AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rising antislavery sentiment, alongside expanding slavery, created distinctive regional attitudes toward slavery that would shape debates into the nineteenth century.’

Growing antislavery sentiment in the early republic developed unevenly across regions, intensifying political, cultural, and economic divisions that shaped emerging national debates over slavery’s morality, expansion, and future.

Antislavery Sentiment and Its Early Growth

In the decades following the American Revolution, a noticeable rise in antislavery sentiment emerged, particularly in northern states where Enlightenment ideas, evangelical religious revivals, and shifting economic structures encouraged critiques of bondage. This growing opposition to slavery formed a key part of the national landscape, even as slavery simultaneously expanded in the South.

Intellectual and Moral Foundations of Antislavery Beliefs

Many Americans in the North adopted antislavery views through a combination of republican ideals, religious conviction, and broader debates about the meaning of liberty after independence.

Enlightenment thought highlighted human equality and natural rights, challenging hereditary privilege and, by extension, slavery.

Evangelical Protestantism, especially during the early stirrings of the Second Great Awakening, promoted moral reform and emphasized the equality of souls before God.

Revolutionary rhetoric celebrating liberty, individual rights, and self-rule made slavery appear increasingly incompatible with the nation’s founding principles.

Natural rights: Fundamental rights believed to belong to every person by virtue of being human, often invoked to question slavery’s legitimacy.

Northern antislavery voices framed slavery as a moral wrong and a threat to republican virtue because it concentrated power in the hands of wealthy slaveholders.

These ideas circulated through sermons, pamphlets, and state debates, encouraging further critique.

Regional Differences in Slavery and Antislavery Development

Distinct regional paths emerged as the United States expanded westward and confronted new economic and demographic realities.

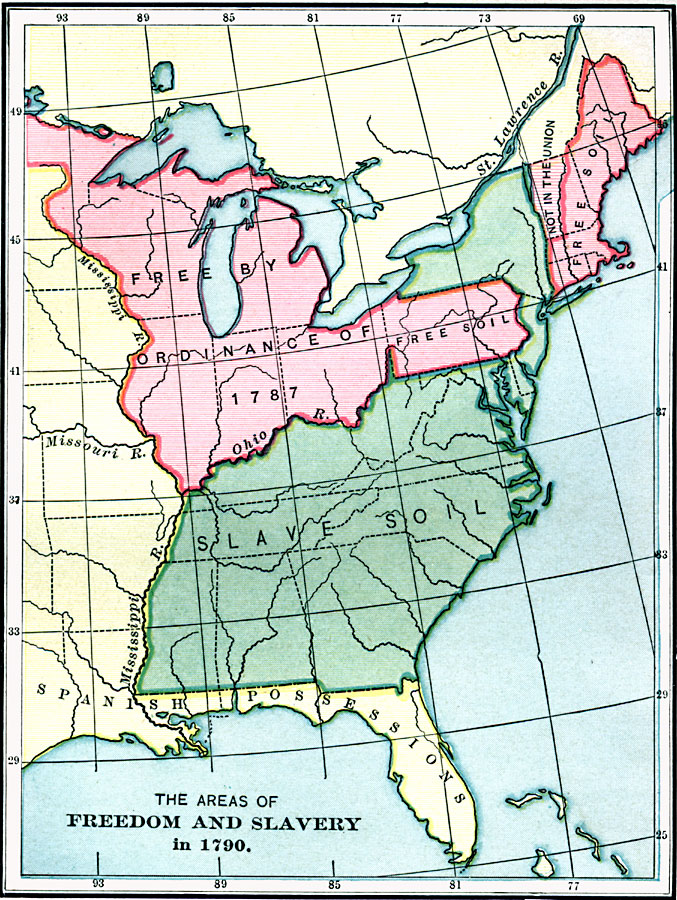

This map depicts divisions between free and slave soil in the United States around 1790, including the Northwest Territory made free by the Ordinance of 1787. It helps illustrate how slavery was concentrated in the South while being restricted or abolished in northern and northwestern regions. Some territorial labels extend beyond syllabus requirements but clarify how early policies shaped emerging sectional differences. Source.

The North: Gradual Emancipation and Free Black Communities

Several northern states pursued gradual emancipation, a legislative process in which enslaved individuals were freed over time while protecting existing property rights.

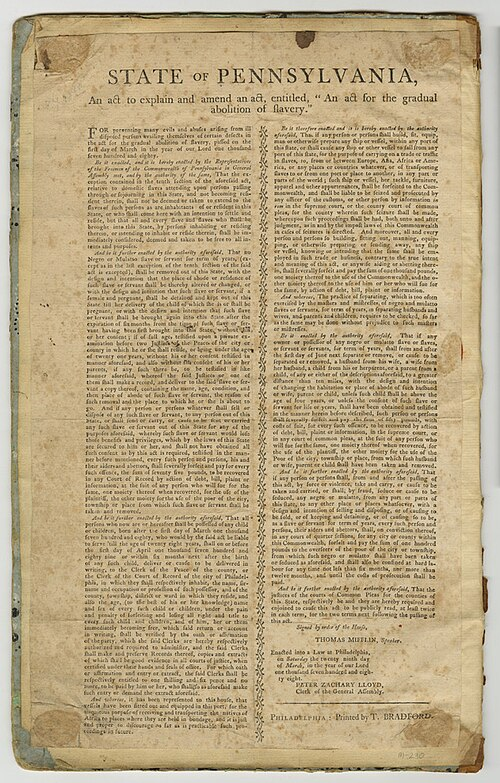

This printed broadside announces Pennsylvania’s act for the gradual abolition of slavery, one of the earliest state laws phasing out slavery after the Revolution. It exemplifies how northern legislators translated antislavery ideas into cautious legal reforms rather than immediate emancipation. The dense legal text exceeds syllabus needs but illustrates how gradual emancipation functioned in practice. Source.

States such as Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey enacted laws phasing out slavery across decades.

Gradualism reflected both humanitarian impulses and economic realities, as slavery had become less central to northern commercial and industrial development.

A growing population of free Black Americans emerged, forming communities, churches, and mutual aid organizations that expanded antislavery activism.

While racism persisted, the North increasingly framed itself as a region where slavery was declining and freedom was expanding. This shift contributed to political coalitions that opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories.

The Upper South: Mixed Attitudes and Limited Reform

States such as Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware showed some early stirrings of antislavery sentiment.

Slaveholders debated the future of the institution, with some expressing doubts about slavery’s long-term sustainability.

A small but notable number of manumissions created a modest free Black population.

However, slavery remained economically valuable in tobacco and mixed farming regions, limiting large-scale reform.

This middle-ground position reflected the Upper South’s transitional economic structure—less reliant on plantation slavery than the Deep South but still deeply tied to enslaved labor.

Expansion of Slavery and Intensifying Sectionalism in the Deep South

In contrast, the Deep South entrenched slavery even more firmly due to booming cotton production and expanding global demand.

Plantation economy: An agricultural system relying on large-scale landholdings and enslaved labor to produce cash crops for export.

Innovations such as the cotton gin, along with fertile lands in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, strengthened slavery’s central role in the regional economy.

Slaveholders defended slavery as essential for economic prosperity.

Racial ideologies hardened, promoting the belief that slavery was a “positive good” rather than a necessary evil.

Migration from older southern states pushed enslaved people into newly opened western territories, reinforcing slavery’s expansion.

These developments created an ideological contrast with the North, where free labor increasingly defined economic identity.

Political Implications of Antislavery Sentiment

Regional differences in attitudes toward slavery had profound political effects.

Northern Political Mobilization

Growing antislavery beliefs helped shape early political debates:

Voters and legislators in the North increasingly resisted policies that expanded slavery westward.

Antislavery activists, though not yet abolitionists in the modern sense, pressured leaders to limit the institution’s reach.

Free labor ideology—the belief that economic opportunity depended on free rather than enslaved labor—gained momentum.

Southern Political Defense

Southern elites responded by tightening defenses of slavery.

Slave codes were strengthened to restrict the movement, education, and assembly of enslaved people.

Politicians emphasized states’ rights arguments to shield slavery from federal interference.

Southern representatives sought to maintain parity in Congress to protect the institution.

This defensive posture reflected regional fears that the growing antislavery sentiment in the North posed a direct threat to the South’s social and economic systems.

Cultural and Social Divergence

As attitudes diverged, cultural identities also shifted.

Northern reform movements increasingly linked antislavery with broader humanitarian causes.

Southern society celebrated plantation life and emphasized hierarchical social structures rooted in racial slavery.

Migration patterns contributed to these differences: northerners moving west brought free labor ideals, while southern migrants carried slavery into the Mississippi Valley.

These cultural, political, and economic contrasts hardened into sectional divisions that would continue to shape national debates into the nineteenth century, fulfilling the syllabus focus on rising antislavery sentiment and its lasting regional impact.

FAQ

Free Black communities offered some of the earliest organised challenges to slavery and racial inequality. Their churches, mutual aid societies, and literary publications helped articulate moral and political arguments against bondage.

Their activism also provided white reformers with models of civic participation, reinforcing Northern views that free labour societies were both possible and desirable.

Religious denominations often split along regional lines as disagreements over slavery intensified.

Northern branches of Methodist, Baptist, and Quaker communities increasingly condemned slavery as incompatible with Christian morality.

Southern branches tended to defend slavery or avoid direct condemnation, reflecting local economic and social priorities.

These divisions deepened the wider cultural and ideological gap between regions.

Gradual emancipation laws were shaped by local economies, political cultures, and the size of the enslaved population. States with limited reliance on enslaved labour, such as Pennsylvania, moved more quickly, while others phased emancipation over longer periods.

Different lawmakers also balanced moral concerns with fears of social disruption, leading to varied timelines and conditions for freedom.

Southern elites believed slavery was essential to maintaining social hierarchy and preventing potential uprisings. Enslaved labourers far outnumbered white populations in some areas, intensifying concerns about instability.

These fears encouraged stricter slave codes, political resistance to abolition, and the promotion of pro-slavery ideology as a means of preserving regional security.

Westward migration brought Northern and Southern settlers into closer contact, each carrying their own labour systems and cultural expectations.

Conflicts emerged over whether new territories would adopt free or slave labour, sharpening regional divisions.

Northern settlers promoted free labour to protect economic opportunity.

Southern settlers expanded slavery westward to sustain plantation agriculture.

These competing visions laid groundwork for future national disputes.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Analyse the extent to which regional economic structures shaped contrasting attitudes toward slavery in the United States between the 1780s and early nineteenth century.

Question 1

1 mark for identifying a basic difference (e.g., the North increasingly adopted gradual emancipation while the South entrenched slavery).

1–2 additional marks for explaining the difference with supporting detail, such as:

Northern reliance on free labour economies encouraged antislavery policies.

Southern plantation agriculture strengthened commitment to slavery.

Northern states passed gradual emancipation laws; Southern states expanded slave codes.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which regional economic structures shaped contrasting attitudes toward slavery in the United States between the 1780s and early nineteenth century.

Question 2

Award marks based on the depth and accuracy of analysis.

1–2 marks for a basic statement that economic differences influenced attitudes (e.g., the free labour North versus the plantation South).

3–4 marks for developed explanation with supporting evidence, such as:

Northern commercial and early industrial economies reduced dependence on enslaved labour.

Southern cotton production, global demand, and plantation systems made slavery economically essential.

Regional migration patterns (e.g., movement of enslaved people into the Deep South) reinforced these divisions.

5–6 marks for well-structured analysis demonstrating clear links between economic structures and regional ideology, potentially including:

How economic interests shaped political actions and sectional identity.

Examples of how these attitudes influenced legislation or public discourse.

Recognition that these contrasts created long-term sectional tensions.