AP Syllabus focus:

‘Enslaved Africans used overt and covert resistance while maintaining family and gender systems, culture, and religion in the face of slavery’s dehumanizing conditions.’

Enslaved Africans in early British America navigated a violent, coercive system by resisting bondage in varied ways while preserving cultural traditions, kinship ties, and spiritual practices that sustained community life.

Resistance and Cultural Survival under Slavery

Enslaved people in the English colonies confronted a system designed to control their labor, restrict their movement, and deny their humanity. Yet throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they consistently challenged enslavement through overt resistance, covert strategies, and deliberate efforts to maintain cultural, familial, and religious traditions. These acts—ranging from rebellion to subtle daily defiance—highlight resilience within an oppressive colonial order built upon chattel slavery, defined as the legal treatment of enslaved individuals as property.

Chattel Slavery: A system in which people are legally treated as property who can be bought, sold, and inherited, with status passed through the mother.

Despite harsh conditions, enslaved Africans created cultural practices that blended African traditions with the realities of colonial life. Their strategies of endurance and resistance shaped the development of African American identity across British North America.

Overt and Covert Forms of Resistance

Overt Resistance

Overt resistance refers to visible, intentional acts of defiance. Although large-scale revolts were relatively rare due to constant surveillance and severe punishments, they were deeply significant.

Organized uprisings, such as small plantation rebellions, challenged slaveholders directly and attempted to secure freedom through force.

Conspiracies revealed the willingness of enslaved communities to coordinate plans despite extreme risks.

Running away, either temporarily or permanently, was one of the most common forms of overt resistance, disrupting labor systems and asserting autonomy.

Covert or Everyday Resistance

Far more common than open rebellion were subtle strategies that undermined plantation discipline and asserted personal agency.

Work slowdowns, feigned illness, or intentional mistakes reduced productivity and contested slaveholders’ control.

Sabotage, including damaging tools or manipulating work routines, weakened the economic structure of slavery.

Cultural and linguistic retention, such as speaking African languages or preserving naming traditions, served as powerful symbolic resistance.

These covert actions created daily friction in the slave system and allowed enslaved people to exercise limited control over their lives.

Family and Gender Systems as Foundations of Community

Kinship Networks

Enslaved Africans built kinship networks that often extended beyond biological ties. These relationships helped maintain continuity in the face of constant threat from sale or separation.

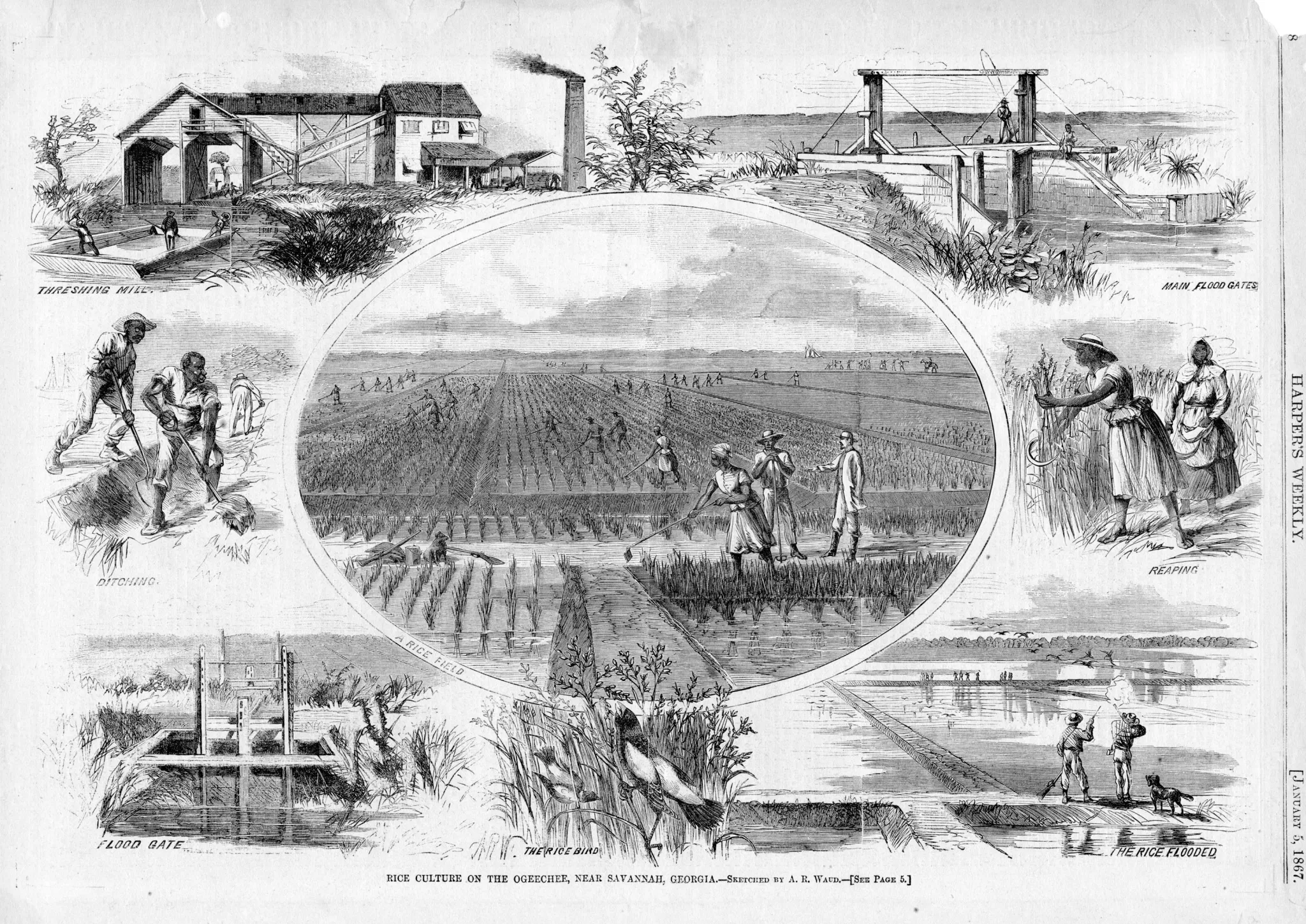

An enslaved family picks cotton near Savannah, illustrating how adults and children worked together under the demands of plantation agriculture. The image highlights the central role of family and kinship networks in sustaining community life despite the violence and instability of slavery. It includes additional visual detail about cotton production that goes beyond the specific focus on resistance but remains closely connected to enslaved people’s daily experiences. Source.

Fictive kin—nonbiological family ties—provided emotional support and social stability.

Naming customs, frequently drawing on African heritage, reinforced identity and connection across generations.

Child-rearing practices emphasized collective responsibility, ensuring cultural transmission.

Gender Roles and Labor Expectations

Gender roles within enslaved communities differed from those in European society because plantation demands required both men and women to perform arduous labor.

Enslaved women worked in the fields alongside men while also sustaining domestic labor, childrearing, and community rituals.

Enslaved men navigated expectations of physical labor and communal leadership even within restricted conditions.

Shared labor experiences fostered solidarity and reinforced community cohesion.

These gender and familial systems enabled enslaved people to preserve cultures and create a sense of belonging despite the instability imposed by slavery.

Religion, Culture, and Community Survival

African Spiritual Traditions and Syncretism

Enslaved Africans brought with them diverse religious practices—Islamic traditions, West African spiritual systems, and communal rituals. Over time, these blended with Christian teachings introduced by missionaries and slaveholders.

Syncretism, the mixing of African and Christian beliefs, allowed enslaved people to create spiritually meaningful practices that affirmed identity.

Rhythmic worship, call-and-response singing, and dance linked African aesthetics to new contexts.

Invisible churches—secret religious gatherings—provided safe spaces for collective worship outside white supervision.

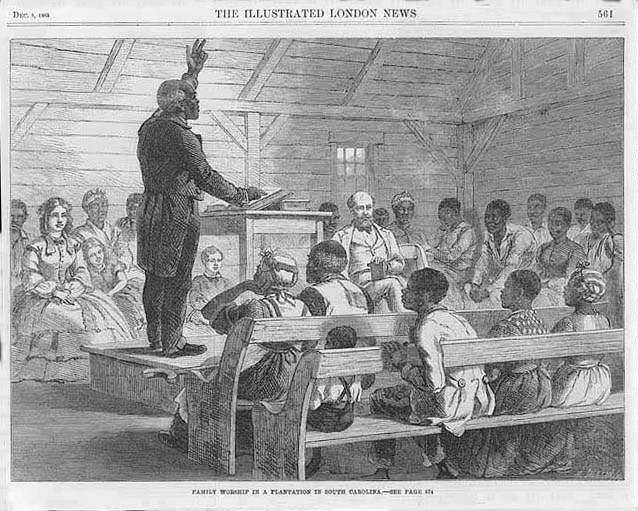

An illustration of enslaved people gathered for worship on a plantation shows a Black preacher addressing a community in a simple meeting space. The scene reflects how religious gatherings blended African traditions with Christian teachings and offered emotional support, hope, and a measure of autonomy. Additional interior details appear that extend beyond syllabus requirements but help visualize the environment of enslaved worship. Source.

Music, Language, and Cultural Expression

Music, storytelling, and language retention were central to cultural survival.

Oral traditions preserved historical memory and communicated moral lessons.

Music and spirituals functioned as tools for expression, resistance, and coded communication.

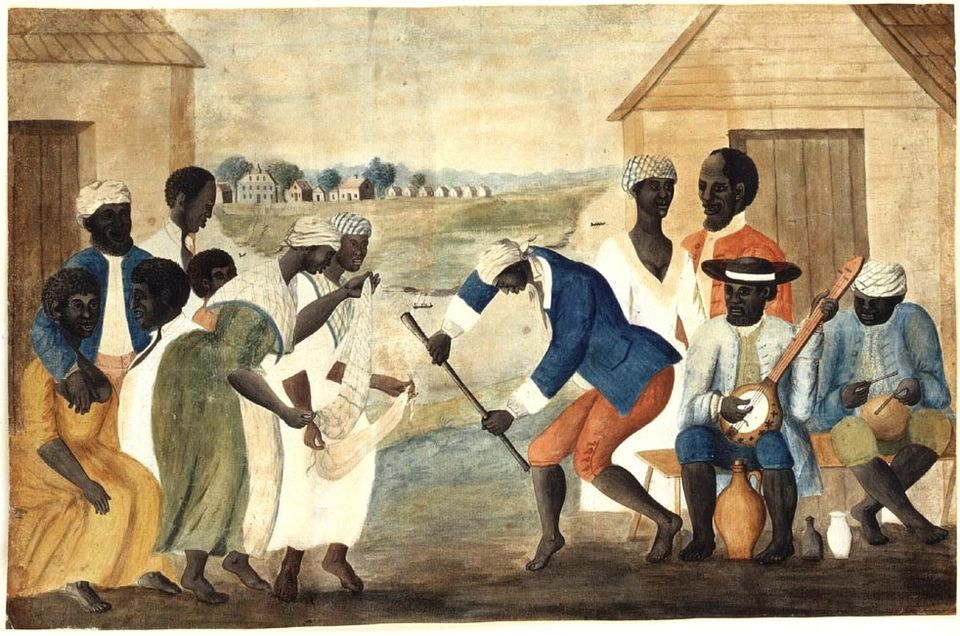

This late-eighteenth-century painting depicts enslaved people dancing and making music with a banjo and percussion instruments. It illustrates how rhythmic performance, song, and dance preserved African cultural elements and strengthened solidarity within enslaved communities. Background details of plantation buildings and landscape go beyond the syllabus focus but help contextualize these cultural practices. Source.

Creole languages, emerging from the blending of African and English linguistic patterns, facilitated community building and cultural continuity.

These cultural forms helped sustain hope, nurture pride, and strengthen communal bonds.

Community Networks and Survival Strategies

Mutual Support Systems

On plantations, in towns, and in port cities, enslaved Africans created networks that functioned as informal support systems.

Shared labor routines encouraged communication and relationship-building.

Collective care, including midwifery, healing, and food sharing, helped people endure hunger, injury, and emotional trauma.

Burial rituals and communal mourning honored ancestors and connected the living with cultural heritage.

These networks enabled enslaved people to confront the dehumanizing conditions of slavery with resilience and determination.

Negotiation and Adaptation

Although enslaved people had limited formal power, they occasionally used negotiation to secure modest improvements.

Some negotiated for task systems that provided free time after completing assigned work.

Others sought informal economic opportunities, such as gardening or small-scale trade, to support families and assert agency.

Through adaptation, enslaved communities maintained cultural practices while navigating the constraints imposed by colonial laws.

Together, resistance and cultural survival strategies demonstrate that enslaved Africans were not passive victims but active agents shaping their own lives and communities within the brutal context of early British America.

FAQ

Geography shaped both the opportunities and limitations for resistance. In regions with dense marshes, forests, or mountains, escape was more feasible, enabling longer-term flight and the possibility of joining maroon communities.

In areas dominated by large plantations, enslaved people often relied more heavily on covert resistance, as constant surveillance made open rebellion difficult. Urban environments, by contrast, provided access to wider networks of communication and sometimes allowed enslaved individuals to acquire skills that could facilitate acts of sabotage or evasion.

Enslaved artisans, sailors, carpenters, and blacksmiths often had greater mobility and contact with diverse groups, enabling them to spread information, organise covert acts, or forge networks beyond the plantation.

Skilled labourers sometimes manipulated their expertise to resist, such as deliberately slowing production, misusing specialised tools, or leveraging their skills to negotiate small concessions. Their unique position occasionally allowed them to secure limited autonomy or resources that supported wider community survival.

Names carried symbolic meaning, linking individuals to ancestors, ethnic groups, or personal attributes. Retaining African names helped preserve identity in a system designed to erase it.

Families sometimes used dual naming practices: an African-derived name within the community and a European name for interactions with enslavers. This strategy protected cultural continuity while navigating the colonial environment.

The practice also reinforced generational memory, allowing descendants to maintain connections to African heritage even when separated from their homelands.

Storytelling acted as a vehicle for shared wisdom, humour, and emotional resilience. Tales often encoded lessons about survival, resistance, and the value of communal support.

Common themes included cleverness overcoming power, adaptability, and warnings about betrayal or danger. These narratives shaped communal norms and moral frameworks.

Folklore provided a safe space to express criticism of enslavement indirectly. It also helped children learn cultural values and understand their community’s collective history.

Women bore unique burdens due to dual expectations of labour and caregiving. They played a central role in maintaining cultural practices, childrearing, and transmitting traditions despite long working hours and vulnerability to exploitation.

Men faced pressures to assert authority or leadership within communities, even though slavery restricted their roles. Both genders adapted to shifting family structures caused by forced separation.

Gendered experiences influenced resistance: women might resist through subtle acts within domestic spaces, while men might engage more frequently in physical defiance, although both forms were significant.

Practice Questions

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how enslaved Africans maintained cultural identity and community cohesion despite the oppressive conditions of chattel slavery in the British colonies. In your answer, refer to both cultural practices and social structures.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

Identifies at least two distinct ways enslaved Africans preserved cultural identity or built community (e.g., kinship networks, music and oral traditions, syncretic religious practices).

Provides basic explanation of each.

5 marks:

Shows clear analysis of how these practices helped maintain cohesion, resilience, or continuity under slavery.

6 marks:

Demonstrates well-developed analysis linking cultural and social strategies to broader survival, resistance, and community-building.

Uses accurate, detailed examples clearly drawn from the historical context.

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which enslaved Africans used covert resistance to challenge the system of slavery in the British colonies.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

Gives a basic but relevant statement about covert resistance (e.g., work slowdowns, feigned illness, tool-breaking).

2 marks:

Provides a clear explanation of the chosen method and how it undermined slaveholders’ control.

3 marks:

Offers a developed explanation linking the covert act to wider goals, such as asserting autonomy, disrupting plantation productivity, or maintaining dignity.