AP Syllabus focus:

‘As migrants moved westward from North America and abroad, frontier cultures grew, intensifying social, political, and ethnic tensions in new settlements.’

Westward migration reshaped early America as diverse settlers created new frontier societies. These communities fostered opportunity and conflict, transforming regional cultures and intensifying tensions across expanding settlements.

Westward Movement in the Early Republic

The decades following American independence witnessed significant westward migration, driven by demographic growth, economic ambition, and evolving federal land policies. Settlers moved beyond the Appalachian Mountains into territories such as Kentucky, Tennessee, the Ohio Valley, and further south and west.

Painting of Daniel Boone leading migrants through the Cumberland Gap, illustrating the westward movement of families into Kentucky and beyond. The image highlights how settlers crossed the Appalachians through narrow mountain passes. Although focused specifically on Boone, it represents broader late-18th-century migration patterns discussed in these notes. Source.

Motivations for Migration

A combination of economic opportunity, land availability, and strategic national goals fueled migration into new territories.

Population pressure in older coastal states encouraged families to seek farmland elsewhere.

Fertile soil in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys attracted agricultural communities.

Government policies, including land ordinances, facilitated structured settlement.

Speculators and land companies marketed frontier lands aggressively.

Immigrant groups, especially Scots-Irish and Germans, continued longstanding traditions of seeking autonomy in remote areas.

The ongoing presence and resistance of Indigenous nations shaped every aspect of this expansion. Migrants entered contested spaces that had political, cultural, and spiritual significance for Native peoples already living there.

Frontier Settlement Patterns

As migrants moved westward from North America and abroad, frontier cultures developed distinctive forms shaped by geography, isolation, and diverse cultural influences.

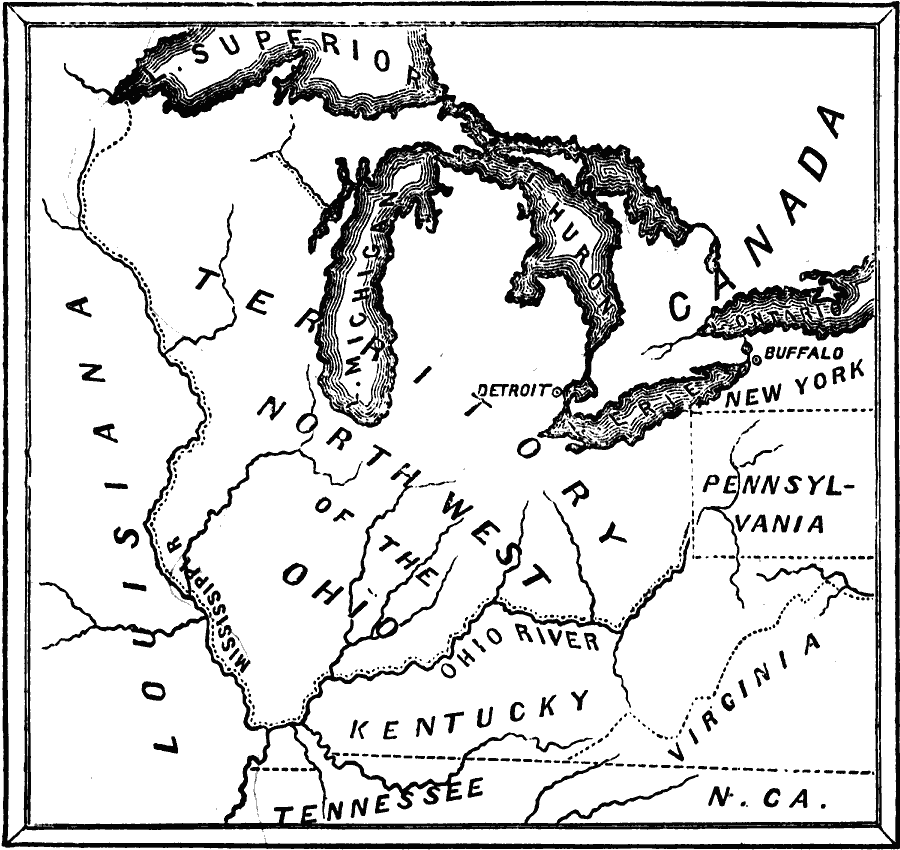

Map of the Northwest Territory and nearby regions, illustrating where many trans-Appalachian frontier communities formed. It shows the geographic framework of early settlements north of the Ohio River. The map includes territorial boundaries shaped by the Northwest Ordinance, which slightly exceeds the cultural focus of this section but provides essential spatial context. Source.

Settlements typically followed rivers and transportation corridors, creating scattered communities loosely tied to older eastern centers.

Map showing the Wilderness Road, a primary route guiding thousands of migrants through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky and the interior West. It illustrates how a single transportation corridor shaped settlement patterns across the frontier. The map also depicts later travel into the early 19th century, adding context slightly beyond the 1754–1800 focus. Source.

Frontier communities often shared several key characteristics:

Isolation, which encouraged high levels of self-sufficiency.

Small-scale family farming, bolstered by hunting and seasonal labor.

Informal governance, relying on local leaders and communal practices.

Multicultural populations, including Anglo-Americans, free and enslaved African Americans, European immigrants, and American Indian groups.

Despite their diversity, these settlements often celebrated an identity rooted in independence and adaptability.

Frontier: A region at the edge of established settlement, where sparse population, limited government structures, and cross-cultural encounters shape daily life.

Frontier spaces also acted as meeting points between different cultural worlds. Migrants brought religious traditions, agricultural techniques, and forms of social organization that blended with or confronted neighboring communities.

Formation of Frontier Cultures

The emergence of frontier cultures reflected the interaction of peoples and environments across newly settled regions.

Cultural Blending

Some areas experienced significant cultural blending:

German and Scots-Irish settlers shaped the backcountry’s language, architecture, and religious life.

African American influences—through both free communities and enslaved labor—were visible in foodways, music, and agricultural practices.

Indigenous knowledge, including hunting patterns, local geography, and crop cultivation, informed settler adaptation.

At the same time, cultural blending was uneven and often overshadowed by conflict and competition.

Social Norms and Identity

Frontier communities tended to cultivate a reputation for rough equality among white settlers. Wealth differences existed, but social relationships were less formal than in coastal cities. A culture of personal honor, local dispute resolution, and communal labor shaped local life.

However, this frontier “equality” excluded many. White settlers asserted dominance over Native nations and frequently marginalized African Americans, especially as slavery expanded into the Southwest.

Political and Social Tensions in New Settlements

The syllabus emphasizes how frontier development intensified social, political, and ethnic tensions. These tensions emerged from competing land claims, differing cultural expectations, and the rapid pace of change.

Land Conflict and Legal Disputes

Western migrants often entered lands claimed by multiple parties:

Indigenous nations defended their territories through negotiation, diplomacy, and armed resistance.

Settlers and speculators fought over overlapping deeds and unclear survey lines.

States and the federal government disputed jurisdiction over western lands.

Confusion and instability frequently led to violence or local mobilization. Frontier communities sometimes organized militias or vigilante groups to assert control.

Cultural and Ethnic Friction

The frontier brought diverse peoples into close—and often tense—contact.

Ethnic groups such as Scots-Irish, Germans, and English settlers sometimes clashed over religion, language, and customs.

Class tensions arose as wealthier landowners sought political dominance in emerging counties.

Racial tension increased with the presence of enslaved Africans and free Black communities, whose status alarmed some white settlers.

Indigenous–settler conflict remained the most persistent and consequential source of violence.

These tensions shaped local governance and influenced early national debates over expansion, security, and statehood.

Changing Political Dynamics

The growth of frontier populations altered the political landscape of the United States.

New states such as Kentucky and Tennessee entered the Union, strengthening western influence.

Frontier voters pushed for greater democratic participation, favoring leaders who championed land rights and local autonomy.

National parties increasingly appealed to western interests, foreshadowing the political prominence of frontier figures in the early nineteenth century.

Frontier demands for protection, infrastructure, and representation challenged federal leaders to balance expansion with diplomacy, economic strategy, and relations with Native nations.

Frontier Life and Economic Development

Economic life on the frontier centered on subsistence farming, barter systems, and limited market exchange. Over time:

New roads and river transport connected settlements to eastern markets.

Frontier agriculture diversified, including corn, livestock, and tobacco.

Trade with Native nations continued, though increasingly restricted by expansion pressures.

These developments tied frontier communities more closely to the national economy while also generating disputes over taxes, trade restrictions, and government authority.

Backcountry: Sparsely populated inland regions where settlers often relied on personal networks, informal law, and mixed subsistence economies.

Frontier communities frequently viewed central authority with suspicion, believing distant governments misunderstood or neglected their needs.

Migration’s Impact on Indigenous Nations

The expansion of frontier settlements profoundly affected Native nations across the early republic. As migrants claimed more land, Indigenous communities faced:

Displacement from ancestral territories.

Violence as settlers encroached on hunting grounds and villages.

Diplomatic pressure through treaties that often favored U.S. expansion.

Resource loss as forests, game, and river systems were altered.

These pressures spurred internal debate within Native nations about diplomacy, warfare, and alliances, contributing to cycles of resistance that shaped the early republic’s western borders.

Frontier Societies as Agents of Change

The complex mixture of migration, cultural exchange, and conflict made frontier societies powerful agents of change in the United States. Their demands, tensions, and innovations influenced national political culture, contributed to regional identity, and shaped ongoing debates about land, sovereignty, and the meaning of opportunity in the early American republic.

FAQ

Different ethnic groups migrated west for distinct reasons and often established culturally specific settlement patterns.

Scots-Irish communities tended to settle in upland, hilly terrain, maintaining traditions of clan-based social structure and Presbyterian worship.

German migrants often formed more cohesive farming villages, emphasising communal labour, stable family farms, and Lutheran or Reformed religious practices.

These groups interacted, traded, and occasionally clashed, contributing to the cultural mosaic of the frontier.

Taverns functioned as central hubs for information exchange, trade, and political discussion, often serving as informal courts or venues for community decisions.

Meeting houses or makeshift churches provided shared space for worship, dispute resolution, and social gatherings, reinforcing communal bonds.

Both institutions helped create a sense of collective identity in scattered settlements where formal governance was limited.

Migrants evaluated multiple environmental features before settling.

Factors included:

Access to fresh water sources or springs

Soil quality suitable for maize, tobacco, or mixed farming

Wooded areas for building materials and fuel

Proximity to foraging and hunting grounds

Such considerations shaped everything from house placement to livestock practices, contributing to regional variations in frontier culture.

Despite rising conflict, trade persisted because frontier communities relied on Indigenous knowledge and goods.

Indigenous peoples provided deerskins, furs, and regional geographic information, while settlers offered metal tools, textiles, and firearms.

However, growing distrust meant trade increasingly occurred through intermediaries or designated trading posts, often regulated by emerging state or federal policies.

These exchanges maintained economic interdependence even during political strain.

Frontier communities often developed improvised legal practices in the absence of strong state institutions.

Common methods included:

Local committees or councils mediating disputes

Community-enforced norms such as public shaming or restitution

Volunteer militias responding to theft, violence, or threats

Elected or respected figures acting as judges without formal training

These informal systems reinforced social cohesion but could also reflect local biases and uneven application of justice.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which westward migration contributed to the development of distinct frontier cultures in the early republic.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid way (e.g., geographic isolation, cultural blending, economic self-sufficiency).

1 mark for accurately describing how this factor shaped frontier communities (e.g., isolation encouraged informal governance).

1 mark for linking the development directly to westward migration (e.g., migrants moving beyond the Appalachians created scattered settlements that fostered new social norms).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which westward migration in the late eighteenth century intensified social, political, and ethnic tensions in frontier regions.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks for identifying relevant tensions (e.g., Indigenous–settler conflict, disputes over land claims, ethnic friction among settlers, class tensions).

1–2 marks for explaining how westward migration contributed to these tensions (e.g., competing claims between settlers and Native nations, diverse ethnic groups living in close proximity).

1–2 marks for providing analytical depth, such as evaluating which tensions were most significant, or showing how these tensions shaped emerging frontier governance or early U.S. policy.