AP Syllabus focus:

‘Britain tried to tighten control over its North American colonies, while colonists increasingly insisted on self-government, setting the stage for an independence movement and war.’

Britain’s efforts to strengthen imperial control after decades of relative autonomy clashed with colonists’ growing commitment to local self-government, creating mounting tensions that foreshadowed revolutionary conflict.

Britain’s Expanding Imperial Vision

Throughout the mid-eighteenth century, Britain sought to consolidate authority over its North American colonies. After years of salutary neglect, a policy in which imperial enforcement of trade regulations was lax, imperial officials increasingly believed that stronger oversight was necessary to secure economic and strategic interests. This shift emerged from imperial competition, the financial burdens of warfare, and a desire to ensure colonial compliance with British trade and defense priorities.

Motivations Behind Tightened Control

British leaders in Parliament viewed the colonies as integral components of the empire’s commercial system. Their push for stronger authority stemmed from multiple objectives:

Standardizing imperial administration across diverse colonies with varying political traditions.

Ensuring adherence to mercantilist policies, which required colonies to enrich the mother country through regulated trade.

Managing imperial debt, heightened by earlier conflicts, by controlling colonial expenditures and introducing oversight mechanisms.

Strengthening defense coordination, especially as interactions with Native nations and rival European empires intensified.

The emphasis on these aims marked a decisive pivot toward centralization.

Colonial Traditions of Self-Government

Colonial societies had developed robust local political traditions. Many settlers were accustomed to representative assemblies, where elected legislators shaped taxation and local laws. When British officials attempted to reassert direct imperial control, colonists perceived an assault on what they believed were their established rights as British subjects.

Self-government: A system in which political power is exercised by locally elected representatives rather than by distant imperial authorities.

These traditions formed the backbone of colonial political identity, shaping expectations about autonomy within the empire.

By the mid-1700s, Britain ruled thirteen colonies along the Atlantic coast, each with its own governor, council, and elected assembly.

Map of the Thirteen Colonies in North America around 1775 under British rule. The colonies stretch along the Atlantic seaboard from New Hampshire to Georgia, illustrating the size and diversity of Britain’s North American possessions. Additional geographic labels that may appear extend beyond the syllabus but help contextualize the colonies within the wider region. Source.

Diverging Political Cultures

As Britain tightened administrative controls, deep differences between imperial and colonial understandings of power became increasingly clear. British policymakers believed in Parliament’s sovereignty—the doctrine that Parliament held supreme legislative authority throughout the empire. Colonists, however, believed their assemblies possessed legitimate authority over internal taxation and local governance.

The Role of Colonial Assemblies

Colonial assemblies assumed responsibility for:

Levying local taxes

Funding militias

Managing public works

Regulating local trade

Drafting laws tailored to regional conditions

Because these institutions had operated with relatively little interference for decades, they became central to colonial political life. Colonists argued that any challenge to their authority threatened the principles of liberty and property.

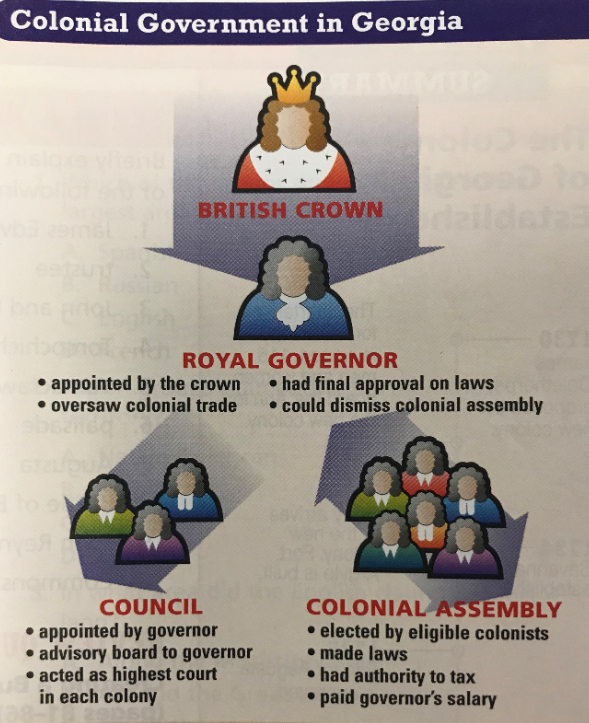

In a typical royal colony, a royal governor appointed by the king worked with an appointed council and an elected assembly, creating a layered imperial–colonial government.

Simplified diagram of colonial government in Georgia under royal rule. The British Crown appoints a royal governor, who works with an appointed council and an elected colonial assembly, illustrating how power flowed from London down to local institutions. The example is specific to Georgia, but the same basic structure applied across many royal colonies. Source.

British Attempts to Restructure Governance

Imperial administrators introduced several measures to increase oversight, including:

Increasing the presence and power of royal governors

Expanding enforcement of customs regulations

Limiting the autonomy of colonial legislatures in fiscal matters

Introducing policies designed to standardize administration across colonies

These actions reflected Britain’s broader goal of regularizing imperial governance, but they also signaled to colonists that longstanding self-governing practices were at risk.

Growing Friction and Resistance

As Britain asserted its authority more aggressively, colonial suspicion intensified. Colonists interpreted imperial reforms as evidence of an emerging plan to curtail local freedoms. This belief fueled anxieties that Britain aimed to reduce colonists to subordinate subjects without meaningful political participation.

Early Expressions of Colonial Resistance

Resistance began with political criticism and escalated into organized opposition. Key developments included:

Circulation of pamphlets defending the rights of colonial assemblies

Public meetings and correspondence between colonial leaders

Increased reliance on local networks of communication to oppose perceived infringements

Mobilization of community groups to pressure imperial officials

These actions demonstrated the depth of colonial commitment to self-rule and their growing willingness to challenge British authority.

Ideological Foundations of Colonial Defiance

Colonial resistance was underpinned by several ideological traditions:

English constitutionalism, which emphasized the rights of freeborn Englishmen

Republican thought, promoting civic virtue and vigilance against centralized tyranny

Localist political culture, which placed trust in nearby, representative institutions

Together, these ideas strengthened colonists’ resolve to defend self-government.

Tyranny: The exercise of power in an oppressive or arbitrary manner, often used by colonists to describe feared British overreach.

This concept helped articulate the colonial belief that imperial centralization threatened fundamental liberties.

Assemblies like Virginia’s House of Burgesses and Massachusetts’s General Court claimed the right to levy taxes and make internal laws, citing the tradition of English liberties.

Interior view of the House of Burgesses chamber in the Capitol at Williamsburg, Virginia. Here, elected colonial representatives debated laws, taxation, and the colony’s relationship with the royal governor, demonstrating the operation of local self-government. This is a modern photograph of a historical chamber but accurately reflects the layout of a colonial legislative assembly. Source.

The Stage Is Set for Conflict

By the early 1770s, Britain’s tightened control had produced deep resentment across the colonies. Although the empire sought administrative efficiency and stability, its actions unintentionally energized colonial political identity. The widening gap between British sovereignty and colonial self-government created a climate ripe for confrontation.

Preparing the Conditions for an Independence Movement

Several trends emerging during this period directly contributed to the later push for independence:

Strengthened colonial political networks and intercolonial cooperation

Greater public engagement in debates about rights and governance

Intensified distrust of imperial officials and royal authority

Growing belief that colonial liberties required active defense

Colonists increasingly concluded that remaining within the British Empire might endanger the self-governing principles they valued.

As Britain tightened control and colonists deepened their commitment to self-government, both sides became entrenched in opposing visions of authority. This clash laid essential groundwork for the independence movement and the war that followed.

FAQ

For decades, Britain informally followed a practice known as salutary neglect, allowing colonies to manage most internal affairs with minimal imperial supervision. This encouraged colonists to view local assemblies as the natural locus of authority.

Additionally, many colonial charters had originally granted broad governing powers, strengthening expectations that representative institutions would manage taxation, militia funding, and local regulations without direct intervention from London.

British policymakers felt that inconsistent colonial enforcement of trade laws weakened the mercantilist system. They also viewed colonial assemblies as increasingly assertive, sometimes challenging royal officials or obstructing defence measures.

Britain’s expanding commitments across the empire demanded clearer administrative coordination, and officials feared that loosely governed colonies might undermine imperial strategy or economic stability.

Colonists argued that because assemblies were elected by property-owning residents, they reflected the community’s consent in a way Parliament did not.

They also pointed to local precedents: assemblies had long controlled taxation for roads, local defence, and public institutions. This reinforced their belief that internal taxation was a provincial matter rooted in established political practice.

Colonial leaders relied on personal correspondence, printed pamphlets, and local meetings to share information and coordinate responses to imperial reforms.

These informal networks allowed ideas to spread quickly across regions, helping create a shared political vocabulary, including concepts such as liberty, arbitrary power, and defence of rights.

Royal governors used several tactics to strengthen imperial control, including:

• Refusing to approve assembly budgets until certain measures were passed.

• Dissolving assemblies that resisted directives from London.

• Attempting to increase the influence of appointed councils, which were more closely aligned with imperial interests.

These efforts often heightened tensions by reinforcing the colonists’ belief that imperial officials sought to restrict their political autonomy.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Explain one way in which Britain’s attempts to tighten control over the colonies in the mid-eighteenth century conflicted with colonial traditions of self-government.

Question 1:

1 mark: Provides a basic statement identifying a British attempt to tighten control (e.g., stricter enforcement of trade laws, increased authority of royal governors).

2 marks: Explains how this attempt conflicted with colonial expectations (e.g., assemblies were used to managing taxation and local decisions).

3 marks: Clearly connects the conflict to broader colonial beliefs about their rights as British subjects or long-standing practices of self-rule.

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Analyse the extent to which differing understandings of political authority between Britain and the colonies contributed to rising tensions before the American Revolution.

Question 2:

1–2 marks: Describes British ideas of authority (e.g., parliamentary sovereignty) or colonial views (e.g., rights of assemblies), but without full development.

3–4 marks: Explains how these differing views created tensions, providing specific examples such as disputes over taxation or governance.

5–6 marks: Offers a well-developed analysis that shows the extent of the contribution, making clear connections to the broader context of imperial reform, colonial resistance, and emerging revolutionary sentiment.