AP Syllabus focus:

‘The American Revolution’s democratic and republican ideals inspired new experiments with government, including written constitutions and declarations of rights.’

Revolutionary Americans embraced new democratic and republican principles, prompting innovative governmental experiments that replaced monarchical authority with written constitutions, citizens’ rights, and unprecedented ideas about political representation and legitimate power.

Revolutionary Ideals and Experiments in Government

Democratic and Republican Thought in the Revolutionary Era

Revolutionary ideals emerged from the political, intellectual, and social transformations of the mid-eighteenth century. Colonists drew on Enlightenment philosophy, English constitutional traditions, and local practices of self-rule to envision a government grounded in the consent of the governed rather than inherited authority. These ideals challenged traditional monarchy and aristocracy, promoting the principle that political legitimacy derived from the people.

Republicanism: A political ideology holding that a nation’s authority comes from the people, who delegate power to representatives for the common good.

The shift toward republicanism encouraged Americans to believe that virtue, defined as the capacity of citizens and leaders to place public interest above personal gain, was essential for sustaining the new political order. Such thinking shaped debates over the distribution of political power, the design of governing institutions, and the nature of rights.

Written Constitutions as Expressions of Popular Authority

One of the clearest experiments in government was the creation of written state constitutions, documents meant to formally express the people’s will. Americans rejected the unwritten British constitution as insufficiently protective of liberty because it relied on custom and parliamentary supremacy.

These new constitutions aimed to institutionalize revolutionary ideals by:

Establishing governments based on popular sovereignty (the idea that power originates with the people)

Enumerating specific rights and liberties against governmental abuse

Structuring balanced governmental powers to prevent tyranny

Providing clear mechanisms for amendment and revision

State constitution writing represented a profound shift. Instead of evolving through tradition, government would now be deliberately constructed, debated, and ratified, making the people active creators of political order.

Declarations of Rights and the Protection of Individual Liberty

Many states included declarations of rights—formal statements of fundamental liberties that bound the government.

Facsimile of the first draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776), drafted primarily by George Mason for the new state constitution. It set out natural rights such as equality, popular sovereignty, and protections for jury trials, religion, and the press. The full document contains additional clauses and phrasing beyond what AP students must learn, but it demonstrates how revolutionary ideals became written legal guarantees. Source.

These declarations reflected both Enlightenment thought and colonial experience, emphasizing that natural rights existed prior to government and must be safeguarded.

Common rights listed across states included:

Freedom of speech, press, and assembly

Protection from arbitrary arrest and excessive punishment

Guarantees of jury trials

Rights to property and due process

Some declarations explicitly reaffirmed ideals from Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke, who argued that government existed to secure life, liberty, and property. These rights statements became key precedents for the later U.S. Bill of Rights.

Reconsidering Legislative, Executive, and Judicial Power

States experimented with institutional arrangements designed to embody Revolutionary ideals and avoid the perceived abuses of British rule. Most early constitutions strengthened legislatures, reflecting distrust of executive power associated with monarchy. Many states:

Created powerful, popularly elected legislatures

Weakened governors by limiting terms, veto power, or appointment authority

Ensured judicial independence but often made judges accountable through legislative review

However, these experiments revealed challenges. Concentrating authority in legislatures sometimes produced instability or factionalism. Such experiences later influenced calls for stronger, more balanced institutions during the drafting of the U.S. Constitution.

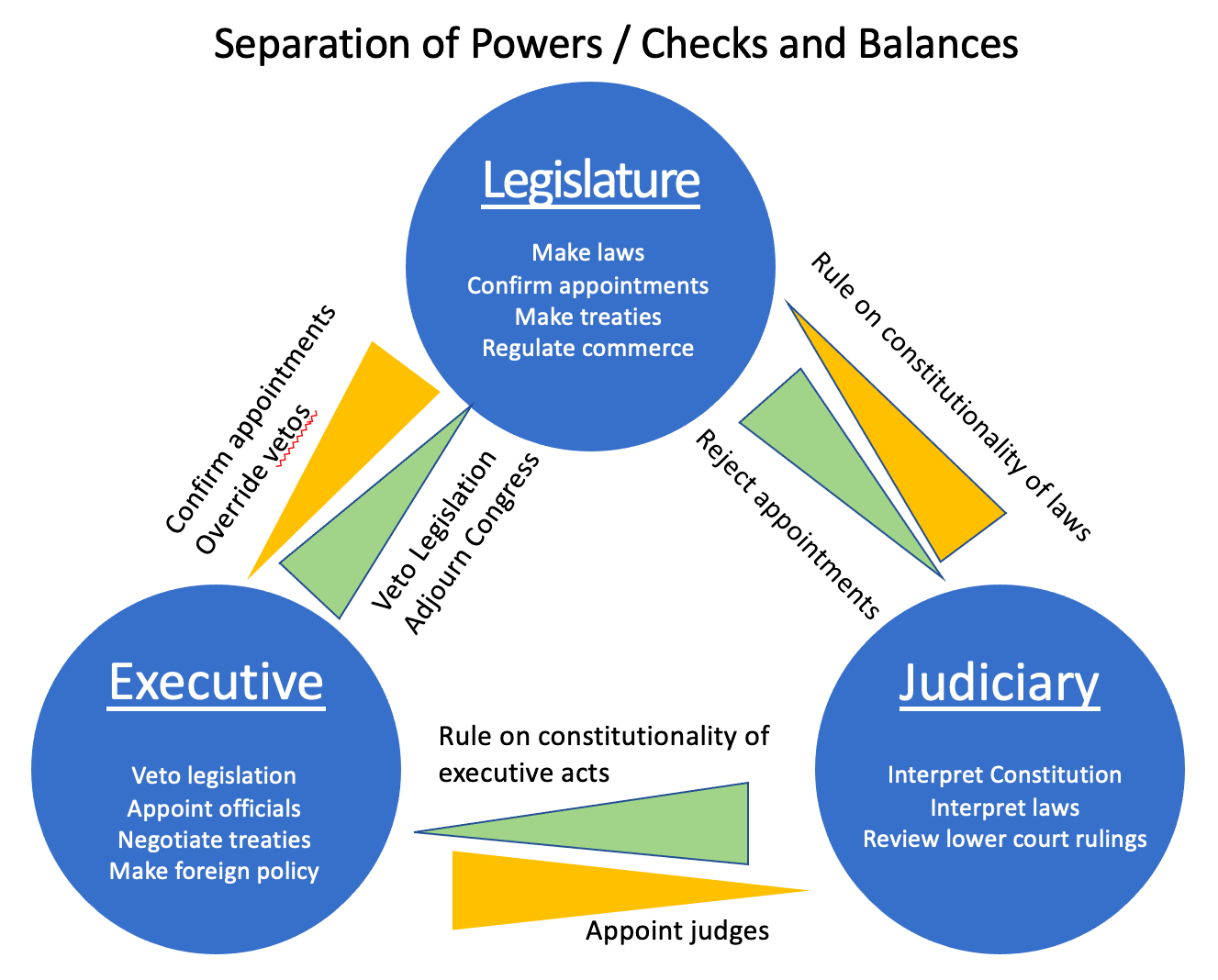

Most new constitutions—state and later federal—tried to prevent tyranny by separating powers among three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial.

Diagram of the U.S. system of separation of powers showing the three branches arranged in a triangle with arrows indicating checks and balances. It illustrates how written constitutions divided authority to prevent tyranny, a central experiment of the revolutionary period. The diagram includes additional modern details beyond syllabus requirements but helps visualize the overall structure. Source.

Expanding—but Also Limiting—Political Participation

Revolutionary ideals suggested greater inclusion in political life, yet the reality of political participation remained uneven. Many states maintained property requirements for voting or officeholding, reflecting fears that democracy without limits could lead to disorder.

Nonetheless, the period witnessed important expansions:

More white male property owners gained suffrage as requirements slightly loosened

Political debates increasingly emphasized the people’s right to participate

New civic expectations emerged concerning public virtue and informed citizenship

These changes indicated both the possibilities and constraints of applying democratic principles in the late eighteenth century.

Public Debates About Equality and Representation

The revolutionary emphasis on equality prompted Americans to reassess political representation. Many questioned systems that gave disproportionate power to wealthy elites or specific geographic regions. Discussions highlighted whether representatives should:

Mirror the population socially and economically

Act as independent, virtuous decision-makers insulated from public passions

Be elected frequently to ensure accountability

Such debates revealed the complexities of translating republican ideals into workable government structures. They also foreshadowed later national debates on representation in Congress during the Constitutional Convention.

Experiments in Confederation and Intergovernmental Cooperation

Revolutionary ideals also guided national-level experimentation. Even before independence was fully secured, states collaborated through the Articles of Confederation, the first national governing framework. While primarily a topic explored in later subsubtopics, the Articles grew directly out of the same republican commitment to limiting centralized power. The emphasis on state sovereignty reflected ongoing fears that concentrated authority, even in a republic, could threaten liberty.

Revolutionary Ideals as Foundations for Future Governance

The experiments of this era laid the groundwork for future political development. Americans embraced the idea that government must be consciously constructed, grounded in rights, and accountable to the people. These experiments—while imperfect—represented some of the most significant applications of revolutionary ideals and shaped the trajectory of American constitutionalism.

FAQ

Revolutionary ideals encouraged broader thinking about political participation, but debates remained contentious. Many leaders argued that only independent property owners possessed the civic virtue necessary for responsible decision-making.

Others pushed for wider inclusion, pointing out that if government derived its power from the people, then participation should not be restricted to the wealthy.

These disagreements shaped early policies on suffrage, officeholding, and citizenship, revealing tensions between egalitarian rhetoric and cautious governance.

Written constitutions signalled a deliberate and transparent creation of government, replacing inherited or unwritten traditions associated with monarchy. They served as visible guarantees of rights and limits on power.

For many Americans, the act of writing a constitution demonstrated that political power rested with the people, not a distant sovereign.

The physical document also provided a reference point for resolving disputes and guiding future political development.

The era’s focus on republican virtue led to expectations that leaders would prioritise the public good over personal ambition.

Key traits included:

Moderation in behaviour

Independence from corrupting influences

A commitment to civic duty

Leaders who appeared motivated by self-interest were viewed with suspicion, and debates about political structure often revolved around preventing such behaviour through balanced institutions.

Although all declarations emphasised natural rights, individual states crafted them to reflect regional priorities, political cultures, and recent experiences.

Differences included:

Varied emphasis on religious freedom

Distinct protections related to criminal procedure

Diverse wording on property rights

These variations reveal how revolutionary ideals were interpreted differently across the states, even as they shared broad philosophical foundations.

Implementing popular sovereignty required balancing public participation with stability and effective governance. States struggled with how frequently to hold elections, how much power to grant to legislatures, and how to limit corruption.

Other challenges included:

Managing factional divisions in rapidly changing political environments

Ensuring that citizens were sufficiently informed to participate meaningfully

Reconciling ideals of equality with persistent social hierarchies

These issues demonstrated the practical difficulties of turning revolutionary theory into functioning political systems.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which revolutionary ideals influenced the creation of written state constitutions during the American Revolution.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a relevant influence (e.g., belief in popular sovereignty, need to protect individual rights).

1 mark: Provides a clear explanation of how this ideal shaped the nature or structure of state constitutions.

1 mark: Uses accurate historical detail (e.g., constitutions being written documents expressing the will of the people, limits on executive power).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how experiments in government during the Revolutionary era reflected both democratic and republican principles. Use specific evidence from the period to support your answer.

Question 2

1 mark: Identifies democratic principles (e.g., expanded political participation, popular sovereignty).

1 mark: Identifies republican principles (e.g., emphasis on civic virtue, representative government).

1 mark: Explains how state constitutions embodied these principles.

1 mark: Includes specific examples (e.g., declarations of rights, weakened executive branches, strengthened legislatures).

1 mark: Demonstrates understanding of tensions, limits, or contradictions (e.g., property requirements, limited suffrage).

1 mark: Provides a coherent analysis linking ideals to governmental experiments rather than listing facts.