AP Syllabus focus:

‘Slavery expanded into the deep South and adjacent western lands, strengthening plantation economies and shaping political and social power in the region.’

Expanding slavery into the Deep South and western territories reshaped regional economies, entrenched plantation systems, accelerated migration patterns, intensified sectional tensions, and created powerful economic and political structures dependent on enslaved labor.

Expansion of Slavery into the Deep South and West

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries witnessed the rapid spread of chattel slavery—a system in which individuals are legally considered property—across the Deep South and newly accessible western lands. This expansion was driven by economic opportunity, federal land policies, and the intensified global demand for agricultural commodities. As enslavers moved into regions such as Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, they brought with them economic expectations shaped by earlier plantation systems in the Atlantic South. Their migration also introduced a more rigid racial hierarchy and a dependence on coerced labor that profoundly transformed the political and social order of these territories.

Cotton, Land, and the Rise of a New Slave Economy

Cotton’s Dominance

The spread of slavery was inseparable from the rise of cotton, which became the dominant export commodity in the early republic. The international demand for cotton surged dramatically, and the Deep South’s fertile lands proved ideal for its cultivation.

Staple Crop: A crop produced in large quantities that forms the basis of a region’s agricultural economy.

One reason cotton became so central was the development of long-staple and short-staple varieties, with the latter able to grow across much of the South. Short-staple cotton thrived in inland areas once considered unsuitable for plantation agriculture, pushing enslavers to acquire new lands and expand production zones.

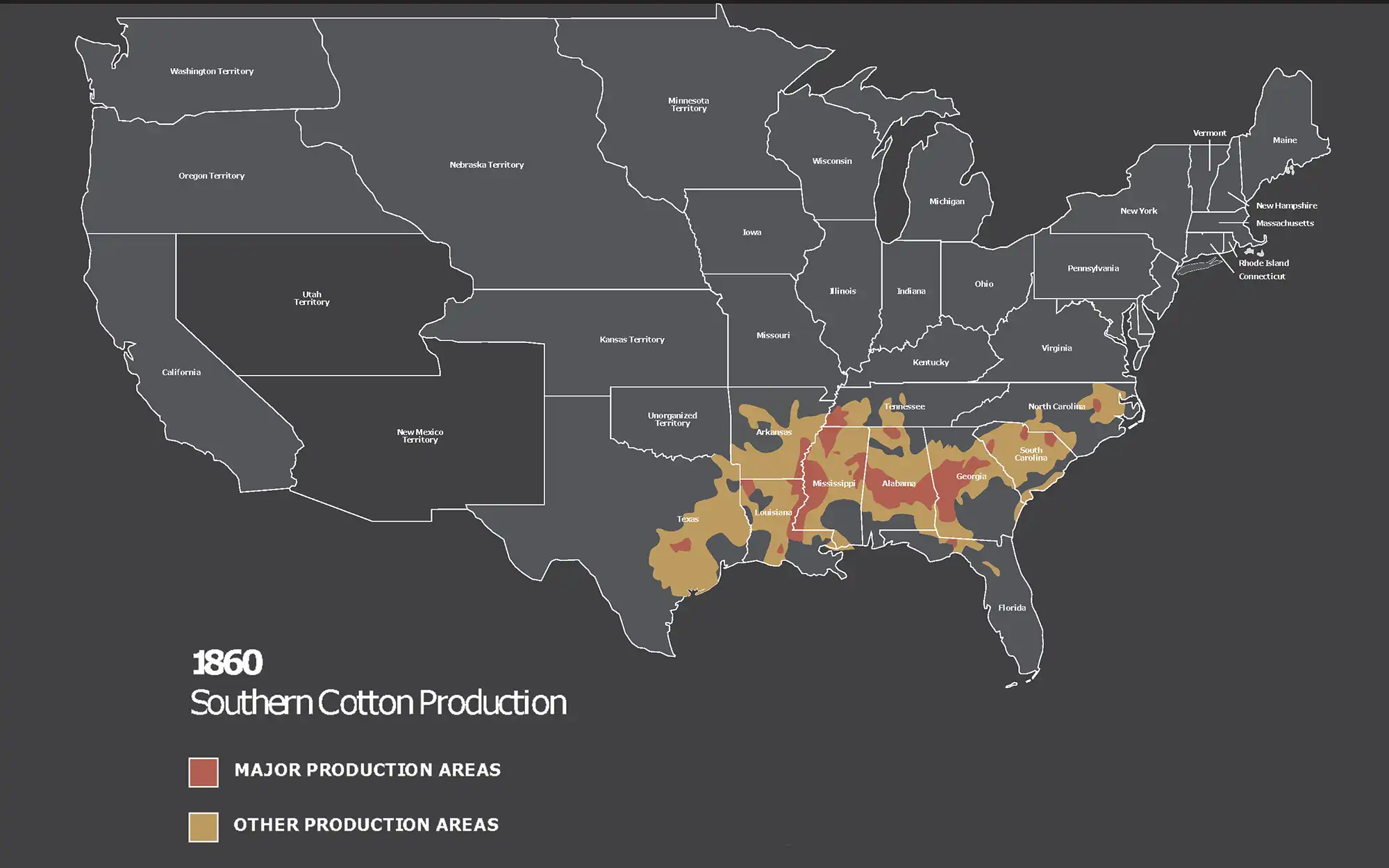

This map of Southern cotton production in 1860 shows major and secondary cotton belts across the Deep South. It illustrates how cotton cultivation concentrated in states like Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, reinforcing the westward spread of slavery. The map includes some areas not emphasized in the syllabus, but these additions help contextualize the broader agricultural landscape. Source.

Federal Support for Westward Agricultural Expansion

Federal policies encouraged movement into western territories, indirectly promoting the spread of slavery.

Land ordinances opened territories for settlement, creating opportunities for plantation expansion.

Treaties and forced removal of Indigenous nations increased the availability of fertile land.

New states admitted from these regions often permitted slavery, strengthening the institution politically.

Together, these developments transformed the Deep South into the nation’s primary zone of enslaved labor.

Plantation Economies and Labor Intensification

Structure of Plantation Labor

As slavery expanded westward, plantation owners created large, profit-driven agricultural complexes structured around the forced labor of enslaved Africans and African Americans. These plantations grew to unprecedented scale, using labor systems designed to extract maximum productivity.

The gang system, which organized enslaved laborers into supervised groups, became widespread across cotton plantations.

The movement of enslaved people through the internal slave trade redistributed populations across the South.

Large capital investments into land and enslaved individuals reinforced the economic centrality of slavery.

Internal Slave Trade: The system of buying, selling, and relocating enslaved people within the United States after the international slave trade was banned.

As plantations expanded, enslaved communities were fractured by forced migrations that moved people hundreds of miles from their homes in the Upper South.

Social and Political Power in the Expanding Slave South

The Rise of the Slaveholding Elite

The growth of slavery created a powerful planter aristocracy, a small but influential class of wealthy enslavers whose economic dominance translated directly into political influence.

They accumulated land, capital, and enslaved laborers at far greater rates than small farmers.

Their status shaped local governance, state constitutions, and federal policy positions.

They promoted a racial ideology that justified slavery as a natural and essential institution.

Planter influence ensured that proslavery legislation, property protections for slaveholders, and land policies favorable to plantation expansion remained central features of southern politics.

The Entrenchment of Racial Hierarchy

Slavery’s spread intensified a rigid racial order that shaped society in the Deep South and West.

Laws increasingly defined enslaved people as property with no legal personhood.

Racial hierarchies structured access to land, political participation, and economic opportunity.

Free Black people faced severe restrictions to prevent social mobility or legal challenges to slavery.

This system became deeply entrenched as slavery expanded geographically.

Migration, Settlement, and Regional Transformation

Movement of Enslavers and Enslaved People

The Deep South became known as the Cotton Kingdom, reflecting its economic dependence on cotton production and enslaved labor.

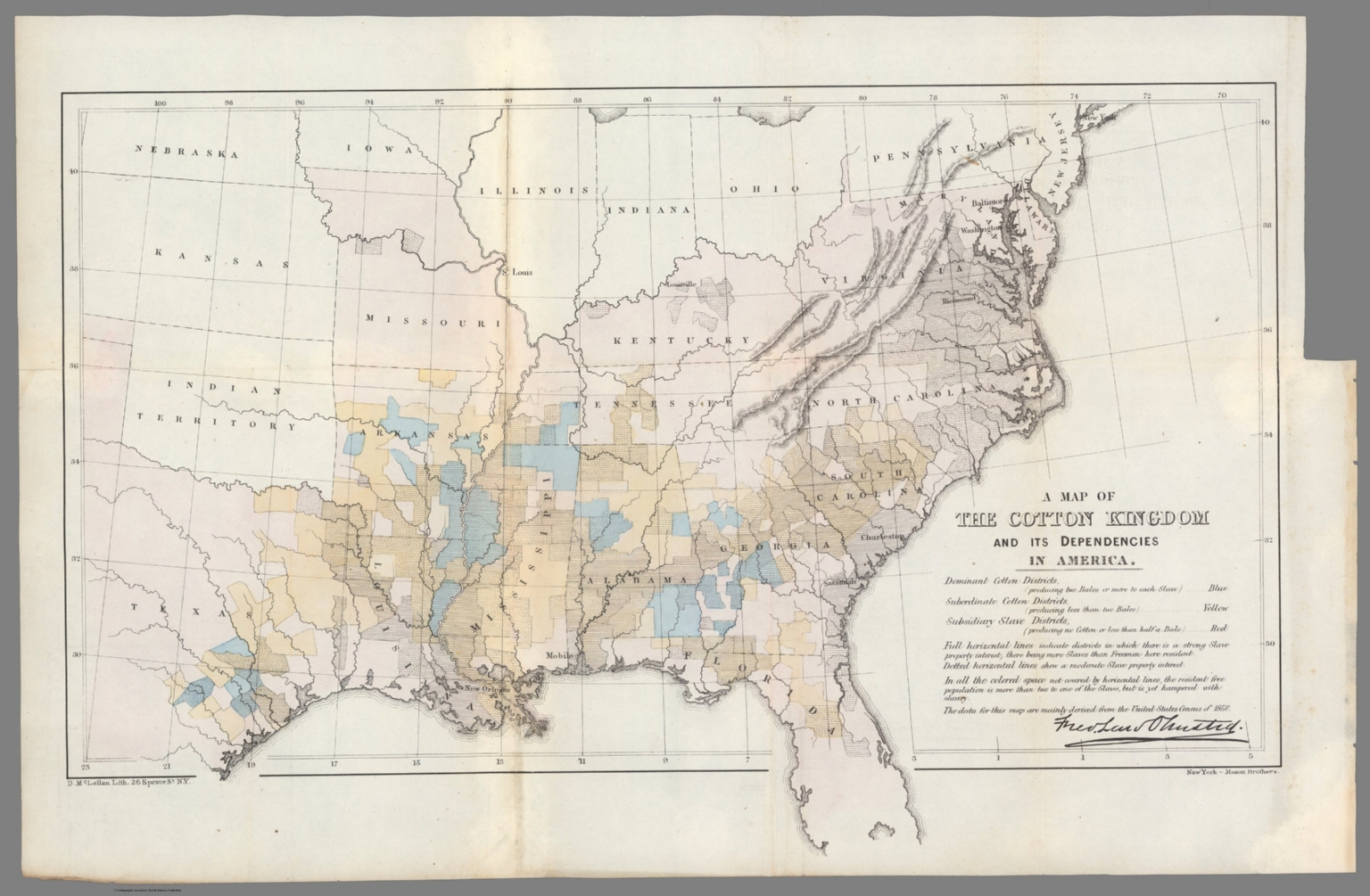

This 1861 map of the Cotton Kingdom marks dominant and subordinate cotton districts and regions economically tied to slave labor. Its color shading highlights how the Deep South formed the core of cotton production while neighboring areas remained deeply connected to this system. Some labeled regions extend beyond the syllabus, but they help clarify broader economic linkages. Source.

Migration patterns reflected both coercion and opportunity:

Enslaved people were forcibly relocated through the domestic slave trade.

White farmers and planters moved voluntarily to seek new lands.

Emerging towns and transportation networks supported export-oriented agriculture.

The resulting demographic shifts produced a region dominated by large plantations and sparsely populated rural settlements where slavery shaped daily life.

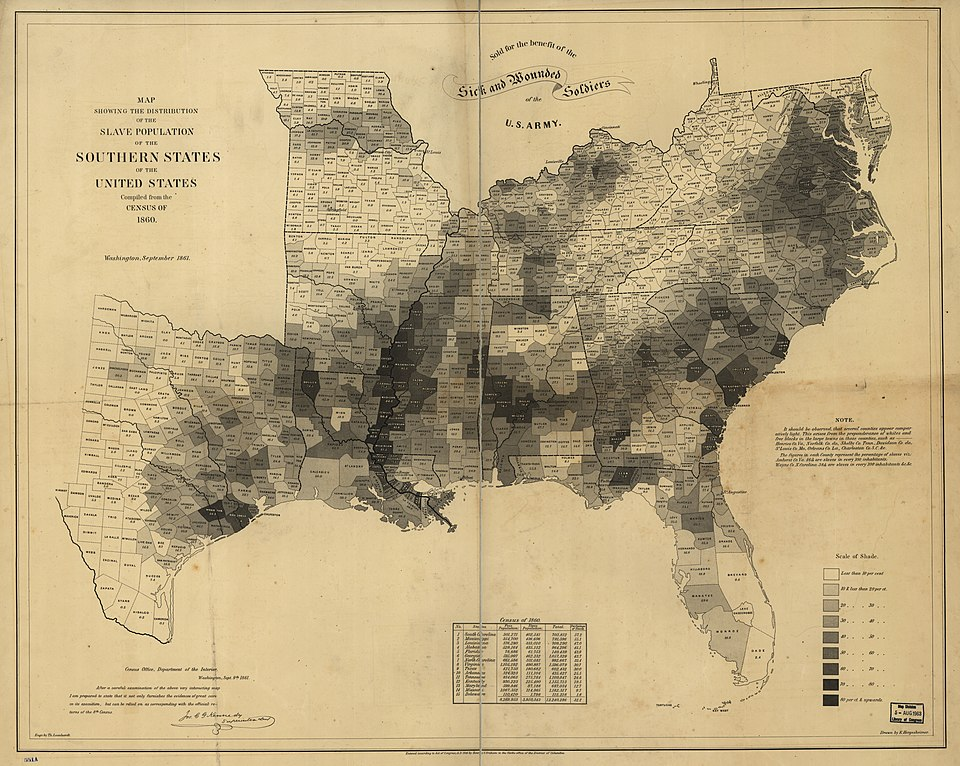

This 1860 U.S. Coast Survey map illustrates the percentage of enslaved residents by county across the South, with darker shading marking higher concentrations. It visually reinforces how enslaved labor dominated large parts of the Deep South and river valleys. Some areas shown are outside the syllabus focus, but these additions help contextualize regional demographic patterns. Source.

Western Territories and the Future of Slavery

As slavery expanded, its future became a central national political issue. Whether new western territories would permit slavery shaped political debates, influenced party formations, and intensified sectional conflict between North and South. The economic success of slavery in the Deep South strengthened southern arguments for further expansion, setting the stage for future national turmoil.

Economic and Social Consequences of Expansion

The spread of slavery enriched enslavers and integrated the Deep South into global markets, but it also entrenched systemic inequalities. Wealth concentrated among plantation owners, reducing economic diversity and limiting opportunities for small farmers, free laborers, and non-elite whites. At the same time, enslaved people endured increasingly harsh conditions as demand for labor rose and cotton cultivation intensified.

The expansion of slavery into the Deep South and West thus reshaped the economic foundations, political structures, and racial dynamics of the region, establishing patterns that would influence national debates and conflicts for decades to come.

FAQ

The internal slave trade moved enslaved people primarily from the Upper South to newly developing cotton regions. Traders often organised large overland “coffles” or transported captives by ship down the Atlantic coast or Mississippi River.

Sales were arranged through markets in cities such as Richmond, Charleston, and New Orleans, connecting older slaveholding regions to emergent plantation zones.

Families were frequently separated, and prices rose as demand intensified in the cotton-producing territories.

Short-staple cotton tolerates diverse soils and climates, unlike long-staple varieties that required specific coastal environments. This adaptability allowed cotton plantations to spread far into inland areas of the Deep South.

Additionally:

• It could be grown in previously undeveloped frontier lands.

• High international demand made it extremely profitable.

• Expansion relied heavily on forced labour, tying its growth directly to the spread of slavery.

Southern banks issued loans based on land and enslaved people, both treated as capital assets. This enabled planters to purchase more land and expand operations into western territories.

Credit networks connected merchants, exporters, and planters, making plantation expansion financially viable.

However, reliance on credit increased economic vulnerability, tying regional prosperity closely to commodity prices and international markets.

Enslavers sought fertile lands occupied by Indigenous nations, particularly the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Cherokee. U.S. policies and treaties enabled the government to acquire these lands.

Key processes included:

• Federal pressure leading to cessions and removals.

• Military enforcement of land transfers.

• Immediate resale of these lands to cotton planters.

This dispossession created the territorial foundation for large-scale slave-based agriculture.

Poor white settlers often struggled to compete with wealthy planters who controlled most fertile land and capital, limiting opportunities for upward mobility. Many became subsistence farmers on marginal land.

Socially, racial hierarchy offered them legal and cultural privileges relative to enslaved people, reinforcing loyalty to the slave system.

Economically, plantation dominance reduced the diversification of regional industries, constraining job prospects outside agriculture.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why the expansion of cotton cultivation contributed to the spread of slavery into the Deep South and western territories in the early nineteenth century.

Question 1

1 mark:

• Identifies a basic reason, such as increased demand for labour or profitability of cotton.

2 marks:

• Provides a developed explanation, for example noting that short-staple cotton could grow in a wide range of southern environments and therefore encouraged expansion into new lands.

3 marks:

• Gives a well-developed explanation linking cotton cultivation to the growth of slavery, such as describing how expanding markets increased the need for enslaved labour, stimulating migration of enslavers into the Deep South and reinforcing the economic viability of slavery in newly settled territories.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the growth of plantation economies in the Deep South shaped political and social power structures in the region between 1800 and 1860.

Question 2

4 marks:

• Offers a general explanation of how plantation growth shaped political and social structures.

• Mentions at least one example, such as the rise of a wealthy planter elite or the entrenchment of racial hierarchy.

5 marks:

• Provides a more detailed analysis demonstrating clear links between economic expansion, political dominance of slaveholders, and social stratification.

• Shows understanding of how plantation wealth translated into influence over state legislatures, local courts, or voting qualifications.

6 marks:

• Presents a well-structured, analytical response connecting multiple factors (economic, political, and social).

• Explains how the concentration of land and enslaved labour created an elite class that shaped policy and defended the institution of slavery.

• Describes the impact on broader society, including restrictions on free Black people and limited opportunities for poorer white farmers, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of regional power dynamics.