AP Syllabus focus:

‘Ratification marked a shift from a weak confederation to stronger national institutions, while continuing earlier concerns about protecting liberty and limiting centralized power.’

The transition from the Articles of Confederation to the U.S. Constitution revealed both enduring political concerns and major structural changes, reshaping national authority while preserving core commitments to liberty.

Continuity and Change from the Articles

Structural Weaknesses Under the Articles

The Articles of Confederation created the first national framework for the United States after independence, but its institutional structure reflected deep fears of centralized authority. Under the Articles, Congress served as the sole national institution, and states retained most governing power. This arrangement left the national government weak, decentralized, and financially unstable, as Congress lacked the authority to levy taxes, regulate interstate commerce, or enforce its own laws without state cooperation.

The transition from the Articles of Confederation to the U.S. Constitution revealed both enduring political concerns and major structural changes, reshaping national authority while preserving core commitments to liberty.

This painting, “Signing of the Constitution,” depicts delegates in Independence Hall on September 17, 1787, adopting the new Constitution. It illustrates the historical moment when the United States shifted from a weak confederation to a stronger national framework. The artwork contains additional period-specific visual details beyond the AP syllabus but helps students visualize the founding process. Source.

Even with these limitations, the Articles represented an important early experiment in republican government. They showcased ongoing concerns about protecting liberty from potential tyranny, a central theme that continued into the debates surrounding the Constitution.

Pressures That Compelled Reform

By the mid-1780s, multiple problems revealed the need for stronger national institutions. Economic instability grew as states issued competing currencies, raised trade barriers against one another, and struggled to repay war debts. Congress remained unable to act decisively during foreign policy crises, and rebellions such as Shays’ Rebellion exposed weaknesses in national authority. Many American leaders concluded that a new constitutional framework was necessary to address these systemic problems.

These pressures led directly to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, where delegates sought to strengthen national power while still honoring the revolutionary commitment to limited government. The process required balancing change with continuity, ensuring that reforms did not undermine hard-won protections for individual rights and state sovereignty.

Continuities from the Articles to the Constitution

Although the Constitution introduced major structural reforms, it preserved several foundational principles rooted in the Articles:

Commitment to republicanism, defined as government based on popular sovereignty and representative institutions.

Concerns about centralized authority, which carried over into systems designed to limit federal power.

Recognition of states as key political units forming a union, maintaining their own reserved powers even under a stronger federal system.

Ongoing debates over liberty versus authority, shaping provisions such as limits on federal powers and, eventually, the Bill of Rights.

Republicanism: A political ideology emphasizing governance by elected representatives and the sovereignty of the people, rather than rule by monarch or hereditary elite.

These continuities reassured skeptics that stronger institutions would not erase the revolutionary emphasis on liberty and local self-government.

A significant continuity also appeared in foreign policy concerns. Under both systems, American leaders faced challenges from European powers seeking influence in North America, and states often disagreed on how to respond. The Constitution retained the idea that unified action was necessary, even as it expanded federal capacity to direct diplomacy and national defense.

Transformative Changes Under the Constitution

Despite important continuities, the Constitution represented a major shift toward stronger, more dynamic national institutions. The new government featured:

A bicameral legislature with enhanced authority to tax, regulate trade, and enforce laws.

A separate executive branch, headed by a president capable of implementing national policies and conducting diplomacy.

A federal judiciary with the power to interpret laws, resolve interstate disputes, and provide uniformity in legal interpretation.

These innovations responded directly to problems experienced under the Articles. For the first time, the national government could operate independently of the states, allowing it to raise revenue, maintain an army, and manage national affairs effectively.

These shifts reflected a broad consensus that the national government required greater authority, especially in matters of finance, diplomacy, and interstate commerce.

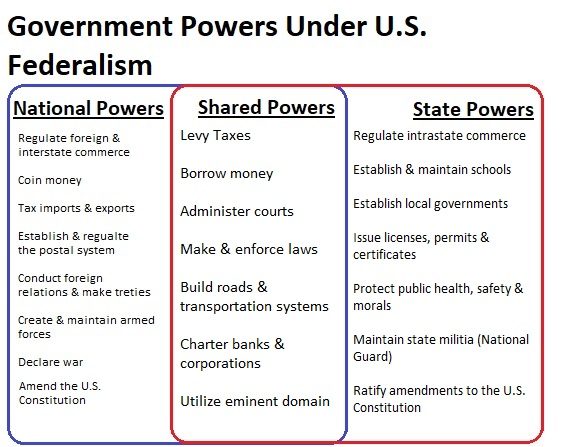

This Venn diagram illustrates how the Constitution divides governmental powers into federal, state, and shared categories. It reinforces the notes’ discussion of federalism as a balance of strengthened national authority and preserved state powers. The diagram includes specific examples of powers that extend slightly beyond the AP syllabus but support conceptual understanding. Source.

Federalism: A system of government in which power is divided between national and state governments, with each retaining distinct spheres of authority.

These shifts reflected a broad consensus that the national government required greater authority, especially in matters of finance, diplomacy, and interstate commerce. Yet even as the Constitution expanded federal power, it preserved crucial protections against tyranny.

Balancing Strengthened Governance with Liberty

A key reason the Constitution succeeded politically was its careful combination of stronger national institutions with mechanisms designed to prevent centralized abuse.

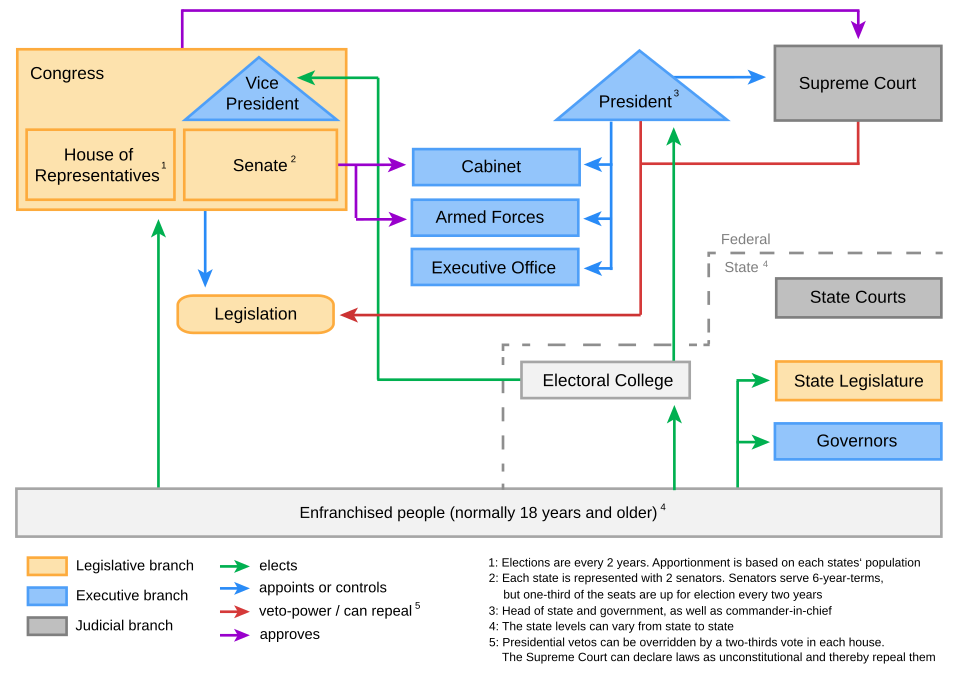

This diagram shows how the U.S. Constitution structures the legislative, executive, and judicial branches within a broader political system. It supports the discussion of separated powers and mechanisms designed to limit governmental overreach. The diagram includes additional political actors beyond the AP subsubtopic but helps contextualize how constitutional structures operate in practice. Source.

These features demonstrated that although the nation shifted to a more robust central government, the guiding principle of protecting liberty—so prominent under the Articles—remained central.

Enduring Concerns and the Legacy of the Transition

Even after ratification, debates persisted over how much power the federal government should wield. The emergence of Federalists and Democratic-Republicans in the 1790s reflected lingering tensions inherited from the Articles: disagreements over centralized authority, economic policy, and foreign affairs. In this sense, the transition from the Articles to the Constitution marked not an abrupt break, but an evolution in American political thought.

The shift to “stronger national institutions,” as emphasized in the AP specification, occurred alongside enduring fears about concentrated power. These dual concerns—strength and restraint—defined the political culture of the early republic and shaped the long-term trajectory of U.S. constitutional development.

FAQ

Many Americans associated strong central authority with the abuses they believed Parliament and the Crown had committed before the Revolution. A decentralised system felt safer and more consistent with local autonomy.

The states also viewed themselves as sovereign political units, making them reluctant to cede power to a national government that did not yet have a proven track record of safeguarding liberty.

The inability of the Confederation Congress to handle economic instability, interstate disputes and foreign threats convinced many delegates that reform was essential.

These experiences shaped the Convention’s consensus that national authority needed strengthening, even among delegates deeply wary of concentrated power. The challenge lay in designing mechanisms that balanced effectiveness with restraint.

Key concerns included fears of executive overreach, potential military tyranny and the protection of individual rights.

These anxieties encouraged delegates to adopt measures such as separated powers, regular elections and restrictions on federal authority. The later addition of the Bill of Rights further reflected enduring worries about protecting personal and political freedoms.

Under the Articles, states issued their own currencies, imposed tariffs on one another and developed incompatible commercial policies, creating economic fragmentation.

A stronger national government promised:

Uniform trade regulation

More reliable national revenue

Greater credibility in repaying war debts and negotiating international agreements

These measures were seen as essential for long-term economic development.

States continued to control areas such as property law, local taxation, education and most civil and criminal justice, preserving substantial autonomy.

They also influenced the federal government through mechanisms like Senate elections (prior to the 17th Amendment) and control over voting qualifications, demonstrating that state authority remained integral to the political system.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the United States Constitution represented continuity from the Articles of Confederation.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid area of continuity (e.g., continued emphasis on republicanism, fear of centralised authority, preservation of state powers).

1 mark for providing accurate contextual detail about how this continuity existed under the Articles of Confederation.

1 mark for explaining how this feature persisted under the Constitution.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which the ratification of the Constitution marked a significant change from the government created under the Articles of Confederation.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for establishing a clear argument or thesis about the degree of change.

1–2 marks for describing specific weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation relevant to national authority (e.g., lack of taxation power, inability to regulate interstate commerce, no executive).

1–2 marks for explaining corresponding constitutional changes that strengthened national institutions (e.g., creation of executive and judiciary, power to tax, power to enforce laws).

1 mark for recognising at least one area of continuity rooted in fears of centralised power or the preservation of state authority.