 mark: Explains how the evidence supports the claim.

1 mark: Uses at least one historical reasoning process (e.g., demonstrating cause and effect, or identifying continuity/change).

1 mark: Maintains a coherent, historically accurate argument consistent with established interpretations.