AP Syllabus focus:

‘Colonial leaders justified resistance by invoking the rights of British subjects and individuals, local traditions of self-rule, and Enlightenment ideas.’

American colonists drew on British legal traditions, individual rights, local self-government, and Enlightenment political theory to justify increasingly organized resistance to imperial authority. These ideological foundations shaped colonial unity and clarified why new taxes and regulations appeared illegitimate.

Origins of Ideological Resistance

British Constitutional Traditions

Colonial resistance emerged partly from the belief that colonists possessed the rights of British subjects, a term that referred to all individuals guaranteed legal protections under the English constitution. Colonists argued that these rights limited arbitrary government power, especially taxation without consent.

British subjects: People under British sovereignty who were entitled to historic English legal rights, including trial by jury and freedom from arbitrary taxation.

Colonists believed Parliament violated these rights through new imperial taxes and stricter enforcement measures. Their arguments rested on the idea that liberty required consent and representation, both central to British political culture.

This conviction blended constitutional precedent with local assumptions about political participation developed over many decades of colonial self-rule.

Local Traditions of Self-Government

Colonial assemblies had long exercised authority over taxation, militias, and domestic legislation. Many Americans viewed these institutions as guardians of community interests and as the legitimate origin of political authority in North America.

Colonists expected no taxation without representation, meaning only elected bodies could levy taxes.

Assemblies embodied popular sovereignty, the belief that government authority originates from the people.

Local governance contributed to a political culture in which imperial intervention appeared intrusive or unconstitutional.

Popular sovereignty: The principle that legitimate political authority is derived from the consent and collective will of the people.

Colonists therefore interpreted new imperial policies after 1763 as a direct threat to established practices of autonomy, reinforcing a shared sense that resistance was a defense of constitutional heritage rather than rebellion.

“The Repeal, or the Funeral of Miss Ame-Stamp” is a satirical engraving portraying the symbolic burial of the Stamp Act. It reflects transatlantic opposition to taxation without representation and the belief that such policies violated the rights of British subjects. Extra visual details, including caricatured British politicians, extend beyond syllabus needs but help contextualize political debate over rights and representation. Source.

Enlightenment Foundations of Colonial Arguments

Natural Rights Philosophy

Resistance leaders drew heavily on Enlightenment ideas, especially those associated with John Locke and other theorists who emphasized rationality, liberty, and the rights of individuals.

This title page from a 1690 edition of John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government highlights one of the most influential Enlightenment works shaping colonial thought. Locke’s arguments on natural rights and legitimate authority directly informed colonial claims that resistance was justified when government failed to protect liberty. The bibliographic detail shown exceeds syllabus requirements but reinforces the text’s historical authenticity. Source.

Individuals possessed natural rights, including life, liberty, and property.

Governments existed to protect these rights through a social contract, an implicit agreement between ruler and ruled.

If a government violated its contract, people retained the right to alter or abolish it.

Natural rights: Universal rights—such as life, liberty, and property—that individuals possess by virtue of being human and that governments must protect.

These ideas gave colonists an intellectual structure for criticizing British authority. They transformed specific grievances into broader claims about justice, legitimacy, and human freedom.

The Social Contract and Legitimate Authority

Enlightenment thinkers taught that rulers must govern through laws and institutions that reflect the consent of the governed. Colonists applied this logic to their criticisms of imperial policy.

Social contract: The Enlightenment concept that governmental authority arises from an agreement in which people consent to give power to rulers in exchange for protection of rights.

By the mid-1760s and 1770s, resistance leaders argued that Parliament violated the contract by imposing taxes without representation and restricting colonial economic freedom. They insisted that legitimate authority required consent, which Britain had ignored.

Voices and Texts That Shaped Ideological Resistance

Pamphlets, Newspapers, and Committees of Correspondence

Political writers and colonial assemblies spread ideological arguments widely. Pamphleteers described imperial policies as assaults on British liberty and explained why resistance aligned with constitutional and natural-law principles.

Key themes included:

The belief that standing armies in peacetime threatened liberty.

The warning that unchecked power would lead to tyranny, defined as oppressive rule exercised without the people’s consent.

The argument that vigilance was necessary to preserve rights.

Newspapers and town meetings circulated these ideas, strengthening colonial unity around shared ideological commitments.

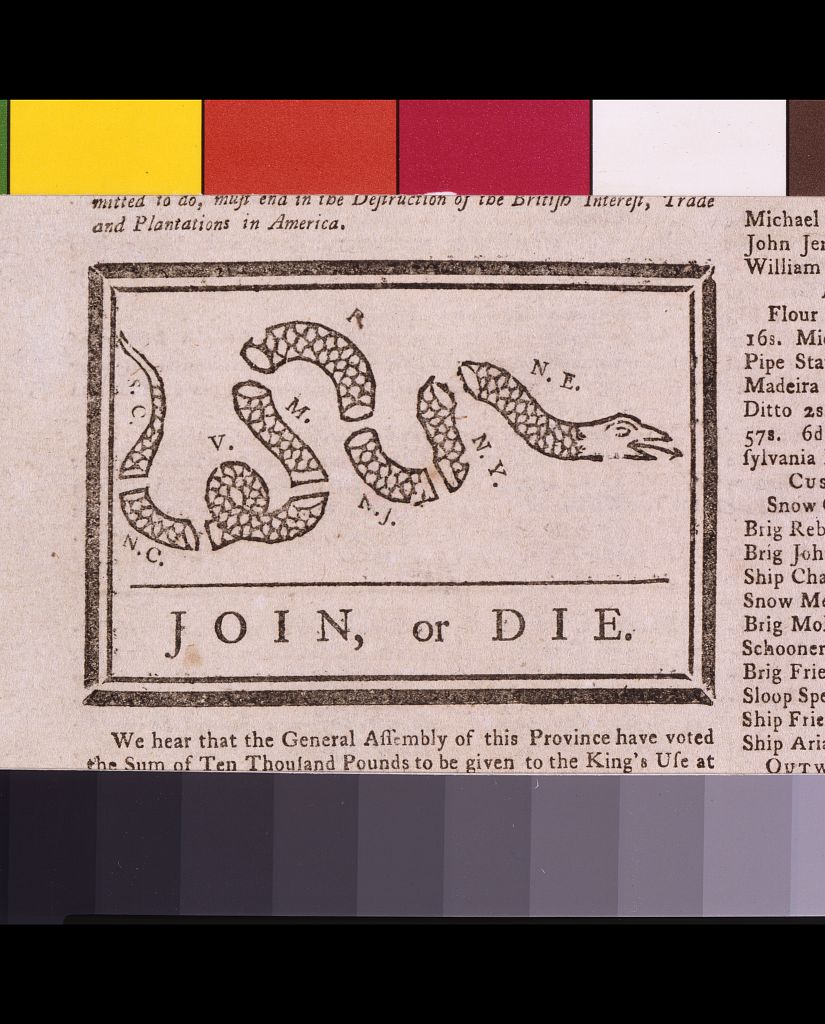

“Join, or Die,” attributed to Benjamin Franklin, illustrates the belief that only unified colonies could defend their liberties. Although originally published in 1754, it became a powerful symbol in later resistance movements. The image contains extra contextual symbolism not required by the syllabus but supports understanding of political messaging in the period. Source.

Influence of Colonial Intellectuals

Leaders such as James Otis, Samuel Adams, and Patrick Henry translated theory into political action. Their speeches and resolutions argued that all British subjects possessed identical rights and that taxation required representation.

Otis emphasized natural rights and denounced arbitrary governmental actions.

Adams framed resistance as a constitutional struggle to preserve inherited liberties.

Henry’s rhetoric connected liberty to moral responsibility and collective identity.

Their arguments depicted resistance not as sedition but as a necessary defense of political freedom.

The Ideological Logic of Resistance

Linking Rights to Political Action

Colonists believed resistance was justified because Britain violated both traditional and Enlightenment principles. They argued that:

Liberty depended on representation.

Property rights required consent before taxation.

Governments lost legitimacy when they ignored the people’s will.

Resistance was lawful when aimed at restoring constitutional balance.

These ideas united diverse colonial groups, transforming scattered protests into a coherent ideological movement. Through appeals to British rights, local self-government, and Enlightenment philosophy, colonial leaders developed a powerful intellectual case that framed resistance as both rational and necessary.

FAQ

Colonial lawyers played a key role by interpreting British constitutional principles in ways that emphasised limits on parliamentary power. Their pamphlets and court arguments often reframed local grievances as violations of long-standing legal rights.

They also helped popularise complex ideas—such as the distinction between internal and external taxation—making resistance appear grounded in legal precedent rather than rebellion.

Printing networks allowed ideas to circulate rapidly across colonies, creating shared ideological language. Printers reissued essays, letters, and pamphlets, helping unify resistance arguments.

They also standardised political vocabulary—terms like liberty, tyranny, and consent—ensuring colonists from different regions interpreted events through similar ideological frameworks.

Officials often believed Parliament held supreme authority over the empire, making colonial claims about rights or local autonomy appear misguided.

They also viewed the colonies as subordinate communities benefiting from imperial protection, leading them to argue that resistance was rooted in misunderstanding rather than constitutional principle.

Although not central to this subsubtopic, religious rhetoric sometimes reinforced Enlightenment themes by depicting liberty as part of a moral order.

Preachers often framed the defence of rights as a duty to future generations, providing a moral dimension that strengthened the logic of secular resistance arguments.

Elites tended to emphasise constitutional rights, property protections, and Enlightenment theory, reflecting their education and political influence.

Labourers and artisans often focused on practical concerns—fear of economic exploitation, threats to local autonomy, or anger at imperial enforcement—while still adopting the broader ideological language promoted by leaders.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Identify and briefly explain one Enlightenment idea that colonial leaders used to justify resistance to British authority in the 1760s and 1770s.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for correctly identifying a relevant Enlightenment idea (e.g., natural rights, social contract, consent of the governed).

1 mark for explaining the idea accurately (e.g., natural rights are inherent and must be protected).

1 mark for linking the idea to colonial resistance (e.g., colonists argued Britain violated these rights through taxation without representation).

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Explain how both British constitutional traditions and colonial political practices shaped ideological arguments for resistance against imperial authority in the years after 1763.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for explaining the belief that colonists held the rights of British subjects.

1 mark for describing how these rights limited arbitrary government and taxation.

1 mark for explaining colonial traditions of self-government (e.g., power of assemblies, local control over taxation).

1 mark for linking these traditions to expectations of political autonomy.

1 mark for explaining how the combination of constitutional rights and local practices made new imperial policies appear illegitimate.

1 mark for a coherent, historically grounded explanation connecting these elements to colonial resistance.