AP Syllabus focus:

‘The independence effort was energized by leaders such as Benjamin Franklin and by popular movements, including the political activism of laborers, artisans, and women.’

Grassroots activism and emerging Patriot leadership transformed the resistance movement by mobilizing ordinary people, broadening political participation, and empowering new voices that strengthened colonial unity against expanding British imperial authority.

Grassroots Activism and the Expanding Patriot Movement

Grassroots activism played a decisive role in shaping the independence effort, ensuring that resistance did not remain confined to elite political debates. Instead, ordinary colonists—laborers, artisans, sailors, farmers, and women—energized the movement through direct participation, expanding its scope and strengthening its legitimacy. Their activism helped translate ideological arguments into widespread collective action and sustained mobilization.

Committees, Crowds, and Community Mobilization

Across the colonies, popular political engagement grew through local committees and organized crowd actions. These bodies connected communities, enforced boycotts, and circulated political news.

Committees of Correspondence coordinated communication across towns, spreading information about British policies and rallying support for resistance.

Committee networks helped unify colonial responses and ensured that protests were not isolated local reactions.

Crowd-based actions, including marches and demonstrations, pressured colonial officials while signaling widespread dissatisfaction with imperial authority.

Local merchant and artisan groups enforced nonimportation agreements through social pressure and public shaming of violators.

These local practices fostered a sense of political participation that extended beyond traditional elites, embedding resistance into daily community life.

The Sons of Liberty and Artisan Leadership

The Sons of Liberty, an influential grassroots organization, mobilized laborers and artisans who played a powerful role in street-level resistance.

Its leadership drew heavily from urban tradespeople whose economic interests were directly threatened by imperial taxation.

Sons of Liberty: A colonial resistance organization that opposed British taxation through protests, coordination of boycotts, and the mobilization of popular support.

Artisan leaders guided the movement by framing imperial taxation as a direct threat to economic independence. They orchestrated symbolic actions, such as effigy burnings and mock funerals, to dramatize the stakes of resisting British authority.

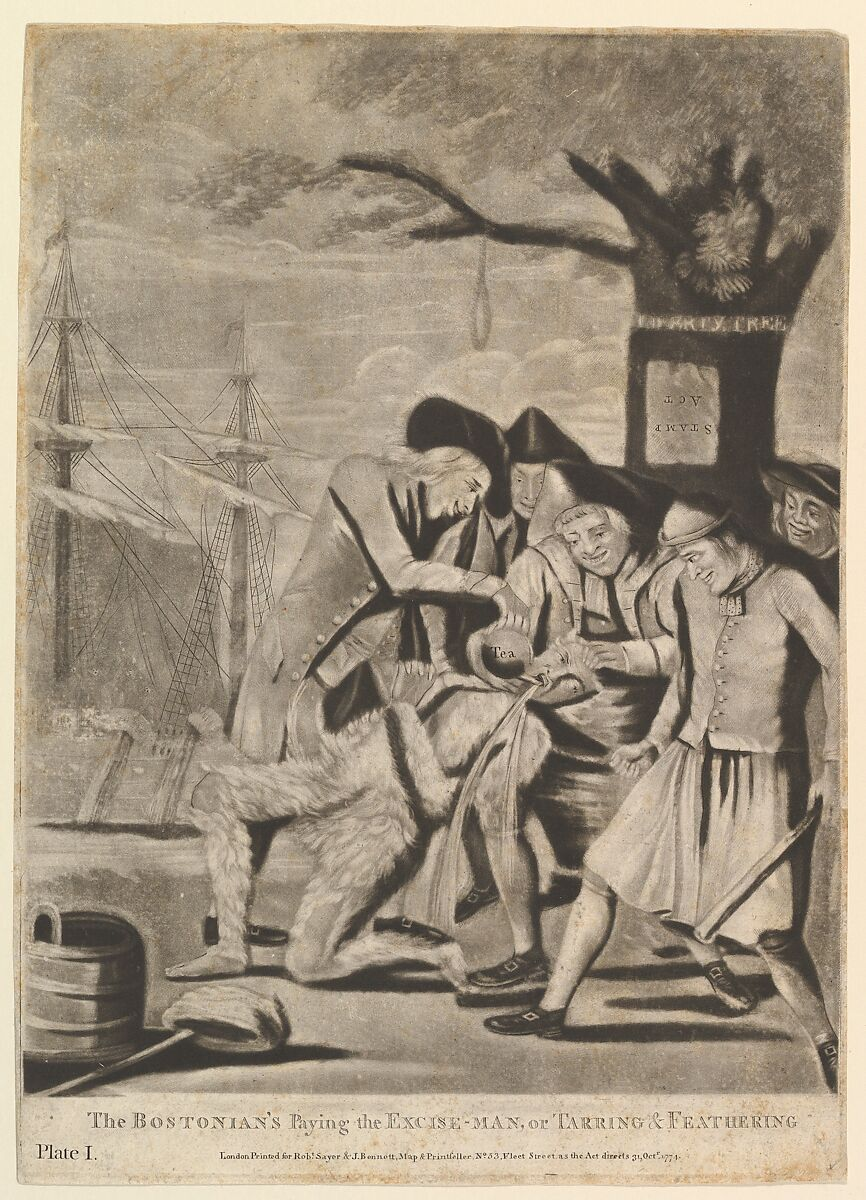

Mezzotint and etching from 1774 depicting a Boston crowd tarring and feathering customs officer John Malcom beneath the Liberty Tree. The print highlights how ordinary colonists used direct action and public humiliation to pressure imperial officials and reinforce nonimportation and protest campaigns. The image includes more violent detail than the study notes explicitly describe but remains an accurate historical example of radical grassroots activism. Source.

Benjamin Franklin and New Forms of Patriot Leadership

The AP syllabus highlights Benjamin Franklin as a key figure whose diplomatic skill and political messaging energized the independence movement.

Franklin bridged elite political negotiation and broad popular mobilization through:

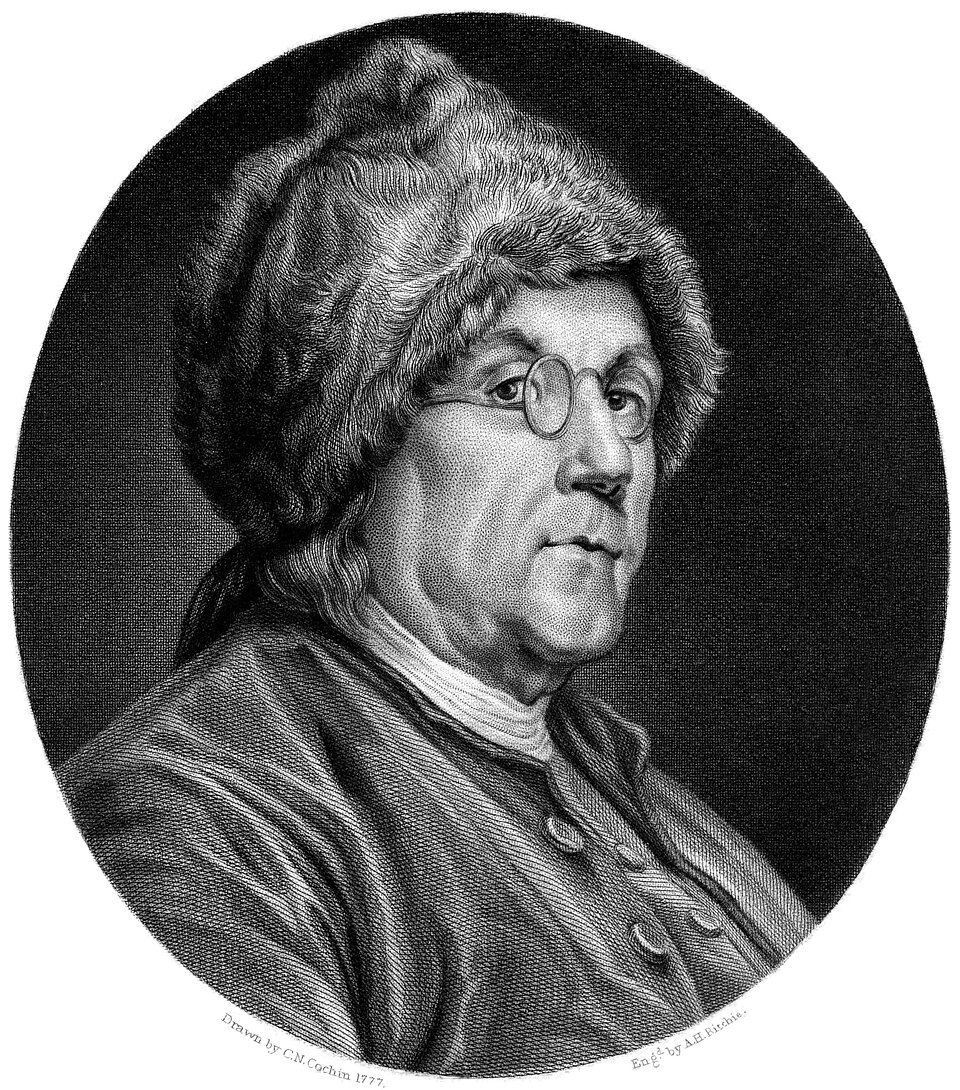

Engraving of Benjamin Franklin drawn by C. N. Cochin and engraved by A. H. Richie. Franklin’s composed posture and formal dress underscore his role as a leading Patriot intellectual and diplomat who helped channel popular discontent into coordinated political action. The image highlights his leadership rather than specific grassroots events. Source.

Advocacy for colonial unity during the era of imperial reforms

Persuasive writings that shaped public understandings of liberty and rights

Diplomatic efforts that later secured essential foreign support

His role exemplified new forms of leadership that emerged during escalating conflict: leaders who could articulate complex ideas while appealing to common colonial experiences.

Women and Political Mobilization

Women played a crucial role in sustaining the movement, particularly through economic activism and political expression. Their engagement demonstrated how resistance extended into domestic spaces and altered gendered expectations of political life.

Daughters of Liberty and Economic Protest

Women organized themselves into groups such as the Daughters of Liberty to support nonimportation and encourage self-sufficiency.

They produced homespun cloth to replace British textiles.

Illustration of a colonial woman spinning yarn while a young girl watches, representing the homespun movement encouraged by the Daughters of Liberty. Producing cloth at home helped replace British textiles and turned domestic work into an expression of political resistance. The image accurately reflects women’s economic contributions without depicting later roles not emphasized in this subtopic. Source.

They altered purchasing habits to align households with political goals.

Their public spinning gatherings symbolized communal resistance and economic independence.

Daughters of Liberty: Groups of colonial women who supported resistance to British authority by promoting nonimportation, producing homespun goods, and encouraging economic self-reliance.

A sentence to maintain separation between definition blocks.

Political Expression and Community Leadership

Women additionally shaped political culture through letter writing, petitioning, and organizing community discussions.

Though barred from formal political office, they influenced public opinion and modeled civic commitment. Their work strengthened the moral clarity of the Patriot cause and emphasized the universal stakes of resistance.

Laborers, Sailors, and Working-Class Protest

Urban working-class groups were central to street protests and to enforcing resistance policies. Sailors, dockworkers, and apprentices mobilized quickly, often forming the backbone of major demonstrations.

Their participation reflected economic grievances related to trade disruptions, taxation, and competition with British goods.

Their readiness for direct confrontation gave the movement energy and visibility.

Their involvement blurred social boundaries by making political resistance a cross-class effort.

These groups helped ensure that Patriot activism remained rooted in the lived experiences of ordinary colonists and not solely in elite rhetoric.

Popular Organizations and the Expansion of Political Participation

Popular mobilization encouraged experimentation with new organizational forms that expanded political participation.

Nonimportation Associations and Civic Enforcement

Nonimportation agreements required broad community adherence, and grassroots activists ensured compliance through:

Public monitoring of merchants

Social pressure campaigns

Community meetings that created new spaces for political voice

These associations modeled participatory governance, illustrating how colonial society could organize itself without direct imperial oversight. They implicitly prepared communities for more formal structures of self-government that would emerge later.

New Political Identities and the Patriot Cause

Grassroots activism and emerging leadership fostered a distinctly Patriot identity rooted in shared sacrifice, economic cooperation, and communal resolve. As more colonists participated in resistance, political identity became increasingly tied to collective action rather than passive loyalty.

The rise of new Patriot leaders—from artisans and women to figures like Benjamin Franklin—demonstrated how activism reshaped political culture. This blending of elite and popular leadership helped sustain the independence movement and solidified the broad support necessary for revolution.

FAQ

Urban centres such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia enabled rapid mobilisation because artisans, labourers, and sailors lived and worked in close proximity, making coordinated protests easier to organise.

In rural areas, activism relied more on committee networks, town meetings, and informal gatherings rather than large-scale street demonstrations.

Ports were especially significant because fluctuations in trade and customs enforcement directly affected labourers, increasing their participation in resistance activity.

Artisans’ economic independence and community visibility allowed them to mobilise neighbourhoods effectively. They often ran workshops or taverns that served as informal political hubs.

Key trades included printers, carpenters, blacksmiths, shipbuilders, and leatherworkers, all of whom had networks linking them to suppliers and clients.

Their craft-based associations could rapidly circulate information and enforce boycotts, giving artisans disproportionate political influence.

Yes, although many communities supported their efforts, women sometimes encountered criticism for engaging in what some viewed as male political roles.

However, their activism was typically framed as an extension of household responsibilities, helping reduce stigma.

Over time, public spinning gatherings and female-led boycotts gained legitimacy and even admiration as visible contributions to the resistance effort.

Enforcement varied but generally relied on social pressure rather than formal punishment.

Common methods included:

Public naming of merchants who violated agreements

Visits by committees to inspect inventories

Community-organised boycotts of offenders

Symbolic acts such as posting warning notices

These tactics contributed to widespread compliance without requiring centralised authority.

Crowd actions signalled broad public opposition, persuading some officials that enforcing imperial policies could provoke instability or threaten their position.

They also demonstrated that colonial elites could not ignore popular sentiment, pushing local governing bodies to adopt stronger resistance measures.

Additionally, repeated demonstrations helped create political cohesion by turning abstract grievances into shared public experiences.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which grassroots activism contributed to the expansion of the Patriot movement in the years leading up to the American Revolution.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks.

1 mark: Identifies a valid example of grassroots activism (e.g., nonimportation agreements, crowd actions, Daughters of Liberty).

2 marks: Provides accurate explanation of how this activism strengthened the Patriot movement (e.g., increasing public participation, enforcing boycotts, spreading information).

3 marks: Demonstrates clear understanding of impact by linking activism to broader unity or resistance (e.g., how committees or artisan leadership turned protests into a colony-wide movement).

(4–6 marks)

Analyse the role of new Patriot leaders, such as Benjamin Franklin, in shaping the political direction of the independence movement. In your answer, consider how leadership interacted with popular activism.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks.

1–2 marks: Identifies relevant Patriot leaders (e.g., Benjamin Franklin, artisan leaders, Sons of Liberty figures) and states their role.

3–4 marks: Provides accurate explanation of how leadership shaped political direction (e.g., articulating ideological messages, advocating unity, diplomacy, coordinating resistance).

5–6 marks: Offers a reasoned analysis connecting leadership with grassroots activism (e.g., how leaders transformed popular unrest into organised resistance, how elite and popular actions reinforced each other, or how figures like Franklin linked colonial grievances to broader principles).