AP Syllabus focus:

‘Enlightenment ideas encouraged American thinkers to emphasize individual talent over hereditary privilege and to rethink political authority and the relationship between people and government.’

Enlightenment thought reshaped colonial political culture by challenging inherited authority, elevating individual rights, and prompting Americans to reconsider the foundations of government, liberty, and legitimate power.

Enlightenment Context in the Atlantic World

During the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment—an intellectual movement that stressed reason, empirical inquiry, and human potential—circulated widely throughout Europe and the Americas. Colonial elites, printers, religious leaders, and political activists encountered the works of key European thinkers through newspapers, pamphlets, and transatlantic correspondence. Their ideas pressed Americans to question traditional hierarchies, particularly forms of hereditary privilege, which had long structured political and social life in both Britain and its colonies.

The movement emphasized that human beings possessed natural rights, meaning inherent rights that existed prior to the formation of governments. These rights could not legitimately be taken away by rulers or institutions. The assertion of natural rights provided colonists with a vocabulary for critiquing abuses of imperial authority and for envisioning alternative political structures.

Philosophical Foundations: Reason, Rights, and the Individual

Key Enlightenment Thinkers and Transatlantic Influence

American colonists drew heavily from European philosophers such as John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose writings questioned absolute monarchy and elevated the importance of individual agency.

John Locke argued that individuals possessed the natural rights of life, liberty, and property, and that governments existed to safeguard these rights.

Portrait of John Locke by Sir Godfrey Kneller, an English Enlightenment philosopher whose writings on natural rights and consent of the governed influenced American revolutionary thought. Locke’s argument that governments exist to protect individuals’ rights to life, liberty, and property provided a philosophical foundation for colonial resistance. The image reflects the intellectual authority later American thinkers drew on when rethinking political power and individual rights. Source.

Montesquieu promoted the idea of separating government powers to prevent tyranny.

Rousseau introduced the concept of the social contract, which held that governmental authority derived from the voluntary consent of the governed.

Natural rights: Rights inherent to all individuals by virtue of being human, not granted by governments and therefore not legitimately removable by rulers.

American colonists adapted these ideas to local conditions, linking Enlightenment reasoning with existing colonial traditions of self-rule and participatory politics. This fusion helped produce a distinctly American understanding of political legitimacy grounded in the sovereignty of the people rather than the Crown.

A sentence between definition blocks is required to ensure conceptual continuity and keep the notes readable.

Social contract: The theory that governments gain authority from the consent of the governed and must protect individuals’ rights or risk losing legitimacy.

Individual Talent and Challenges to Hereditary Privilege

A major Enlightenment theme adopted in the colonies was the celebration of individual talent. Enlightenment thinkers emphasized that ability, merit, and rational capacity—rather than lineage—should determine one’s place in society. This belief resonated strongly in a colonial world where economic mobility was more accessible than in Europe, yet political offices and social respect were still tied to elite families.

Colonial writers like Benjamin Franklin championed the notion of the self-made individual, promoting education, civic improvement, and personal initiative. These ideas contributed to emerging critiques of aristocracy and motivated calls for broader participation in public life. By the 1760s and 1770s, many colonists had come to view hereditary rule as incompatible with reason, justice, and the goals of a free society.

Rethinking Political Authority

Government as a Human Creation

Enlightenment philosophy reframed government as an institution created by people rather than a divine or hereditary order. This shift encouraged colonists to evaluate the British imperial system critically. If governments existed to protect rights, any government that violated those rights—including Parliament—could justifiably be resisted.

Key political implications emerged:

Legitimate authority derived from the people, not the monarchy.

Political power needed structural limitations to prevent abuse.

Citizens possessed the right—and perhaps the duty—to challenge unjust governance.

These principles did not immediately lead to calls for independence, but they laid the intellectual groundwork for rejecting parliamentary supremacy during the imperial crisis.

Liberty, Representation, and the Role of Reason

Colonists increasingly linked liberty to representation, drawing from Enlightenment reasoning to argue that taxation without representation was a violation of natural rights. Political pamphlets, lectures, sermons, and colonial assemblies frequently invoked these ideas to criticize imperial policy after 1763.

The Enlightenment also stressed the capacity of individuals to use reason to evaluate political claims. This emphasis reached a wide audience through print culture, expanding public debate and enabling ordinary citizens—not just elites—to participate in political discussions. Such engagement helped democratize political life and paved the way for broader ideological commitment to the Revolutionary movement.

Enlightenment Ideals in Emerging American Political Culture

Written Constitutions and Rights Protections

As tensions with Britain intensified, Enlightenment principles informed early American experiments with government. Colonies-turned-states drafted written constitutions, articulating political authority in precise, public documents. These constitutions frequently included declarations of rights, protecting freedoms such as speech, press, religion, and due process. The transition toward written frameworks reflected Enlightenment commitments to clarity, rational organization, and limitations on governmental authority.

Citizenship and Civic Responsibility

Enlightenment thought also reshaped ideas of citizenship. Instead of subjects obedient to a monarch, Americans increasingly imagined themselves as free citizens participating in a republic founded on reason and mutual consent. This shift elevated expectations for civic virtue, public deliberation, and active engagement in political life.

The Enduring Legacy

By the eve of the Revolution, Enlightenment ideas had become central to American political identity. They shaped colonists’ critiques of British policy, informed the language of revolutionary documents, and guided the design of new governmental structures. The subsubtopic’s emphasis on individual talent over hereditary privilege and on reevaluating political authority captures how deeply these ideas transformed American understandings of rights, government, and the relationship between individuals and the state.

Portrait of Baron de Montesquieu, a French Enlightenment thinker whose work argued that political power should be divided among separate branches. His theory of separating legislative, executive, and judicial authority deeply influenced American constitutional design. The image focuses on Montesquieu himself; it does not depict the branches of government, but anchors the key figure behind the concept. Source.

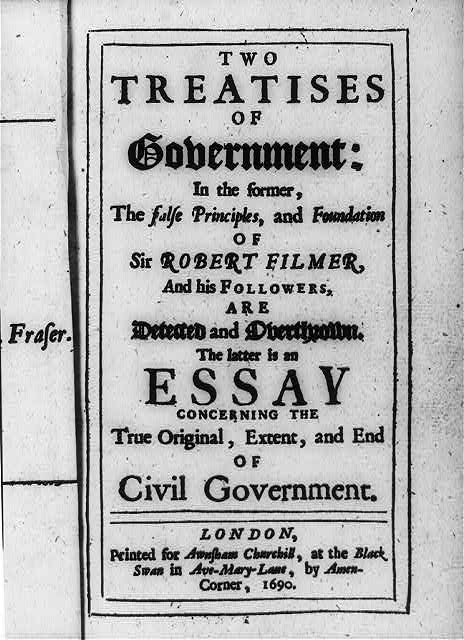

Title page of John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1690), a foundational Enlightenment work arguing that legitimate government rests on the consent of the governed and exists to protect individuals’ natural rights. American revolutionaries drew heavily on these arguments when challenging monarchical authority and redefining political power. The page includes bibliographic references that extend beyond AP requirements but help contextualize the work historically. Source.

FAQ

Enlightenment ideas circulated not only among elite intellectuals but also through sermons, town meetings, newspapers and local debating societies.

Print culture expanded rapidly, allowing essays and pamphlets inspired by Enlightenment writers to reach rural communities.

Many colonists encountered simplified explanations of natural rights, representation and government by consent through ministers who incorporated Enlightenment reasoning into religious instruction.

This diffusion meant that complex philosophical concepts became part of everyday political conversation rather than ideas limited to urban elites.

The Enlightenment encouraged the belief that education developed reason, moral judgement and civic virtue.

As a result, colonists increasingly viewed literacy and schooling as essential for responsible citizenship.

• New academies and libraries were founded to promote self-improvement.

• Scientific societies and lecture series flourished, especially in port cities.

This strengthened the idea that political participation should be informed by knowledge rather than inherited status.

Unlike Britain, the colonies lacked a deeply entrenched aristocracy, making Enlightenment attacks on hereditary power resonate more strongly.

Colonial society already rewarded commercial success, skill and local reputation, which aligned with Enlightenment arguments for merit over lineage.

These conditions made colonists more receptive to political systems based on consent and rational governance rather than royal prerogative.

Enlightenment writers often argued that humans were capable of reason and moral decision-making, challenging older beliefs that people required strong, inherited authority to control their impulses.

Colonists who embraced this view believed that citizens could participate responsibly in shaping government.

This underpinned support for written constitutions, elective offices and civic responsibility, as governance was seen as a human-made system that could be improved through rational design.

The scientific method encouraged observation, experimentation and scepticism toward traditional explanations.

Colonists applied these habits of mind to politics:

• They questioned long-standing political hierarchies.

• They evaluated government performance through evidence and practical outcomes.

• They believed political systems could be redesigned, just as scientific theories could be refined.

This approach supported the idea that society and government should evolve based on reason rather than custom or inherited authority.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Explain one way in which Enlightenment ideas influenced American colonists’ views of legitimate government in the period before the American Revolution.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying an Enlightenment idea (e.g., natural rights, social contract, separation of powers).

1 mark for describing how this idea challenged traditional authority or hereditary privilege.

1 mark for explaining how it shaped colonists’ beliefs about government (e.g., that authority derives from the people, governments must protect rights, resistance is justified if rights are violated).

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Analyse how Enlightenment emphasis on individual talent and merit, rather than hereditary privilege, contributed to emerging debates about political authority in the American colonies.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing the Enlightenment emphasis on individual talent or merit.

1 mark for explaining how this challenged Old World assumptions about inherited status or aristocratic governance.

1 mark for linking these ideas to broader colonial political culture (e.g., traditions of self-government, civic participation).

1 mark for explaining how Enlightenment ideals encouraged colonists to question the legitimacy of British rule.

1 mark for showing how these ideas informed critiques of monarchy and demands for forms of government based on consent.

1 mark for a developed, coherent explanation connecting Enlightenment principles to pre-revolutionary political debates.