AP Syllabus focus:

‘Religious belief strengthened many Americans’ sense that they were a people blessed with liberty, reinforcing revolutionary arguments about freedom and moral purpose.’

Religious convictions in the American colonies helped redefine political identity, encouraging many colonists to interpret liberty as both a divine blessing and a moral responsibility during the Revolution.

Religion and Revolutionary Political Culture

Religion played a significant role in shaping how colonists understood liberty, authority, and moral obligation during the years leading to the American Revolution. Sermons, religious publications, and congregational gatherings encouraged many Americans to see political events through a spiritual and ethical lens. This religious framing did not replace Enlightenment reasoning; rather, it blended with it, reinforcing the belief that liberty was sacred and that resistance to tyranny aligned with both divine law and natural rights.

The Influence of Protestant Traditions

The dominant Protestant culture in the colonies, especially within Puritan-descended New England communities, cultivated a worldview emphasizing personal conscience, communal responsibility, and vigilance against corruption. These traditions shaped colonists’ readiness to interpret British policies after 1763 as threats not only to political autonomy but also to their religious and moral order.

Conscience: The inner sense of moral right and wrong that guides individual judgment.

Many colonists believed that violating conscience—such as by submitting to perceived tyranny—would endanger both personal virtue and the health of the community. This belief gave religious weight to political resistance.

Sermons known as “election sermons” and “jeremiads” urged listeners to guard against moral decline and resist leaders who violated God’s principles. These messages resonated strongly in an era of rising tensions with Britain.

The Great Awakening’s Long-Term Impact

Although the First Great Awakening occurred decades earlier, its legacy remained influential during the revolutionary period.

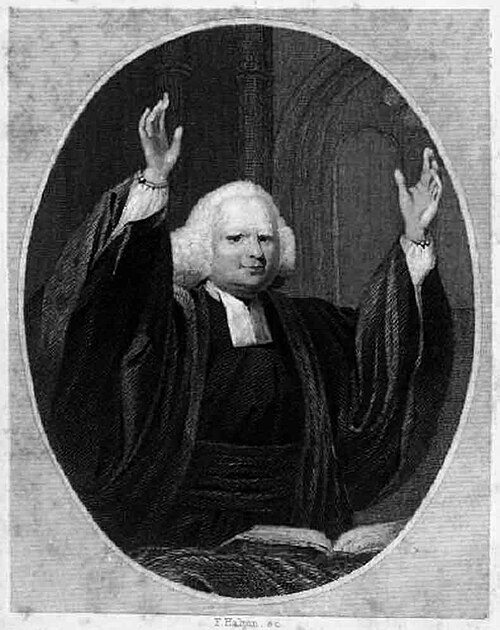

Engraving of George Whitefield, a leading Great Awakening preacher, delivering a sermon with uplifted hands from a church pulpit. His dramatic style and emphasis on individual spiritual experience helped normalize questioning traditional authority, reinforcing colonial arguments for political liberty. The image includes church interior details that exceed syllabus requirements but help students visualize 18th-century Protestant preaching environments. Source.

Its emphasis on individual spiritual experience, skepticism toward established authority, and moral self-governance reinforced revolutionary thinking.

Key influences included:

A focus on individual transformation that paralleled political calls for self-rule.

The elevation of ordinary people’s spiritual authority, encouraging broader political participation.

A culture of questioning traditional hierarchies, making colonists more receptive to challenging British imperial authority.

These currents strengthened a belief that moral and political authority ultimately rested with the people, not distant rulers.

The Language of Liberty in Religious Discourse

Religious rhetoric helped popularize the idea that liberty was God-given and that protecting it was a sacred duty. Ministers often linked biblical narratives—such as the Israelites’ escape from Egypt—to the colonists’ struggles. This made political resistance emotionally powerful and morally urgent.

Liberty as a Divine Blessing

Many colonists believed that their society had been specially blessed with freedom and moral purpose. This belief drew from both biblical imagery and longstanding Protestant fears of corruption. Religious preaching framed liberty not simply as a political preference but as a divine trust requiring active protection.

Moral purpose: A sense of ethical mission guiding individual or collective actions.

The idea of moral purpose encouraged colonists to view resistance as a righteous duty. It also helped unify diverse communities, since defending liberty was portrayed as defending God’s plan for the colonies.

Religious Arguments Against Tyranny

Clergy frequently warned that unchecked power threatened both spiritual and civic well-being. Sermons cited the dangers of “corruption,” “idolatry,” and “tyranny,” presenting British policies such as taxation without representation as signs of moral decay.

Religious arguments against tyranny often relied on:

Biblical warnings against unjust rulers

Covenant theology, which emphasized mutual accountability between people and government

The belief that God favored societies committed to justice and liberty

This fusion of theology and politics made resistance appear not only justified but necessary to preserve a godly society.

Religion and Revolutionary Mobilization

Religious leaders played a practical role in sustaining colonial resistance. Churches served as meeting places, communication networks, and centers for distributing political ideas.

Interior of an 18th-century colonial meetinghouse with wooden box pews, galleries, and a central pulpit, similar to those used in New England during the revolutionary era. Such spaces served both religious and civic purposes, enabling sermons about virtue and justice to merge with debates over British authority. Architectural details extend beyond syllabus content but help students imagine how religion and politics shared the same physical environment. Source.

Ministers read official proclamations, organized community action, and encouraged enlistment in the Patriot cause.

Patriot Ministers and Public Opinion

Many Patriot ministers argued that defending rights aligned with Christian teaching. Their influence extended across social classes and geographic regions, helping spread revolutionary ideals.

Important characteristics of Patriot religious leadership included:

Moral framing of political events

Calls for vigilance against oppression

Encouragement of sacrifice for the common good

Condemnation of British actions as threats to divine principles

This religious messaging made complex political debates understandable and compelling for ordinary colonists, helping sustain support for resistance.

Religious Community Life as a Source of Unity

Church communities fostered networks of cooperation and collective identity that proved crucial during the revolutionary movement. Shared worship, mutual aid, and participation in congregational governance helped Americans imagine themselves as part of a larger moral and political community.

Many colonists came to see the defense of liberty as part of their religious duty to family, congregation, and society. This sense of shared responsibility knitted together political ideals, religious commitment, and daily life in ways that deeply influenced the revolution’s ideological foundation.

Religion’s Lasting Influence on American Political Identity

Religion’s contribution to the language of liberty helped create a durable American political culture grounded in moral obligation, vigilance against tyranny, and the belief that freedom has both civic and spiritual dimensions. These ideas persisted long after independence, shaping debates about rights, governance, and national purpose in the new republic.

FAQ

Congregationalist and Presbyterian ministers were most outspoken in linking liberty with divine purpose, partly because their theological traditions emphasised covenantal responsibility and resistance to corruption.

Anglican clergy were more divided; many Loyalist-leaning ministers avoided revolutionary rhetoric, while some low-church Anglicans adopted liberty language influenced by evangelical revivalism.

Baptists and other dissenting groups often embraced liberty discourse to challenge established churches, integrating religious freedom with broader political claims.

The colonial population was steeped in biblical literacy, making scriptural references immediately meaningful.

Stories such as the Israelites’ escape from Egypt echoed colonial fears of arbitrary authority and oppression.

Ministers used these narratives to create emotional parallels:

Pharaoh represented corrupt monarchy

The Promised Land symbolised a future of political and moral self-rule

This made political arguments feel both familiar and morally compelling.

Yes, but in contrasting ways. Loyalist clergy often argued that scripture required obedience to established authority, warning that rebellion risked moral disorder.

Patriot ministers countered with covenant theology, asserting that rulers who violated divine or natural law forfeited obedience.

These competing interpretations show that religious discourse was not uniformly Patriot; it formed a contested arena shaping both sides’ moral reasoning.

Pamphlets, sermon reprints, and religious newspapers helped distribute revolutionary religious language widely.

Key effects included:

Allowing rural communities to access influential sermons preached in urban centres

Enabling clergy to reach audiences beyond their congregations

Reinforcing shared moral vocabulary that framed resistance as righteous

Religious print networks often moved faster and more broadly than political newspapers alone.

Women participated by interpreting sermons, hosting religious gatherings, and embedding liberty rhetoric into household religious practices.

Their engagement included:

Teaching children that liberty was both a spiritual blessing and a civic responsibility

Supporting ministers and meetinghouse activities

Using religious arguments to justify household economies of sacrifice for the Patriot cause

While not formal political actors, women helped sustain the moral foundation of revolutionary ideology within families and communities.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which religious belief contributed to colonial arguments for liberty in the period leading up to the American Revolution.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid religious influence on colonial ideas about liberty (e.g., belief that liberty was God-given).

• 2 marks: Provides a basic explanation of how religious belief strengthened arguments for resistance.

• 3 marks: Offers a clear and accurate explanation linking religious belief to political action or ideological commitment (e.g., sermons portraying resistance as a moral duty).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1754–1800, analyse how religious language and institutions shaped political mobilisation and support for resistance against Britain. In your answer, refer to specific examples of religious discourse, leadership, or community practices.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 1–2 marks: Identifies examples of religious language, institutions, or leaders influencing colonial political culture.

• 3–4 marks: Provides a partial analysis explaining how these religious elements supported mobilisation or shaped resistance.

• 5–6 marks: Offers a well-developed analysis with specific evidence (e.g., election sermons, Great Awakening legacy, role of meetinghouses), showing how religious discourse and institutions reinforced ideas of liberty, civic duty, and resistance to perceived tyranny.