AP Syllabus focus:

‘As chattel slavery expanded, colonial laws created a strict racial system that restricted interracial relationships and made children of enslaved mothers legally Black and enslaved for life.’

Chattel slavery in the British colonies evolved into a rigid racial hierarchy that defined status, rights, and identity, shaping colonial society and institutionalizing racial inequality for generations.

The Legal Foundations of Chattel Slavery

As the labor demands of plantation agriculture grew, British colonial governments codified chattel slavery, making enslaved Africans and their descendants legally considered property rather than persons. This system was designed to ensure a permanent, inheritable labor force and to prevent challenges to colonial economic structures.

The Emergence of a Race-Based Legal System

During the late 17th century, colonial assemblies increasingly passed laws that connected slavery to racial identity. These statutes clarified ownership rights, restricted freedoms, and solidified distinctions between Europeans, Africans, and Indigenous peoples. As this framework developed, racial difference became the primary justification for enslavement, displacing earlier economic or religious rationales.

The Principle of Hereditary Slavery

A crucial feature of the system was the legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem, introduced in Virginia in 1662. It declared that a child’s legal status followed that of the mother.

Partus sequitur ventrem: A legal principle establishing that children inherited the enslaved status of their mothers, ensuring slavery’s perpetual reproduction.

This doctrine overturned English common law, which typically traced status through the father, and it enabled plantation owners to expand enslaved populations without relying solely on the transatlantic slave trade.

This print portrays a woman, likely enslaved, holding a child, emphasizing the vulnerability of families under hereditary slavery. Colonial law defined both mother and child as property, shaping the lived realities of Black families. Although not tied to a specific colony, the image illustrates the human impact of racialized inheritance laws. Source.

A legal environment built on hereditary status transformed slavery from a labor system into a racial caste system. These developments aligned with the AP focus on how children of enslaved mothers became legally Black and enslaved for life, reinforcing the racial hierarchy.

Restricting Interracial Relationships and Social Mobility

To protect the emerging racial order, colonial governments enacted laws aimed at preventing or punishing interracial relationships, especially those between Black men and white women. Such laws sought to guard the perceived purity of the white population and to eliminate potential claims to freedom based on paternal lineage.

Laws Limiting Sexual and Marital Relationships

Colonial statutes imposed harsh penalties for interracial marriage or cohabitation. These measures strengthened racial divisions by marking interracial intimacy as socially threatening and legally dangerous. They also reinforced the idea that whiteness carried legal privileges unavailable to others.

Social and Cultural Enforcement

While laws created the structure, social customs helped enforce it. White colonists increasingly equated whiteness with freedom, Christianity, and political rights, while Blackness became associated with enslavement, heathenism, and inferiority. Such distinctions justified the expansive control exercised over enslaved people and limited opportunities for free people of African descent.

Codifying Racial Difference Through Slave Codes

Slave codes varied by colony but consistently reinforced the racial hierarchy. They aimed to regulate behavior, suppress potential rebellions, and cement white authority. These legal codes contributed directly to what the AP specification describes as a strict racial system.

Core Components of Slave Codes

• Movement restrictions: Enslaved people were banned from traveling without written authorization.

• Prohibitions on assembly: Gathering in groups was limited to prevent collaboration or resistance.

• Limitations on literacy: Laws forbade teaching enslaved people to read or write, preventing self-advocacy and political consciousness.

• Differential punishments: Enslaved Africans received harsher penalties than whites for similar offenses.

• Militia oversight: White colonists were obligated to participate in patrols that monitored and controlled enslaved populations.

These codes institutionalized surveillance and coercion, ensuring that the racial hierarchy remained embedded in everyday life.

The Role of Religion in Racial Hierarchy

Early in the colonial period, some enslaved Africans converted to Christianity and attempted to claim freedom based on shared religious identity with Europeans. In response, colonies passed laws declaring that conversion did not alter enslaved status, severing religious affiliation from legal rights. This shift reinforced race—not faith—as the defining factor of social position.

Enslaved Identity, Racial Categories, and Social Stratification

Colonial societies developed increasingly precise racial classifications, often using terms like mulatto, quadroon, and octoroon to categorize mixed ancestry. These labels were not merely descriptive; they held legal significance, determining rights, restrictions, and social expectations. Such categories helped maintain the boundary between whiteness and Blackness, even when individuals might appear racially ambiguous.

The Growth of a Free Black Population

Despite the restrictive laws, a small population of free people of African descent emerged through manumission, self-purchase, or military service. However, even freedom did not erase racial barriers. Free Black people still faced limitations on property ownership, movement, inheritance, and political participation. Their constrained rights underscored that the racial hierarchy transcended enslaved status.

Economic Motivations Behind Racial Hierarchy

Plantation agriculture—especially tobacco, rice, and later indigo—depended on labor-intensive cultivation. A racially defined system ensured planters a controlled, inheritable workforce. By tying slavery to race, colonial elites minimized legal challenges to ownership and justified the system as natural, permanent, and divinely sanctioned.

This economic foundation helps explain why racial hierarchy became so deeply entrenched: it protected wealth, stabilized labor supplies, and legitimized social inequality across generations.

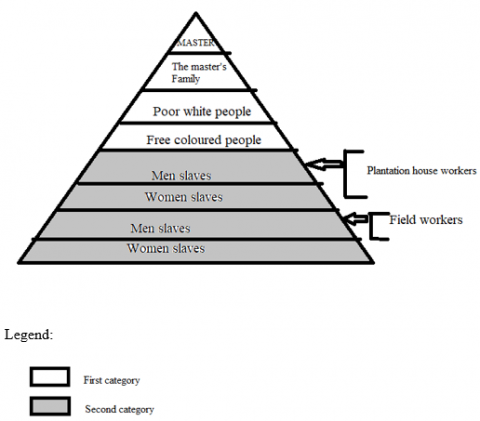

This diagram displays a plantation society structured as a social pyramid, with white planters at the top and enslaved Africans at the base. It visualizes how race and legal status created a rigid hierarchy in slave societies. Although drawn from a Caribbean context, it reflects the same racialized social order that developed in the British mainland colonies. Source.

FAQ

Colonial courts increasingly argued that religious conversion did not alter a person’s legal condition, claiming that enslavement was a civil, not spiritual, matter. This allowed lawmakers to separate Christian identity from legal freedom and ensured that enslaved Africans could not use baptism as a path to emancipation.

This shift normalised the idea that racial identity, rather than belief or behaviour, defined a person’s rights and social position.

Gender shaped how racialised laws operated. Enslaved women were central to the legal and economic reproduction of slavery because their children automatically inherited enslaved status.

Meanwhile, interracial relationships involving white men were often tolerated or overlooked, while those involving white women were heavily penalised. This imbalance reinforced patriarchal control and protected white male authority within the racial hierarchy.

Punishments for enslaved Africans were often deliberately public and physically severe, intended not only to discipline but to demonstrate white authority.

In contrast, white colonists committing similar offences faced lighter penalties.

• This disparity communicated that racial identity determined legal protection.

• It also discouraged solidarity between poor whites and enslaved Africans by making shared resistance costly.

Yes. Free Black individuals sometimes purchased relatives’ freedom, brought lawsuits, or accumulated property despite legal restrictions.

Their modest successes occasionally worried colonial authorities, who feared that a prosperous free Black class might undermine the justification for enslavement. This tension led some colonies to tighten laws limiting movement, assembly, and inheritance for free Black residents.

Indentured servants eventually gained freedom and could compete economically, demand land, or resist elite control. Their limited-term status made them unreliable for long-term plantation investment.

Hereditary slavery, however:

• guaranteed a permanent labour force,

• prevented labourers from entering the landholding class, and

• tied workforce growth to reproduction rather than immigration.

This made plantation economies more predictable and profitable for elite landowners.

Practice Questions

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the ways in which colonial laws restricting interracial relationships and codifying enslaved status shaped social and economic structures in the British colonies between the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Mark scheme for Question 2

• 1 mark for describing laws restricting interracial marriage or sexual relationships.

• 1 mark for explaining that these laws reinforced distinctions between white and Black populations.

• 1 mark for describing laws that codified enslaved status, such as hereditary enslavement or slave codes.

• 1 mark for explaining how these laws ensured a stable and legally controlled labour force.

• 1 mark for linking legal restrictions to the broader economic needs of plantation agriculture.

• 1 mark for analysing how these measures entrenched a racial hierarchy that structured colonial society.

Maximum: 6 marks.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how the legal principle of partus sequitur ventrem contributed to the development of a rigid racial hierarchy in the British colonies.

Mark scheme for Question 1

• 1 mark for identifying the principle as determining a child’s status through the mother.

• 1 mark for explaining that this made slavery inheritable and permanent.

• 1 mark for linking this inheritance rule to the creation or reinforcement of a race-based social hierarchy.

Maximum: 3 marks.