AP Syllabus focus:

‘All British colonies participated in the Atlantic slave trade to varying degrees; plantation regions held large enslaved populations, port cities had significant minorities, and most captives were sent to the West Indies.’

Slavery expanded rapidly in the British colonies as economic demand, environmental conditions, and demographic changes shaped varying regional labor systems tied to the wider Atlantic world.

Slavery’s Expansion in the British Atlantic World

The growth of slavery in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was driven by rising demand for labor-intensive staple crops, increasing European involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, and shifting colonial economic priorities. As enslaved Africans became central to colonial development, British America incorporated slavery at different scales and in different forms across its regions.

The Atlantic Slave Trade and British Participation

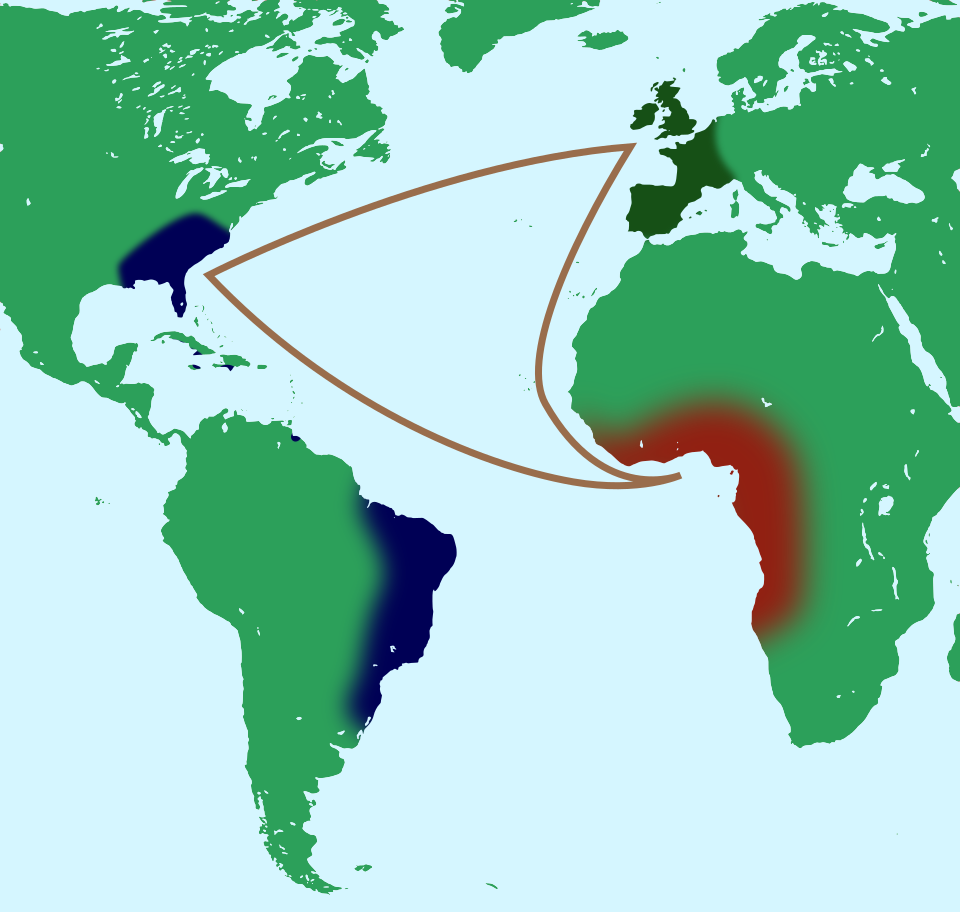

British merchants and colonial buyers became deeply embedded in the triangular trade, a system of exchange connecting Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

Map of the Atlantic triangular trade showing manufactured goods sailing from Western Europe to West Africa, enslaved Africans transported across the Middle Passage to the Americas, and plantation products shipped to Europe. The diagram clarifies how slavery in British America was embedded in a larger Atlantic exchange system. The map includes general Atlantic routes beyond the British Empire, but these additions remain appropriate for this AP topic. Source.

European goods such as textiles, firearms, and manufactured items were shipped to West Africa.

African traders sold captives—many taken in local conflicts or through expansive raiding networks—to European slavers.

Enslaved Africans were transported across the Middle Passage, a transatlantic journey marked by high mortality, overcrowding, and brutal conditions.

Plantation products like sugar, tobacco, rice, and indigo moved from the Americas to Europe, completing the circuit.

Most enslaved Africans transported on British ships were not taken to the North American mainland but to the British West Indies, where sugar production required immense labor. This pattern shaped demographic realities: the Caribbean received the highest volume of captives, while the mainland colonies absorbed smaller but steadily increasing numbers.

Labor Transitions and the Turn Toward Enslaved African Labor

In the early Chesapeake and parts of the lower South, colonial labor systems shifted from reliance on indentured servants to enslaved Africans. Indentured servitude — a labor system in which migrants worked for a fixed term in exchange for passage to the colonies — initially dominated tobacco-growing regions.

Indentured Servant: A laborer contracted to work for a set number of years in exchange for passage, food, and shelter, often with limited post-service opportunities.

As tobacco prices stabilized and landowners sought a more controllable, inheritable labor force, slavery expanded. English law increasingly codified perpetual, hereditary enslavement, supporting plantation profitability. Enslaved Africans became the primary labor source in regions cultivating staple crops that demanded year-round, intensive labor.

A wide range of environmental and economic conditions influenced where slavery grew fastest.

Long growing seasons in the lower South encouraged large-scale plantation agriculture.

Crop types such as rice and indigo required specialized knowledge, which African laborers often possessed.

Port cities benefited from enslaved labor in shipping, artisan trades, and domestic service, though in smaller proportions than plantation regions.

Regional Variation in Enslaved Populations

Slavery existed in every British colony, yet its scale, function, and social consequences differed sharply.

The Plantation South: High Enslaved Majorities

Plantation zones in the southern Atlantic coast—especially South Carolina and later Georgia—developed some of the largest enslaved populations in mainland British America.

The task system in rice-growing regions allowed enslaved people limited autonomy after completing daily assignments.

Harsh disease environments and high mortality rates shaped demographic instability, increasing reliance on continued importation of African captives.

Enslaved Africans often formed regional cultural identities, such as the Gullah culture in the Lowcountry.

These areas closely resembled the British West Indies in demographic composition and plantation structure.

The Chesapeake: A Mixed but Growing Slave Society

The Chesapeake colonies (Virginia and Maryland) transitioned from societies with slaves to full slave societies in which slavery became essential to economic production.

Tobacco cultivation required steady, disciplined labor.

As enslaved populations grew through both importation and natural increase, a distinct African American culture began to emerge.

Laws hardened racial boundaries, reinforcing lifelong enslavement and limiting opportunities for manumission.

The Middle Colonies and New England: Smaller but Significant Enslaved Minorities

Although less dependent on plantation crops, northern colonies still participated in slavery.

Port cities such as New York, Boston, and Philadelphia used enslaved labor in shipping, construction, skilled trades, and domestic service.

Northern merchants profited from provisioning Caribbean slave plantations and investing in transatlantic shipping ventures.

Enslaved populations remained minorities, but they shaped urban life and contributed to regional economies.

Demographic Patterns and Social Effects

The spread of slavery influenced population distribution, cultural life, and social structures.

Key Demographic Characteristics

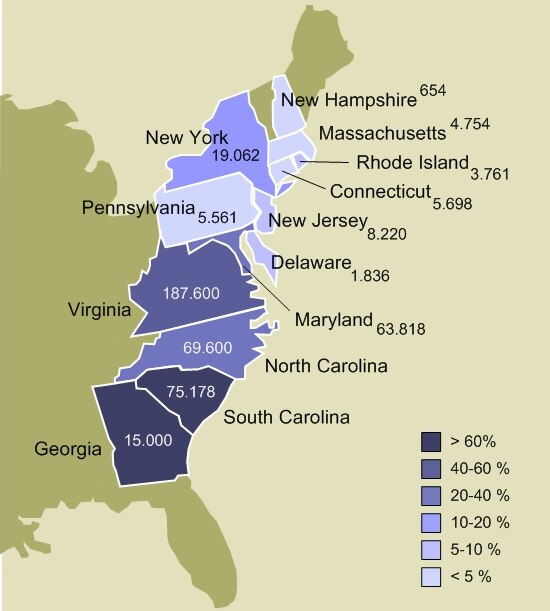

Slavery existed in every British colony, but its scale, economic role, and visibility in daily life differed sharply from region to region.

Map of the thirteen British colonies in 1770 showing each colony’s estimated enslaved population and shading that represents the percentage of the population enslaved. Darker tones over the Chesapeake and Lower South illustrate the regions where slavery was most dominant. Although slightly later than 1754, the distribution closely matches eighteenth-century regional variation described in this topic. Source.

Plantation colonies held some of the largest enslaved majorities on the mainland.

Northern and mid-Atlantic colonies had smaller enslaved communities but continuous economic ties to slavery.

The British West Indies, receiving the majority of captives, became the demographic center of Britain's slave system.

Social and Cultural Consequences

Slavery produced extensive cultural exchange and adaptation. Enslaved Africans maintained elements of language, religion, family structures, and artistic traditions while also developing new, syncretic forms of cultural life in British America. Regional differences in labor systems shaped the degree of autonomy, community cohesion, and cultural preservation available to enslaved people.

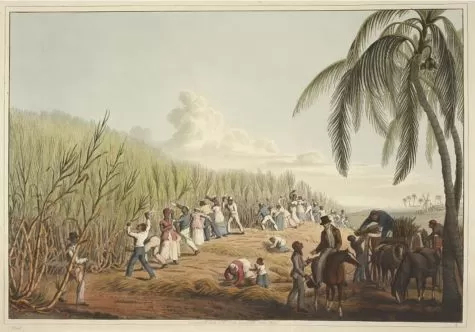

In the British West Indies, enslaved Africans often formed the overwhelming majority of the population, working on large sugar plantations that demanded year-round, intensive labor.

Illustration of enslaved laborers cutting sugar cane on a British Caribbean plantation in Antigua while an overseer on horseback supervises. The scene depicts the scale and intensity of plantation work in export-oriented sugar colonies with enslaved majorities. Though from 1823, the organization of labor reflects systems already well-established in the West Indies during the 1700s. Source.

The expansion and regional variation of slavery in the British colonies reflected economic needs, environmental conditions, and imperial priorities, all of which structured daily life across the Atlantic world.

FAQ

Shifts in market demand for crops such as rice, indigo, and later sugar influenced when regions intensified their use of enslaved labour.

As European consumption of plantation goods increased, colonies with fertile land and favourable climates expanded slavery earlier, while areas with mixed economies adopted enslaved labour more gradually.

Colonies tied to port-based commerce tended to experience delayed growth in enslaved populations because maritime and artisanal work required smaller, more flexible labour forces.

Many captives originated from West and West-Central African regions with expertise in rice cultivation, irrigation, and tropical agriculture.

This contributed to the rapid growth of slavery in the Lowcountry, where planters relied on African knowledge to establish profitable rice systems.

In contrast, northern colonies did not cultivate crops requiring specialised African expertise, so enslaved labour remained concentrated in domestic service and skilled trades.

Northern cities relied on enslaved labour for:

• Dock work and ship maintenance

• Urban construction trades

• Household and artisanal labour

Enslaved workers were also valuable for merchants involved in provisioning and financing Caribbean plantations.

Urban slavery persisted because it supported commercial activities linked to the Atlantic economy rather than agricultural production.

In the Caribbean and parts of the Lower South, high disease exposure led to extremely high mortality, preventing stable population growth.

Planters in these areas depended heavily on continual importation of African captives, reinforcing African cultural retention.

By contrast, the Chesapeake experienced comparatively lower mortality, allowing enslaved communities to grow through natural increase and develop more family-stable populations.

Colonial assemblies produced slave codes tailored to local economic needs.

Plantation colonies adopted strict codes to secure control over large enslaved majorities, reinforcing racial boundaries and hereditary enslavement.

Northern colonies enforced slavery through law but often regulated it within the context of smaller households and urban work, resulting in less centralised, though still restrictive, legal systems.

Practice Questions

Explain one reason why the expansion of slavery varied between different British colonial regions during the period 1607–1754. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason for regional variation in slavery (for example, differences in crop types, climate, or labour demands).

2 marks: Provides a simple explanation of how the identified reason influenced variation in the scale or nature of slavery.

3 marks: Gives a developed explanation that clearly links a regional factor to specific patterns, such as why plantation colonies developed large enslaved majorities while northern colonies had smaller enslaved populations.

Analyse how participation in the Atlantic slave trade shaped both the economy and demographic development of the British colonies between 1607 and 1754. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks: Describes at least one economic effect and one demographic effect of the Atlantic slave trade on the British colonies, with some relevant factual detail.

5 marks: Offers a clearer analytical explanation that links colonial economic growth or labour systems to the transatlantic movement of enslaved Africans, supported by specific evidence.

6 marks: Provides a well-developed analysis addressing both economic and demographic dimensions, showing how the colonies’ participation in the Atlantic slave trade shaped regional differences, labour systems, and population structures, using accurate and relevant historical evidence throughout.