AP Syllabus focus:

‘The new framework separated powers among three branches of government, aiming to prevent tyranny by dividing and checking authority.’

The Constitution established a system that dispersed governmental authority across three distinct branches, ensuring no single institution could dominate and creating a structure designed to safeguard liberty through balanced, interdependent powers.

The Constitutional Logic Behind Separation of Powers

The framers sought to prevent the concentration of authority that had characterized British imperial rule. By distributing power among three branches—legislative, executive, and judicial—the new system aimed to create a limited yet dynamic central government.

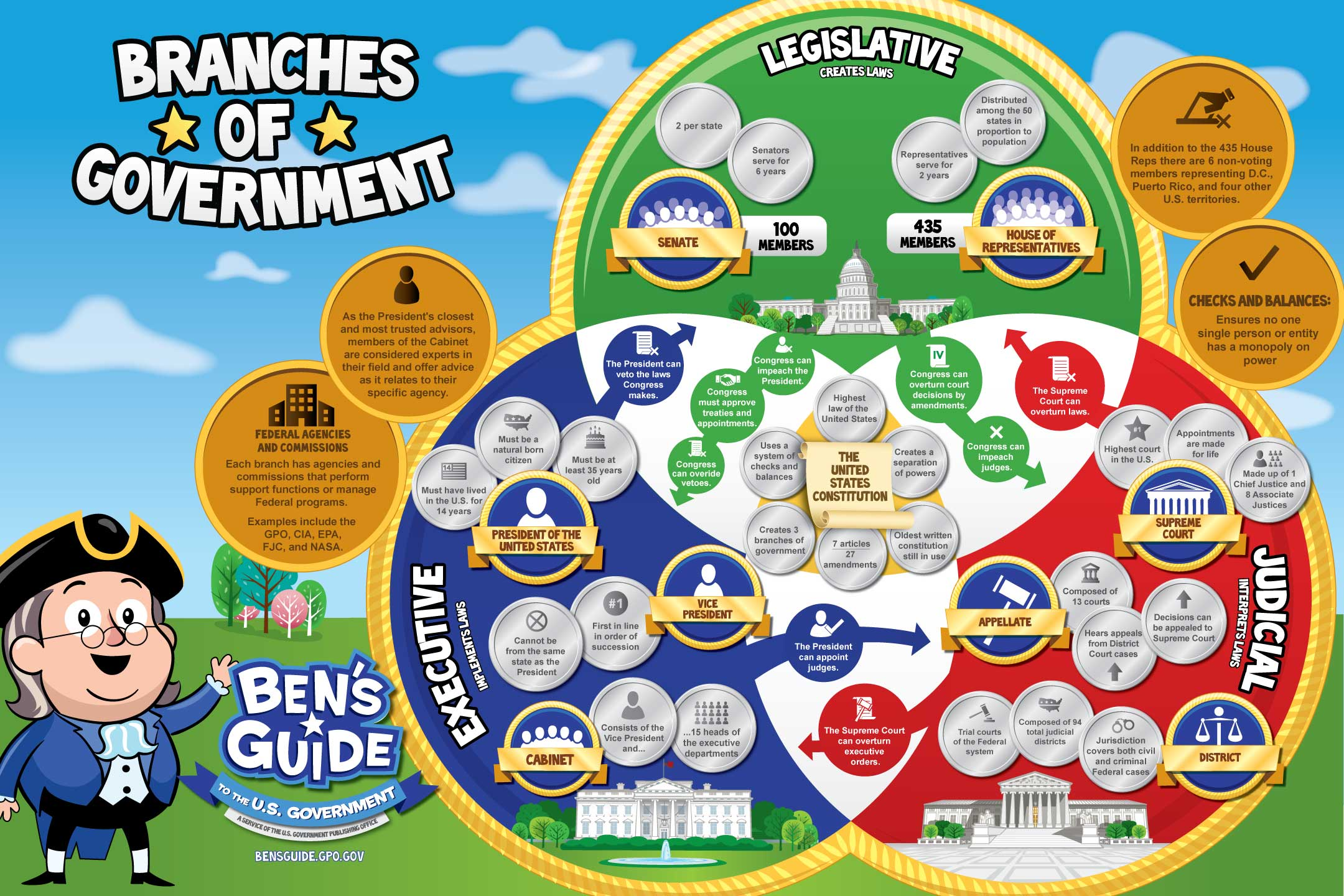

This infographic illustrates the three branches of the U.S. government, summarizing the main role of each branch in making, enforcing, and interpreting laws. It visually reinforces how power is divided so that no single branch dominates. The graphic includes brief examples of each branch’s duties, some of which extend slightly beyond the content of these notes but remain aligned with AP U.S. History foundations. Source.

Each branch gained distinct functions, while mechanisms of checks and balances ensured ongoing oversight and accountability. This framework reflected Enlightenment influences, colonial experience, and fears of both tyranny and governmental weakness.

Key Principles Embedded in the System

Division of governmental functions into lawmaking, law-executing, and law-interpreting responsibilities

Mutual oversight, enabling each branch to limit potential abuses by the others

Institutional independence, including separate elections, terms, and constituencies

Shared powers in areas like war, appointments, and law enforcement to encourage compromise

The Legislative Branch: Lawmaking and Representative Authority

The Constitution vested lawmaking power in the bicameral Congress, composed of the House of Representatives and the Senate. This structure balanced population-based representation with state equality and ensured slower, more deliberate policymaking.

Core Responsibilities of Congress

Drafting and passing legislation

Controlling taxation and federal spending

Declaring war and overseeing the military budget

Approving treaties and presidential appointments (Senate)

Investigating governmental actions and maintaining oversight

Checks on the Executive included impeachment powers, budgetary authority, and confirmation of appointments, while checks on the Judiciary involved determining court structures and approving judicial nominees.

The Executive Branch: Enforcement, Leadership, and National Administration

The president, elected independently of Congress, became responsible for executing federal law and directing national policy. The framers intentionally designed the presidency with both energy and constraint to avoid the rise of monarchical power.

Main Executive Powers

Enforcing federal laws through departments and agencies

Acting as commander in chief of the armed forces

Negotiating treaties and conducting diplomacy

Appointing federal judges, ambassadors, and executive officials

Issuing vetoes to block or influence congressional legislation

Veto: The constitutional power of the president to reject a bill passed by Congress, preventing it from becoming law unless overridden.

The executive remained limited because many of its major actions—such as treaties, appointments, and war decisions—required legislative approval or oversight.

The Judicial Branch: Constitutional Interpretation and Legal Review

The Constitution established a Supreme Court and allowed Congress to create lower federal courts. Judges served during good behavior, granting independence from political pressure and enabling long-term constitutional interpretation.

Judicial Responsibilities

Interpreting federal laws and the Constitution

Resolving disputes involving states, treaties, and federal officials

Reviewing the legality of executive and legislative actions

Ensuring uniform application of national law

Although judicial review was not explicitly stated in the Constitution, the structure implied that courts would act as a safeguard against unconstitutional actions.

Judicial Review: The authority of courts to determine whether laws or governmental actions violate the Constitution.

The judiciary maintained checks on the other branches while itself being constrained by appointments, potential impeachment, and the inability to enforce its own decisions without executive cooperation.

Interactions Among the Three Branches

The framers’ design created constant interaction and negotiation. Each branch shared certain powers yet retained exclusive functions, producing a balanced system that relied on cooperation and conflict.

Examples of Interbranch Dynamics

Legislation: Congress drafts laws, the president signs or vetoes them, and courts interpret them.

Appointments: The president nominates officials, the Senate confirms them, and courts review their actions.

War powers: Congress declares war and funds the military, while the president directs operations.

These intertwined responsibilities ensured that no single branch could unilaterally shape national policy without encountering limits or requiring consent from another part of the government.

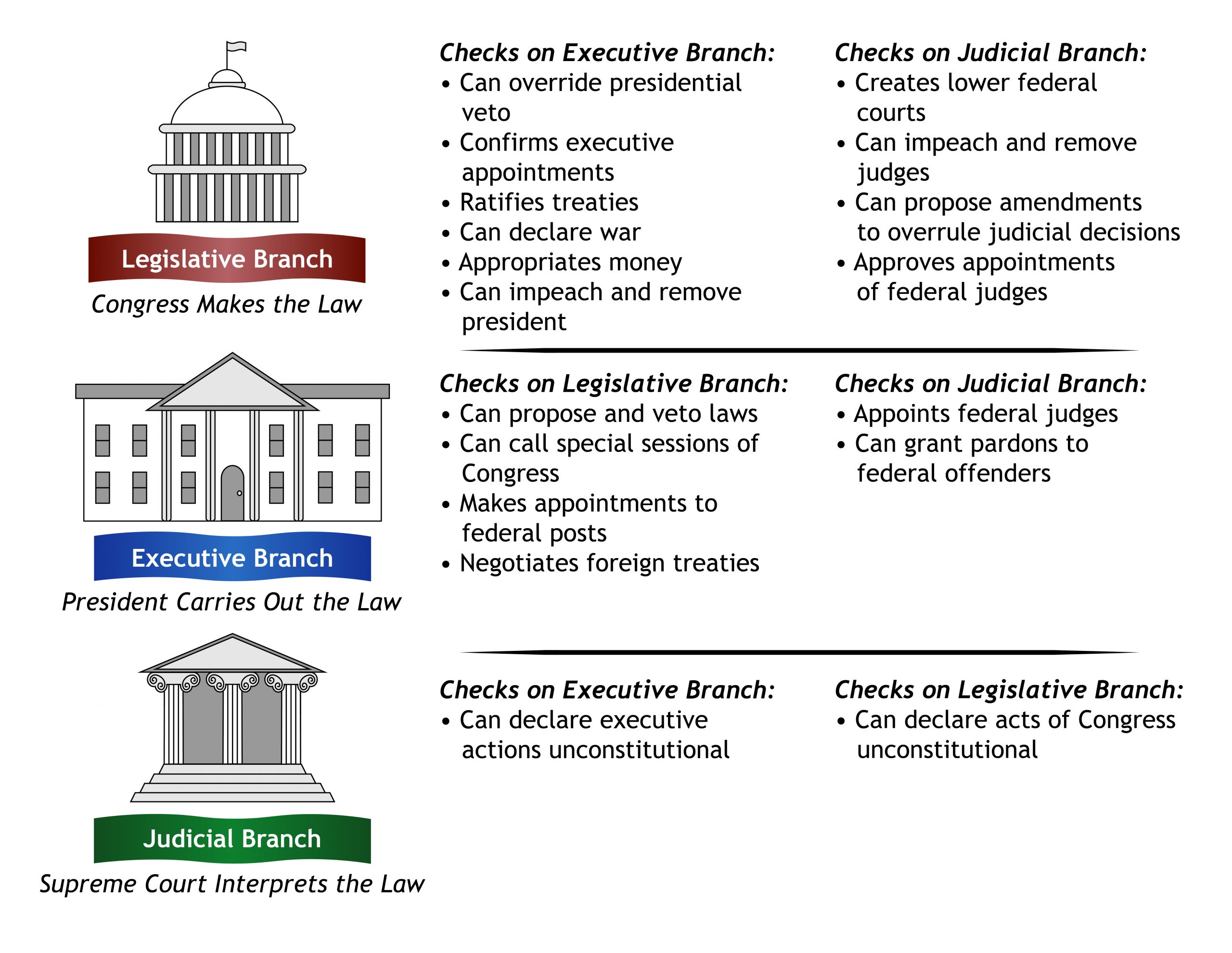

This diagram maps the key checks each branch exercises over the others, such as vetoes, judicial invalidation of laws, and Senate confirmations. It visualizes the interbranch constraints discussed in these notes, showing how authority is balanced across institutions. Some examples included extend slightly beyond the precise AP U.S. History requirements but remain helpful for conceptual understanding. Source.

Preventing Tyranny Through Checks and Balances

To maintain republican liberty, the Constitution embedded a layered system of mutual restraints. Important mechanisms included:

Structural Safeguards

Separate elections for the president and Congress

Staggered Senate terms to encourage stability

Lifetime judicial tenure to ensure independence

Procedural Safeguards

Impeachment of executive and judicial officials

Overriding vetoes through a two-thirds congressional vote

Judicial invalidation of unconstitutional laws or actions

Through this design, the Constitution established a central government capable of governing effectively while protecting against the concentration of power, fulfilling the framers’ aim of balancing authority in the early republic.

FAQ

The framers drew heavily on Enlightenment ideas, especially Montesquieu’s argument that separating lawmaking, law-enforcing, and law-interpreting functions created more stable government.

They also looked to colonial experiences. Governors, assemblies, and courts had historically clashed, giving delegates practical examples of how powers might be distributed.

Debates at the Constitutional Convention refined this further, with delegates assigning powers based on which body they believed could exercise them most responsibly and with the fewest risks of abuse.

The framers believed the nation needed a single executive who could respond quickly to crises, conduct foreign policy effectively, and provide unified administrative leadership.

At the same time, they feared the emergence of a monarch-like figure. To prevent this, they placed the president under legislative oversight, limited term length, and required Senate approval for major actions such as treaties and appointments.

This combination aimed to ensure decisiveness without enabling authoritarian rule.

Lifetime tenure was designed to insulate judges from political pressure, ensuring that decisions would be based on constitutional principles rather than shifting public opinion or partisan influence.

Additionally, the framers believed stability in the judiciary would help create consistent interpretations of federal law over time.

The decision reflected their belief that courts must be independent if they are to act as a meaningful check on the legislative and executive branches.

Reactions varied. Supporters argued that co-equal branches protected liberty and prevented the concentration of power familiar from British rule.

Sceptics worried that the structure was either too weak or too strong:

Some feared the president resembled a monarch.

Others believed Congress might dominate because it controlled lawmaking and finance.

A few questioned whether courts should have authority to interpret the Constitution at all.

These debates influenced early party divisions and constitutional interpretation.

As the new system was tested, disagreements emerged over how far each branch should extend its authority.

Conflicts included:

Disputes over executive power during foreign policy crises.

Tensions between Congress and the president over appointments and legislation.

Early debates about the legitimacy and scope of judicial review.

These struggles were not signs of failure but part of the system’s design, forcing branches to negotiate boundaries and preventing unchecked dominance by any one of them.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the separation of powers in the United States Constitution was intended to prevent tyranny.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a relevant feature of separation of powers (e.g., dividing authority among three branches).

1 mark for explaining how this feature limits the concentration of power.

1 mark for linking the design to preventing tyranny or abuses of authority.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the system of checks and balances shaped the relationship between the legislative and executive branches in the early United States. Provide specific examples to support your argument.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying the principle of checks and balances.

1 mark for describing a power held by Congress that checks the executive (e.g., impeachment, overriding vetoes, confirmation of appointments).

1 mark for describing a power held by the president that checks Congress (e.g., veto power).

1 mark for explaining how these checks influenced early political interactions or conflicts.

1 mark for using at least one historically appropriate example from the constitutional framework or early federal government.

1 mark for a coherent analytical explanation of how the relationship between the branches reflected the broader constitutional aim of preventing abuses of power.