AP Syllabus focus:

‘Ongoing trade increased the flow of goods in and out of American Indian communities, driving cultural and economic changes and spreading epidemic diseases that caused major demographic shifts.’

Transatlantic trade transformed Indigenous societies by reshaping material culture, spreading devastating diseases, and altering political and economic relationships amid expanding European competition throughout North America.

Trade Networks and Material Exchange

Expanding Indigenous Access to European Goods

The rise of Atlantic trade dramatically increased the availability of European manufactured goods in Indigenous communities. American Indians strategically incorporated these new materials into existing economic and social structures.

Metal tools such as axes, knives, and kettles enhanced hunting and processing efficiency.

Firearms, though unevenly distributed, reshaped power balances between Indigenous nations.

Cloth, beads, and decorative items became woven into cultural expression and diplomacy.

Material Culture: The physical objects, technologies, and goods that shape the daily life and traditions of a society.

Indigenous peoples did not simply adopt European goods wholesale; they adapted them to fit established cultural frameworks. For example, replacing stone arrowheads with iron ones improved durability but maintained traditional hunting methods. Access to European textiles allowed for new clothing styles without erasing Indigenous identity.

Trade as a Driver of Intertribal Competition

Growing access to trade goods intensified rivalries among Indigenous nations competing for favorable relationships with European powers.

Control of fur-rich territories became increasingly valuable.

Nations sought exclusive trading partnerships to secure stable supplies of weapons and goods.

Competition sometimes created cycles of displacement as groups migrated, fought, or negotiated to preserve access to trade.

These exchanges strengthened some nations—such as the Iroquois Confederacy—while undermining others whose territories or alliances weakened under mounting pressures.

Champlain Trading with the Indians illustrates Indigenous people exchanging furs for European beads, tools, and other manufactured goods. The scene highlights how Native communities incorporated foreign items into existing cultural and economic systems. Although set in French Canada, it reflects broader patterns of Indigenous–European trade across northeastern North America. Source.

Cultural Change and Indigenous Adaptation

Transformation of Daily Life

European goods influenced how Indigenous peoples conducted labor, warfare, and diplomacy.

Metal axes and kettles reduced time spent on traditional toolmaking, freeing labor for hunting or trade.

Firearms required new military strategies and maintenance skills and increased the stakes of armed conflict.

Alcohol, introduced through trade, generated social disruption and altered some diplomatic interactions with Europeans.

Indigenous societies selectively incorporated new materials, but these shifts often brought broader changes to leadership structures, gender roles, and traditional economies.

Shifting Political Relationships

Trade fostered complex alliances between Indigenous nations and European powers.

Diplomatic gift-giving relied increasingly on European-made goods.

Leaders who controlled trade routes gained political authority.

Intermarriage between European traders and Indigenous women strengthened diplomatic ties, especially in French and Dutch spheres.

These new political dynamics created opportunities for Indigenous agency but also made communities vulnerable to changing European priorities.

Disease and Demographic Change

Epidemic Disease as a Consequence of Trade

The movement of people and goods across the Atlantic and throughout inland trade routes facilitated the spread of epidemic diseases, including smallpox, measles, and influenza.

Many Indigenous communities experienced catastrophic population loss, often exceeding 70–90 percent.

Diseases spread faster than European settlement, reaching communities that had never directly encountered Europeans.

Repeated epidemic cycles eroded social structures, created leadership vacuums, and weakened resistance to colonial encroachment.

Epidemic: The rapid spread of an infectious disease within a population, causing unusually high rates of illness and mortality.

These demographic shocks amplified the effects of trade. Communities that had lost significant populations struggled to maintain agricultural production, protect territory, or sustain labor-intensive cultural practices.

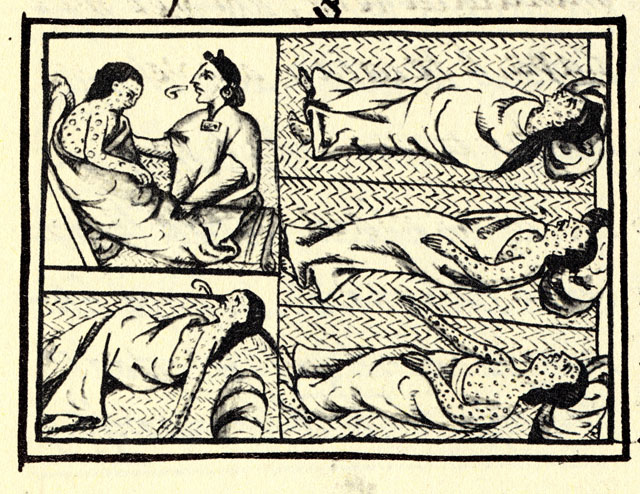

This panel from the Florentine Codex depicts Indigenous people suffering from smallpox, their bodies covered in lesions as a healer tends to the sick. It conveys the devastation and social breakdown that epidemic disease brought to Native communities after contact. Although drawn in central Mexico, it reflects epidemiological patterns impacting Indigenous societies throughout North America. Source.

Social and Political Consequences of Population Collapse

Disease altered Indigenous political landscapes on a vast scale.

Depopulated villages merged for survival, creating new political alliances.

Some nations shifted territories to escape contaminated regions or hostile neighbors.

European powers exploited weakened Indigenous nations to extract land concessions or secure labor and trade advantages.

Surviving communities often restructured gender roles and kinship systems, particularly when disproportionate mortality affected certain age groups or social classes.

Long-Term Economic Transformations

Dependency and Market Integration

As Indigenous groups exchanged furs and other goods for European items, they increasingly interacted with a broader Atlantic economy. Over time, this created forms of dependency:

European traders often demanded large quantities of pelts, pushing hunters deeper into forests.

Overhunting strained animal populations, making communities more reliant on trade to replace lost local resources.

Seasonal cycles shifted as hunting for export overtook subsistence patterns.

These economic pressures contributed to long-term environmental changes as beaver and other fur-bearing species declined in some areas.

Resilience and Cultural Persistence

Despite enormous challenges, many Indigenous societies preserved and adapted key cultural traditions.

Ceremonies, languages, and social structures persisted even as communities integrated European goods.

Some nations strategically manipulated trade relationships to maintain autonomy.

Cultural blending produced new hybrid practices, particularly in clothing, diplomacy, and material culture.

Indigenous resilience shaped the evolution of North American societies and ensured that cultural transformation did not equate to cultural disappearance.

Interconnected Change Across the Continent

Trade brought goods, disease, and profound transformation, linking Indigenous communities to a rapidly globalizing world. As the flow of goods increased, so too did the movement of people, pathogens, and ideas, creating dramatic and often tragic demographic shifts. Yet through adaptation, diplomacy, and cultural endurance, Indigenous nations continued to shape the North American landscape even amid the disruptive forces of Atlantic commerce.

FAQ

Many Indigenous groups structured trade through diplomatic rituals, gift-giving, and ceremonial meetings, which established expectations of reciprocity and mutual obligation. These practices often constrained European traders who relied heavily on Indigenous knowledge and cooperation.

Indigenous nations also strategically switched trading partners when goods declined in quality or when rival Europeans offered better terms. Control of key river routes or portage points allowed some nations to impose conditions or fees on European traders.

Disease impact varied due to differences in population density, mobility, and prior exposure. Sedentary agricultural communities typically suffered higher mortality because infections spread faster in concentrated settlements.

Geographic isolation sometimes delayed outbreaks, but when diseases eventually arrived, communities with no immunity experienced catastrophic loss. Groups deeply embedded in long-distance trade networks faced repeated epidemics due to frequent contact with infected travellers or goods.

The fur trade increased the demand for male hunting labour, often shifting men’s time from farming to trapping. Women’s roles simultaneously expanded in areas such as processing pelts, constructing trade-ready goods, and managing domestic production disrupted by European imports.

Some communities saw changes in marriage alliances, as European traders relied on unions with Indigenous women to access diplomatic networks and local knowledge.

Alcohol became a commodity in some trade relationships, and its use could disrupt social norms and undermine leadership authority. It created tensions within communities as individuals’ behaviour shifted under its influence.

Some nations attempted to regulate or restrict alcohol distribution through formal councils. Others used spiritual practices to address its effects, incorporating rituals aimed at restoring balance and social cohesion.

Intensified hunting for export led to overharvesting of beaver, otter, and other fur-bearing animals, altering wetlands and forest ecosystems. Loss of beaver dams, for example, changed water flow patterns and affected fish populations.

Communities that relied heavily on depleted species often had to migrate or renegotiate trade terms. Environmental strain also reshaped territorial boundaries as groups sought new resource areas or defended remaining stocks.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one specific way in which increased trade with Europeans altered the material culture of an Indigenous community in North America during the seventeenth or eighteenth century.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for correctly identifying a European good or technological item adopted by Indigenous peoples (e.g., metal tools, firearms, textiles, beads).

• 1 mark for explaining how this good altered Indigenous material culture (e.g., improving efficiency, changing hunting practices, integrating into clothing or ceremonial use).

• 1 mark for linking this change to broader cultural or economic adaptation (e.g., enhanced trade status, altered warfare, modifications to daily life).

Full marks require a clear, specific example and a brief explanation of its impact.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how the growth of trade networks between Indigenous peoples and Europeans contributed both to cultural change and to demographic decline among Indigenous societies between 1607 and 1754.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1–2 marks for describing how European–Indigenous trade networks expanded (e.g., increased circulation of goods, growing reliance on fur exports, alliances formed around trade access).

• 1–2 marks for explaining cultural changes arising from trade (e.g., adoption of firearms altering warfare, metal tools changing labour patterns, political shifts due to control of trade routes).

• 1–2 marks for explaining demographic decline tied to trade and contact (e.g., spread of smallpox and other diseases along trade routes, population loss weakening communities).

Full marks require clear explanation of both cultural change and demographic decline, rooted in accurate historical examples or processes.