AP Syllabus focus:

‘After mid-18th-century imperial struggles, Britain imposed new taxes without colonial representation and asserted imperial authority, uniting colonists against restrictions on rights and trade.’

British attempts to raise revenue and reassert imperial control after the Seven Years’ War transformed colonial politics, provoking powerful debates about rights, representation, and authority across British America.

Britain’s Postwar Context and the Decision to Tax

The end of the Seven Years’ War left Britain with unprecedented global dominance but also an immense war debt and significant ongoing expenses to administer and defend its expanded empire. British officials believed that the North American colonies—whose security they had defended—should contribute to these costs. In their view, parliamentary sovereignty gave the central government unquestioned authority to legislate for the colonies, including raising revenue.

Imperial Logic Behind New Taxes

British policymakers, especially Prime Minister George Grenville, argued that colonial trade had long benefited from imperial protection yet remained lightly taxed. Asserting new taxes therefore seemed both reasonable and necessary to metropolitan leaders.

Britain sought a more rational, centralized system of imperial administration.

Officials aimed to stop widespread smuggling to enforce mercantilist principles, which held that colonies existed primarily to enrich the mother country.

The government believed that a standing army should remain in North America to stabilize relations with Native nations and deter European rivals.

A growing number of colonists saw these initiatives differently. The colonies had developed robust traditions of self-government, especially through elected assemblies controlling taxation. Many believed that these traditions were central to British liberty itself.

The Sugar Act and Early Resistance

In 1764, Parliament passed the Sugar Act, an updated and strengthened version of earlier trade laws. Although framed as a reform of customs regulations, its enforcement mechanisms made clear that revenue collection—not trade regulation—was now the priority.

Sugar Act: A 1764 parliamentary measure reducing the duty on imported molasses but increasing enforcement to raise revenue for the British Empire.

Colonial merchants objected strongly, arguing that new enforcement practices threatened economic autonomy. Admiralty courts without juries and intrusive customs searches alarmed many who believed their rights as British subjects were being violated.

The Stamp Act and Escalating Conflict

The crisis sharpened dramatically in 1765 with the Stamp Act, which required official, revenue-producing stamps on legal documents, newspapers, and numerous printed materials.

Stamp Act: A 1765 law imposing direct taxes on printed items in the colonies, marking Parliament’s first attempt at widespread internal taxation.

The Stamp Act directly affected a broad segment of colonial society—printers, lawyers, merchants, and ordinary consumers—which helped transform opposition from a merchant-led protest into a unified, cross-colonial movement.

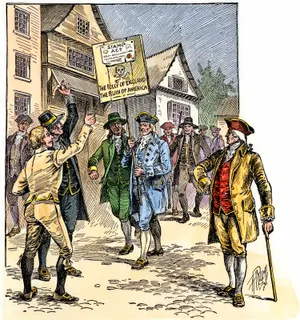

A hand-colored woodcut depicts a protest procession in New York opposing the Stamp Act, illustrating how new British taxes generated widespread public mobilization. The march highlights the spread of “no taxation without representation” as a popular rallying cry. Although the scene is specific to New York, it reflects broader colonial resistance across British America. Source.

Ideological Objections

Colonial leaders insisted that direct taxation without elected representation violated the fundamental principle of English liberty: that property could not be taken without consent.

“No taxation without representation” became a powerful slogan expressing a deep constitutional belief.

Colonists differentiated between external taxes (acceptable as trade regulation) and internal taxes (unacceptable without self-representation).

Parliamentary leaders rejected this distinction, asserting virtual representation, the idea that Parliament represented all British subjects regardless of voting rights.

Between these opposing views emerged a genuine constitutional crisis over the nature of empire.

New Imperial Enforcement and Growing Colonial Unity

British leaders simultaneously expanded enforcement using writs of assistance and new customs personnel. To the colonists, these measures appeared heavy-handed and arbitrary, confirming fears that imperial authority was shifting from consensual governance to coercion.

Organized Colonial Responses

Resistance broadened through coordinated political activity.

Stamp Act Congress (1765): Delegates from nine colonies met to articulate shared constitutional objections, marking one of the first major intercolonial political gatherings.

Committees of Correspondence: Networks that circulated information and built ideological cohesion.

Boycotts (Nonimportation Agreements): Merchants and consumers refused to purchase British goods, directly pressuring Parliament by targeting British manufacturers.

Popular protests: Groups such as the Sons of Liberty organized street demonstrations, sometimes destroying property of stamp distributors.

These efforts were notable for blending elite political argument with popular mobilization, creating a broader Patriot movement.

Popular protest: Crowds intimidated stamp distributors, organized demonstrations, and spread slogans like “no taxation without representation,” making resistance visible in streets, taverns, and print culture.

A creamware teapot inscribed “No Stamp Act” demonstrates how political resistance entered domestic spaces, turning everyday consumer goods into expressions of anti-tax sentiment. Manufactured in Britain for the American market, it commemorates the repeal of the Stamp Act. The additional decorative detailing goes beyond the AP syllabus but reinforces the connection between commerce, identity, and protest. Source.

The Declaratory Act and the Assertion of Authority

Although Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766 due to economic pressure and political turmoil, it simultaneously passed the Declaratory Act, reaffirming its right to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

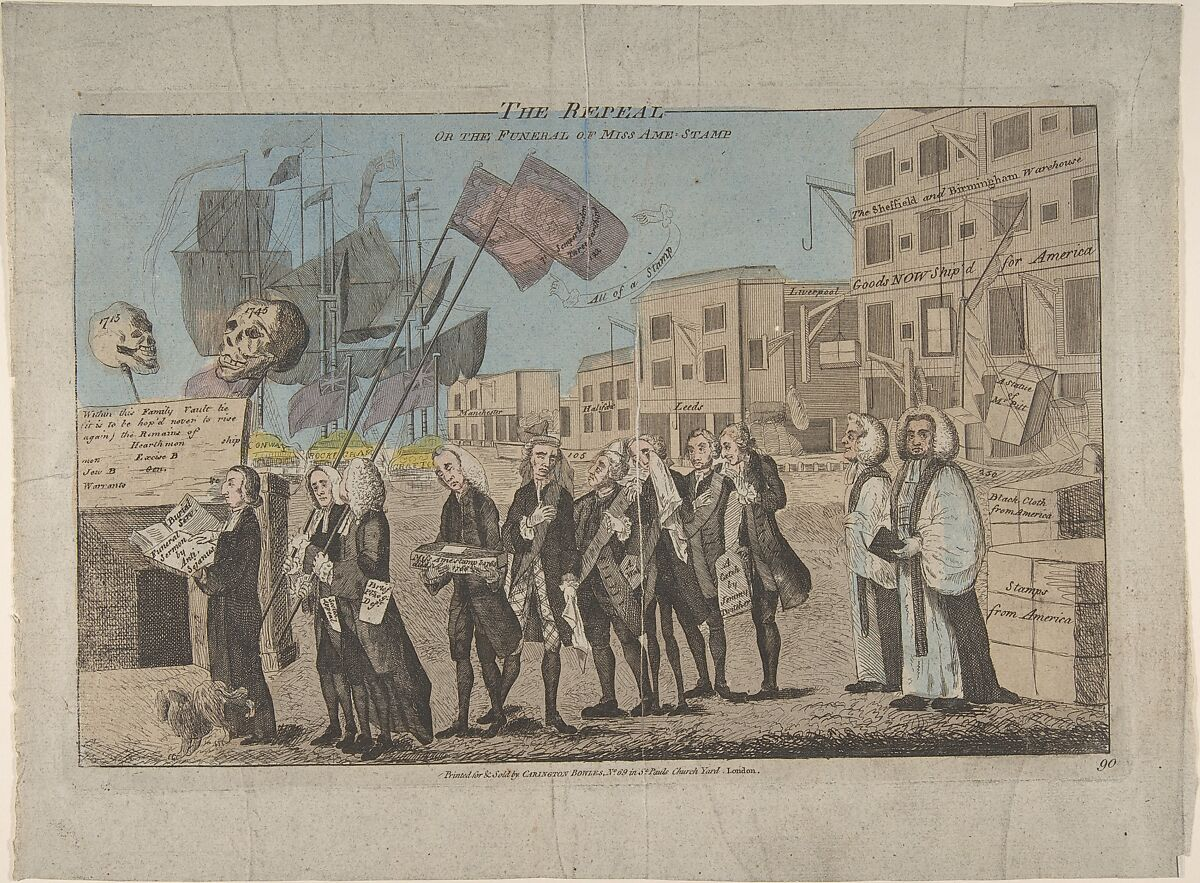

This satirical print shows British ministers conducting a mock funeral for the Stamp Act, symbolizing its repeal in 1766. The busy docks in the background emphasize the economic pressures created by colonial boycotts. While the image includes additional satirical details beyond the AP syllabus, it illustrates the tension between imperial authority and colonial resistance. Source.

Colonists celebrated the repeal but recognized that the larger constitutional dispute remained unresolved. The Declaratory Act implied that Britain would continue efforts to tighten imperial control.

The Townshend Duties and Renewed Crisis

In 1767, Parliament enacted the Townshend Acts, placing duties on imported goods such as glass, lead, paint, and tea. Although framed as external taxes, colonists recognized them as another attempt to raise revenue without consent.

Revenue funded colonial governors and judges, reducing assembly influence.

A reorganized Board of Customs Commissioners intensified enforcement and increased tensions in port cities.

Boycotts again became a central tool of protest, involving women prominently through the production of homespun textiles.

Toward Greater Intercolonial Cooperation

By the late 1760s and early 1770s, the shared experience of opposing new taxes forged stronger bonds among the colonies. While regional differences persisted, common grievances encouraged unity against imperial authority.

Newspapers spread arguments rooted in rights, liberties, and constitutional tradition.

Colonists believed Britain was restricting both economic opportunity and political autonomy.

Even moderate leaders grew wary of a pattern of imperial overreach.

The cumulative effect of new taxes, enforcement, and the assertion of imperial authority directly fostered a sense of colonial solidarity, setting the stage for more radical resistance as the imperial crisis deepened.

FAQ

British leaders argued that Parliament exercised full sovereignty over the empire and that colonists, like many Britons who could not vote, were protected through what they called virtual representation.

They contended that members of Parliament acted for the good of all British subjects, not merely for voters in their constituencies, and therefore colonial consent was not required for taxation.

Expanded customs enforcement made previously lax trade rules far stricter, creating friction in port towns.

Officials used writs of assistance to search warehouses and ships without specific warrants, undermining local legal traditions.

These practices reinforced the belief that Britain was imposing arbitrary authority and eroding traditional protections enjoyed by British subjects.

Elites initially opposed the taxes because they threatened legal and commercial interests, such as property rights and printed materials essential for professional work.

Ordinary labourers were more concerned with rising prices and disruptions to daily economic activity.

Unity grew when protests expanded beyond legal arguments to include boycotts, street demonstrations and shared slogans that resonated across social groups.

Newspapers, pamphlets and broadsides circulated rapidly among colonies, helping frame taxation as a constitutional crisis rather than a local dispute.

Printers played a central role by publishing critiques of British authority, often reprinting essays from other colonies, which spread common grievances and standardised arguments.

This shared political language helped align disparate colonial regions against imperial policies.

British merchants faced severe commercial losses when American boycotts reduced demand for manufactured goods.

Many petitioned Parliament, arguing that the economic damage outweighed any revenue gained from colonial taxes.

Their pressure contributed significantly to the repeal of the Stamp Act, though Parliament attempted to preserve its authority through the Declaratory Act, revealing tensions within British policymaking.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why many American colonists opposed the new taxes introduced by the British government after the Seven Years’ War.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why many American colonists opposed the new taxes introduced by the British government after the Seven Years’ War.

Mark allocation:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., lack of representation, violation of rights, economic burden).

1 additional mark for explaining why this reason generated opposition (e.g., how taxation without representation contradicted British constitutional principles).

1 additional mark for providing a specific example (e.g., Sugar Act or Stamp Act) that illustrates the reason.

Example of a 3-mark answer:

Colonists opposed the new taxes because they believed they were being taxed without representation in Parliament. This challenged their understanding of British liberty, which held that property could not be taken without consent. The Stamp Act of 1765 exemplified this grievance by imposing direct taxes on printed materials.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how British attempts to assert imperial authority between 1764 and 1767 contributed to increased unity among the American colonies. Refer to specific legislation and colonial responses in your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how British attempts to assert imperial authority between 1764 and 1767 contributed to increased unity among the American colonies. Refer to specific legislation and colonial responses.

Mark allocation:

1–2 marks for identifying relevant British actions (e.g., Sugar Act, Stamp Act, Townshend Duties, increased enforcement).

1–2 marks for explaining how colonial reactions developed (e.g., protests, nonimportation agreements, political cooperation).

1–2 marks for analysing how these actions and reactions promoted intercolonial unity (e.g., shared grievances, coordinated resistance, emergence of Congresses or committees).

To earn full marks, answers must demonstrate:

Clear understanding of the link between imperial authority and colonial unity.

Use of accurate, specific evidence.

Analytical connections showing how common experiences fostered cooperation.

Example of a 6-mark answer:

British efforts to tighten control after 1763, including the Sugar Act and the Stamp Act, directly challenged colonial expectations of self-government. These measures encouraged colonies to move beyond individual protests to coordinated responses. The Stamp Act Congress brought delegates together to articulate shared constitutional objections, while nonimportation agreements united merchants across regions. Increased enforcement and the continued assertion of parliamentary authority convinced many colonists that joint action was necessary, fostering a sense of common purpose that laid foundations for later collective resistance.