AP Syllabus focus:

‘Britain tried to organize its North American colonies into a hierarchical imperial system to pursue mercantilist aims, but conflicts with colonists and American Indians made enforcement uneven.’

British mercantilism shaped economic policy in the colonies, encouraging regulated trade and imperial oversight, yet colonists’ resistance and frontier conflicts often disrupted attempts at uniform control.

Mercantilism as an Imperial Economic System

British leaders in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries embraced mercantilism, an economic philosophy that viewed global wealth as finite and sought to maximize national power through controlled trade and resource extraction.

Mercantilism: An economic theory asserting that nations grow wealthier and stronger by maintaining a favorable balance of trade and controlling colonial markets and resources.

British policymakers believed colonies existed primarily to enrich the metropole, meaning the imperial center. These ideas shaped nearly every governmental, economic, and commercial decision Britain made regarding North America.

Core Goals of British Mercantilist Policy

British imperial strategists tried to build a tightly integrated Atlantic system linking the colonies to English commercial priorities.

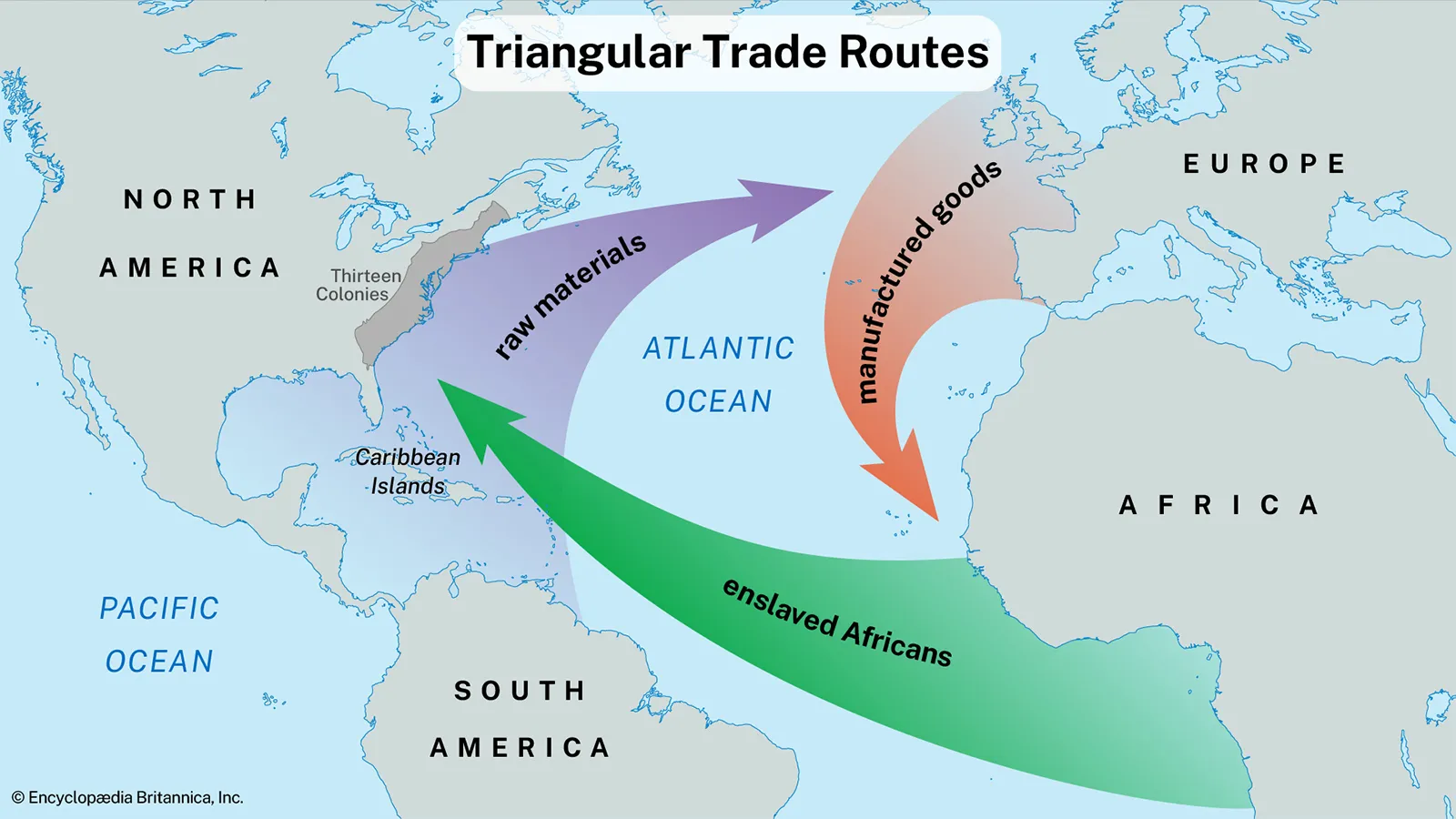

A simplified map of Atlantic triangular trade routes, showing flows of manufactured goods from Europe, enslaved Africans from West Africa, and raw materials from the Americas. The diagram illustrates how imperial governments used controlled trade routes to tie colonial production into metropolitan priorities. Although it emphasizes the slave trade, it also helps students visualize the broader mercantilist goal of directing colonial wealth through a regulated Atlantic network. Source.

Their chief goals included:

Securing raw materials to reduce reliance on foreign imports.

Guaranteeing markets for English manufactured goods.

Regulating colonial trade to keep profits within the empire.

Expanding the merchant marine to ensure the empire controlled shipping.

These policies aimed to elevate England’s global power relative to rivals such as France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic.

Imperial Control Through Navigation Acts

The primary mechanism Britain used to implement mercantilist objectives was the Navigation Acts, a series of statutes beginning in the mid-1600s designed to regulate colonial commerce.

Major Features of the Navigation Acts

British laws required:

Colonial goods to be transported on English or colonial ships.

Certain “enumerated goods” (such as tobacco and sugar) to be exported only to England or another English colony.

Most imported European goods destined for the colonies to pass through England first, paying customs duties.

These measures strengthened English shipping industries and ensured that customs revenue and commercial advantages flowed to the empire.

Enforcement Challenges and Colonial Responses

Although intended to create a strict hierarchical imperial system, enforcement in North America remained inconsistent. Distance, limited personnel, and widespread smuggling undermined the legislation. Many colonists ignored restrictions when profitable alternatives existed, trading with French, Dutch, or Spanish ports despite legal prohibitions.

A seventeenth-century engraving of the ships Sampson, Salvadore, and St. George, Dutch vessels disguised as Spanish ships to evade the 1651 Navigation Act. The image highlights how merchants and rival European powers circumvented English trade regulations central to the mercantilist system. Although shown in a European maritime context, it effectively illustrates the enforcement challenges that weakened British imperial control. Source.

Conflicts with Colonists

Imperial controls aimed to reinforce Britain’s authority, but they also generated resentment among colonists who valued economic flexibility and local autonomy. Reactions varied by region, depending on economic structure, leadership, and proximity to imperial officials.

Sources of Colonial Frustration

Several key tensions contributed to dissatisfaction with mercantilist regulation:

Economic limits: Restrictions on trade reduced profits for merchants and planters accustomed to a broad Atlantic network.

Political friction: Royal governors attempted to enforce statutes, but colonial assemblies resisted what they saw as encroachments on self-government.

Smuggling prosecutions: Efforts to curb illicit trade—occasionally through vice-admiralty courts without juries—heightened fears of unchecked imperial power.

These tensions strengthened emerging beliefs in local economic rights and challenged Britain’s confidence in its ability to shape colonial behavior.

American Indian Relations and Imperial Control

Conflicts with Indigenous groups complicated Britain’s efforts to organize the colonies into a coherent system.

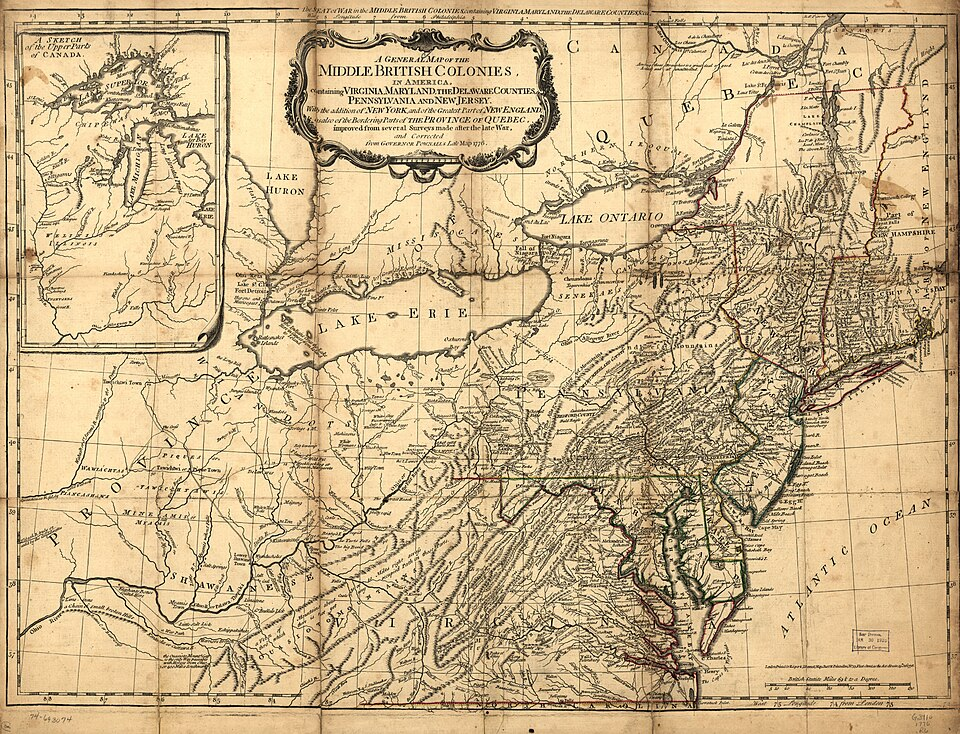

An eighteenth-century map of the middle British colonies, including major ports, rivers, and inland frontier regions. These spatial features shaped colonial trade, settlement, and the contested borderlands that limited the reach of British mercantilist policy. The map includes additional territorial details, but they provide helpful context for understanding imperial control and resistance. Source.

Impact of Frontier Conflict

Violence along the frontier—such as clashes in the Ohio Valley or disputes over land in the Southeast—strained imperial resources. Costs of defense encouraged Britain to demand greater colonial obedience, including stricter trade enforcement and increased revenue extraction. Colonists frequently interpreted these moves as economic oppression rather than shared security measures.

Uneven Enforcement Across the Empire

Britain’s ambitions for a tightly regulated commercial empire met the reality of fragmented colonial societies and limited administrative capacity. Enforcement patterns ranged from lax oversight in New England to more assertive monitoring in key ports like Charleston or Boston.

Reasons for Uneven Imperial Control

Several factors prevented consistent application of mercantilist policy:

Geographic distance, which slowed communication and weakened supervision.

Local political structures, including strong assemblies resistant to royal authority.

Economic diversity, causing colonies to experience imperial regulations differently based on local industries.

Competing priorities, such as wars in Europe, which diverted attention from colonial management.

These dynamics ensured that the mercantilist system remained only partially successful, shaping the economic foundation of the empire but failing to fully discipline colonial trade.

Long-Term Significance

Mercantilist regulation and inconsistent enforcement left a deep imprint on colonial political culture. Colonists learned to navigate, negotiate, and often defy imperial constraints. The resulting pattern of tension, resistance, and partial compliance would later influence debates over sovereignty, trade, and taxation leading up to the American Revolution.

FAQ

British enforcement gradually shifted from relying on local colonial officials to deploying crown-appointed customs officers who answered directly to London.

They used measures such as increasing inspections of ships, requiring more detailed cargo manifests, and collaborating with the Royal Navy to patrol busy Atlantic routes.

However, enforcement remained inconsistent because colonial juries often sided with local merchants, prompting Britain to experiment with vice-admiralty courts that removed juries from smuggling cases.

Merchants developed sophisticated networks to bypass imperial regulations, often partnering with Dutch, French, and Spanish traders.

They used tactics such as:

Off-loading goods at remote coves to avoid customs officials

Re-labelling cargo to disguise origins

Using intermediaries in the Caribbean to obscure trade routes

These practices were driven by the desire for better prices and wider markets than Britain’s controlled system allowed.

New England had a diversified economy built on shipping, fishing, and small-scale manufacturing, making merchants less dependent on British demand for staple crops.

The region’s numerous small ports and rocky coastline offered ideal conditions for smuggling and private trade with rival European colonies.

In addition, New Englanders often viewed imperial trade restrictions as threats to their autonomy, leading to local juries resisting prosecutions of accused smugglers.

Major conflicts such as King William’s War and the War of the Spanish Succession diverted Britain’s military and financial resources away from colonial supervision.

With the Royal Navy heavily committed to European theatres, fewer ships were available to patrol colonial waters and inspect merchant vessels.

Colonial governments often used wartime conditions to expand illicit trade, arguing that local needs outweighed strict imperial compliance.

Colonies were not unified in their economic interests. Coastal merchants, back-country settlers, and plantation elites often held different views on imperial regulation.

These divisions made coherent resistance unlikely but also prevented Britain from applying uniform policies, as officials frequently adapted rules to local circumstances.

Factional politics within assemblies further complicated enforcement, with some leaders courting popular support by resisting crown efforts to tighten economic controls.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Navigation Acts reflected British mercantilist aims.

Question 1

1 mark – Identifies a valid mercantilist aim reflected in the Navigation Acts (e.g., controlling colonial trade, ensuring profits flowed to Britain).

2 marks – Provides a clear explanation of how the Navigation Acts achieved this aim (e.g., requiring enumerated goods to be shipped only to Britain).

3 marks – Offers a well-developed explanation showing accurate historical knowledge and a direct link to British mercantilist ideology (e.g., how restricting shipping to English vessels strengthened the merchant marine and ensured economic benefits remained within the empire).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which conflicts with colonists and Indigenous peoples limited Britain’s ability to enforce mercantilist policies in North America between 1650 and 1750.

Question 2

4 marks – Gives a general explanation of how such conflicts affected enforcement, with at least one specific example (e.g., smuggling, frontier violence).

5 marks – Provides a more analytical response, addressing both colonists and Indigenous peoples, and explains how these conflicts weakened imperial control.

6 marks – Presents a well-structured argument evaluating the relative significance of different types of conflict, uses specific evidence (e.g., frontier wars, resistance to vice-admiralty courts), and directly assesses the degree to which enforcement was limited.