AP Syllabus focus:

‘Renewed British imperial efforts after 1763 pushed many colonists to defend ideals of self-government, fueling organized resistance and a drive toward independence.’

After 1763, Britain’s new policies to tighten imperial control clashed with colonial expectations of autonomy, intensifying conflicts over taxation, representation, and authority that laid foundations for organized resistance.

Imperial Reforms After 1763

Following the Seven Years’ War, Britain sought to reorganize its empire to secure revenues, regulate commerce, and assert firmer authority in North America. The costly global conflict convinced British leaders that the colonies should contribute more directly to defending and administering the empire. This shift marked a profound departure from earlier decades of salutary neglect, a longstanding policy in which enforcement of imperial trade regulations was lax.

The End of Salutary Neglect

British policymakers believed tighter control was essential to prevent smuggling, regulate frontier settlement, and stabilize relations with Native nations.

They expanded customs enforcement.

They implemented new fiscal and administrative measures.

They demanded stricter adherence to imperial trade laws.

Salutary Neglect: A long-standing British policy of relaxed enforcement of colonial trade laws, allowing the colonies considerable self-governing freedom before 1763.

Parliament regarded these actions as reasonable governance, but colonists interpreted them as an erosion of rights and local authority.

Revenue Measures and Colonial Reaction

The most dramatic imperial reforms involved new revenue-raising acts. Britain expected colonists to help pay for imperial defense, but these policies challenged colonial understandings of representation and legislative authority.

The Sugar Act and Enforcement

The Sugar Act (1764) lowered the tax on foreign molasses but strengthened enforcement mechanisms to combat smuggling.

Admiralty courts tried suspected smugglers without juries.

Customs officials received expanded powers of search and seizure.

New documentation requirements tightened trade regulation.

Colonists objected not only to the economic consequences but also to the constitutional implications of enhanced imperial oversight.

The Stamp Act and Direct Taxation

The Stamp Act (1765) required purchased stamps for legal documents, newspapers, and printed materials. It represented the first direct tax imposed on colonists without their consent.

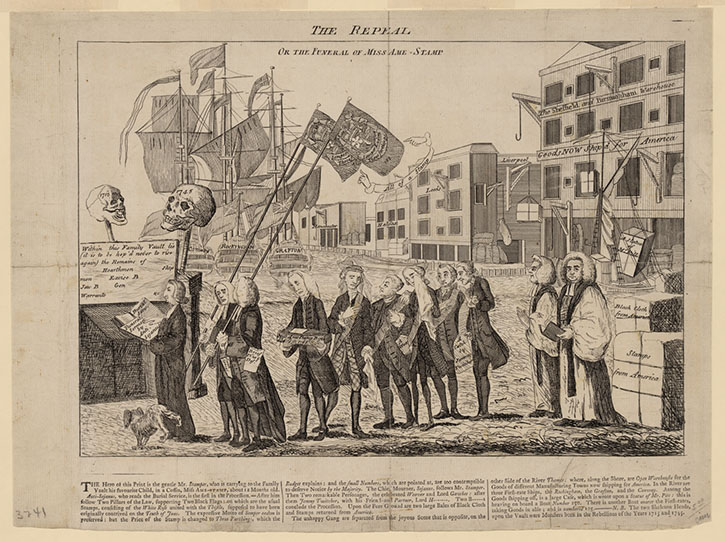

This cartoon depicts a mock funeral procession for the Stamp Act, symbolizing its repeal and illustrating widespread opposition to direct taxation. British politicians carry a coffin labeled “Miss Ame-Stamp,” representing the political costs of imposing the act. The background details of London are not mentioned in the notes but provide context for contemporary British reactions. Source.

Direct Tax: A tax imposed directly on individuals or transactions, requiring payment without intermediaries or local legislative approval.

This measure particularly affected influential groups—printers, lawyers, merchants—who quickly became vocal opponents.

Ideals of Self-Government and Rights

Britain’s reforms forced colonists to articulate longstanding political principles rooted in English traditions, colonial practice, and Enlightenment thought. Resistance framed taxation controversies as struggles over constitutional rights, not mere economic disagreements.

“No Taxation Without Representation”

Colonial critics insisted that only their own assemblies could tax them, drawing on the rights of British subjects and precedents of local self-rule.

They argued that representation in Parliament was distant and theoretical.

They emphasized the importance of consent in legitimate governance.

They invoked Enlightenment arguments about natural rights and limits on arbitrary authority.

Petitions, pamphlets, and public meetings promoted a shared language of political liberty.

Expanding Political Participation

Public debate encouraged broader civic involvement. Town meetings and local committees mobilized ordinary colonists who previously had little influence in imperial politics. As discussions widened, community expectations for accountability and transparency in government grew stronger.

Organized Colonial Resistance

Imperial reforms produced new, more coordinated forms of colonial activism. The colonies moved beyond isolated protests toward sustained, collective resistance.

Boycotts and Nonimportation

Merchants, artisans, and household consumers participated in organized nonimportation agreements, pledging to avoid British goods until objectionable laws were repealed.

Women played critical roles by producing homespun textiles.

Commercial pressure helped force the repeal of certain taxes.

Boycotts fostered a sense of shared political purpose.

These efforts transformed consumption into a political act and strengthened intercolonial communication networks.

The Sons of Liberty

The Sons of Liberty emerged in many port towns as activists who coordinated demonstrations, circulated information, and pressured stamp distributors to resign. While occasionally resorting to intimidation, they also provided structure to local resistance movements.

Intercolonial Cooperation: The Stamp Act Congress

The Stamp Act Congress (1765) gathered delegates from several colonies to articulate a unified response.

They issued declarations affirming colonial rights.

They asserted that taxation required representation.

They called for repeal rather than rebellion.

This congress marked an early step toward continental coordination, laying groundwork for later revolutionary institutions.

Escalation and British Reactions

British leaders maintained that Parliament held sovereign authority over the empire and rejected colonial distinctions between internal and external taxes. This disagreement led to escalating measures, including the Declaratory Act (1766) and the Townshend Acts (1767), which renewed colonial anger.

Rising Tensions

As protests intensified, Britain stationed troops in colonial cities to enforce order, further heightening friction. Violent incidents, such as confrontations in Boston, showed how imperial reforms had fundamentally altered colonial–British relations.

Toward Independence

By the early 1770s, repeated cycles of enforcement and resistance deepened mistrust on both sides.

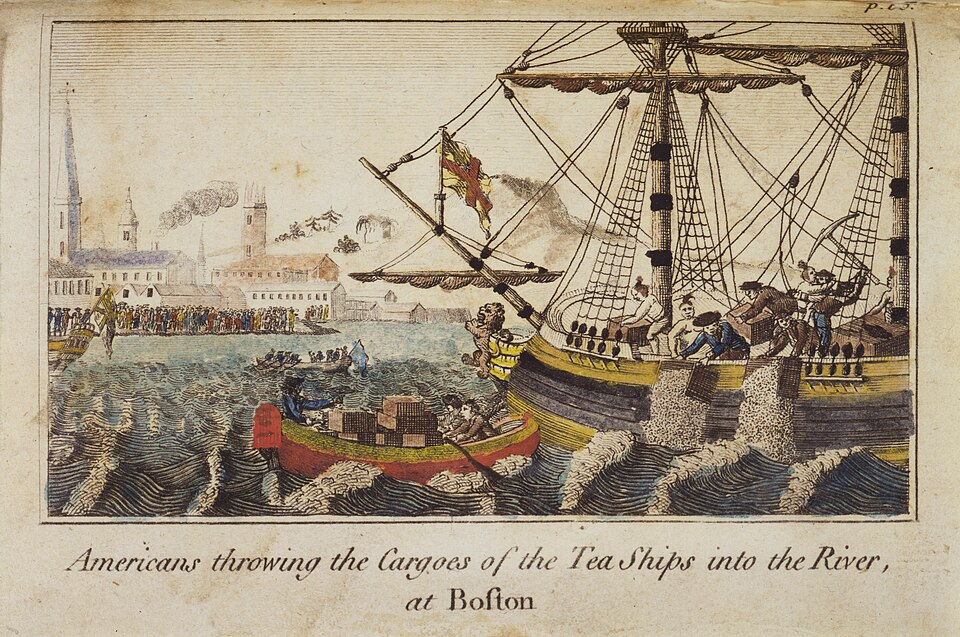

This engraving illustrates colonists throwing tea chests overboard in protest of British taxation and trade restrictions. It visualizes how resistance escalated from organized boycotts to direct action against imperial property. The engraving specifically depicts the Boston Tea Party, which is not named in the notes but exemplifies the broader resistance patterns described. Source.

Colonial leaders increasingly described these disputes as part of a broader struggle to preserve liberties, defend self-government, and resist perceived tyranny, setting the stage for the independence movement.

FAQ

Britain reorganised its customs service by creating the American Board of Customs Commissioners in 1767, centralising enforcement and reducing the autonomy of local officials.

It also increased the number of naval patrols along the American coastline to curb smuggling and authorised customs officers to use writs of assistance, which allowed broad searches for contraband.

These administrative adjustments signalled a shift from loosely supervised trade to a more intrusive imperial presence in daily colonial life.

Admiralty courts did not use juries, and cases were tried solely by a judge appointed by the Crown, which many colonists saw as undermining the right to a fair trial.

Convictions in these courts often led to the seizure of property, and the burden of proof fell more heavily on the accused than in common law courts.

Colonists viewed this as part of a wider pattern of imperial overreach and the erosion of English liberties.

Printers, pamphleteers, and newspaper editors played a key role in shaping public opinion by publishing essays, political cartoons, and reprinted speeches.

They standardised the language of rights, liberty, and constitutionalism, making resistance arguments accessible to a wide audience.

Print networks also helped coordinate protests by sharing news of meetings, boycotts, and legislative actions across colonial regions.

Many elites had longstanding economic, political, or social ties to Britain and feared instability that open resistance might invite.

However, increasing imperial intervention threatened their autonomy, particularly as Britain bypassed traditional colonial assemblies.

When popular movements grew, elites risked losing influence if they did not join or guide resistance, prompting a shift towards more assertive leadership.

Nonimportation agreements placed pressure on colonists to reject British manufactured goods, making domestic consumption choices expressions of political loyalty.

Households adopted homespun textiles and locally produced goods, turning ordinary activities—clothing production, tea consumption, shopping—into measures of commitment to the Patriot cause.

Women, in particular, gained political visibility through their central role in these domestic forms of resistance.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which British imperial reforms after 1763 contributed to growing colonial resistance.

Question 1

1 mark for identifying a relevant reform (e.g., Stamp Act, Sugar Act, increased customs enforcement).

1 mark for describing why colonists viewed the reform as a threat to their rights or self-government.

1 mark for explaining how this perception led to organised or ideological resistance (e.g., protests, boycotts, formation of the Sons of Liberty).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which colonial resistance to British policies in the 1760s and early 1770s was motivated by ideological commitments rather than economic grievances.

Question 2

1 mark for a clear statement of argument (e.g., resistance was primarily ideological, mainly economic, or a combination).

1–2 marks for explaining ideological motivations such as belief in rights of British subjects, consent to taxation, or traditions of self-government.

1–2 marks for explaining economic motivations such as the financial burden of taxes, trade restrictions, or impact on merchants and artisans.

1 mark for effective use of specific examples (e.g., Stamp Act Congress, nonimportation agreements, debates over representation).

1 mark for a concluding judgement about the relative strength of ideological versus economic factors.