AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Constitution created a limited yet dynamic central government that embodied federalism, balancing authority between national and state governments.’Introduction

The framing of the U.S. Constitution established a limited yet dynamic central government capable of addressing national challenges while protecting liberty, balancing powers between federal authority and the states.

The Purpose of a Limited but Dynamic Central Government

The Constitution emerged from years of dissatisfaction with the Articles of Confederation, whose intentionally weak central government had produced economic instability, diplomatic weakness, and domestic unrest. In response, delegates at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 sought to design a government strong enough to govern effectively yet constrained enough to prevent tyranny. Their solution was a limited but dynamic federal structure—“limited” through enumerated powers, separated powers, and checks and balances, and “dynamic” through flexible governing mechanisms able to respond to new national needs.

Federalism: Dividing and Balancing Power

Federalism refers to the constitutional division of authority between national and state governments, creating a two-level system of governance designed to protect both local autonomy and national unity.

Federalism: A system of government in which power is constitutionally divided between a central (national) government and regional (state) governments.

The Constitution strengthened national authority compared to the Articles but preserved substantial state power. This balance was achieved through multiple design features:

Enumerated and Implied Powers

The national government received enumerated powers—specific authorities listed in the Constitution such as regulating interstate commerce, coining money, declaring war, and conducting diplomacy. At the same time, the Necessary and Proper Clause (also known as the Elastic Clause) created space for implied powers, allowing Congress to adapt its actions to unforeseen circumstances. These implied powers enabled the government to remain dynamic rather than rigidly fixed to eighteenth-century conditions.

State Powers and the Tenth Amendment

States retained broad authority over matters not delegated to the federal government. The Tenth Amendment later clarified this division by affirmining that powers not granted to the national government, nor denied to the states, were reserved to the states or the people. This preserved local political traditions and ensured that everyday governance continued to occur at the state level.

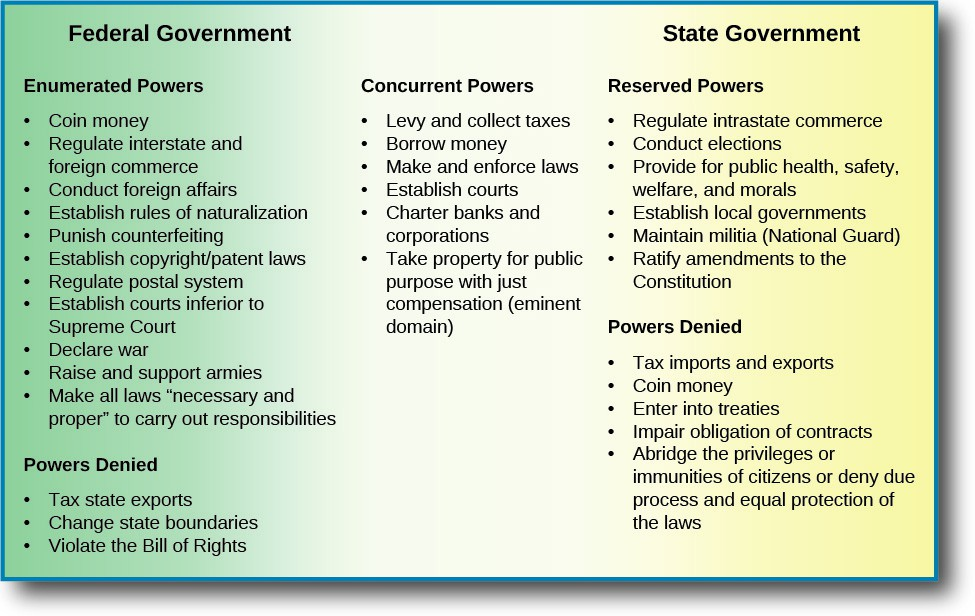

This chart compares the federal government’s enumerated powers, the states’ reserved powers, and concurrent powers, illustrating how authority is divided in the U.S. federal system. It also lists powers denied to each level of government, underscoring constitutional limits that prevent domination by either side. Some examples, such as postal services or eminent domain, provide detail beyond the syllabus but remain appropriate for AP-level understanding. Source.

Checks and Balances Within the Central Government

To maintain limited government, the Framers embedded a system of checks and balances, ensuring that no branch could dominate. This internal balancing reinforced the broader federal principle by preventing power concentration at the national level. The system worked in several key ways:

Legislative checks, such as Congress’s authority to approve budgets, declare war, and override vetoes.

Executive checks, including the president’s power to veto legislation and command the military.

Judicial checks, allowing federal courts to review laws and executive actions for constitutionality, a principle later solidified in Marbury v. Madison (1803).

These overlapping authorities forced cooperation and limited unilateral action.

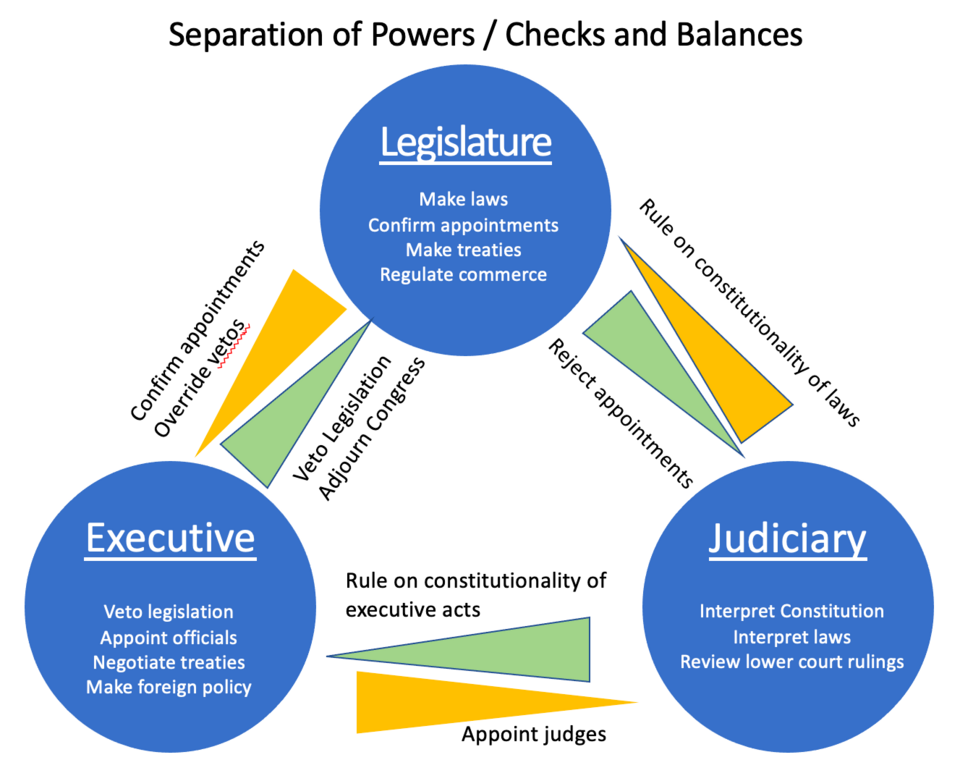

This diagram shows the three branches of the U.S. federal government and the checks and balances each exercises over the others. The arrows and labels demonstrate how separated powers still interact to prevent tyranny. The inclusion of specific checks, such as vetoes and judicial review, adds detail beyond the syllabus but aligns with AP-level expectations. Source.

A Dynamic Government Capable of National Action

Although constrained, the new central government was designed to be energetic, a term Alexander Hamilton used to describe the ability to govern decisively. Several mechanisms supported this dynamism.

Flexibility Through Broad Constitutional Language

The Constitution’s framers avoided excessive specificity, enabling future generations to interpret its provisions in light of changing circumstances. Clauses related to taxation, defense, commerce, and national welfare empowered the federal government to address emerging challenges such as economic regulation, infrastructure development, and internal security.

National Supremacy

The Supremacy Clause established that federal law takes precedence over state law when conflicts arise. This prevented states from undermining national initiatives and ensured that the central government could act cohesively on matters of national importance.

Supremacy Clause: The constitutional principle stating that federal law is the “supreme Law of the Land,” outranking conflicting state laws.

This principle helped stabilize the young republic by preventing state-level obstruction of federal policies.

Institutional Innovations Supporting Limited yet Dynamic Governance

The Constitution’s structural innovations supported its dual goals of limitation and adaptability.

Bicameral Legislature

Congress was divided into two chambers—the House of Representatives, reflecting population, and the Senate, providing equal state representation. This arrangement balanced the interests of large and small states and slowed legislative processes to encourage deliberation. It also allowed state governments, through their senators (originally chosen by state legislatures), to retain influence in national politics.

Independent Executive Branch

A single president, elected independently of Congress, ensured decisive leadership in foreign affairs, military matters, and national crises. Yet executive power was checked by requirements for Senate approval of treaties and appointments, demonstrating the continual interplay of limitation and dynamism.

Federal Judiciary

A national court system ensured uniform interpretation of federal law. Over time, the judiciary played a major role in delineating the boundary between federal and state authority, reinforcing federal supremacy while preserving states’ constitutional roles.

The Constitution as a Framework for Evolving Governance

The Constitution established not a static blueprint but a governing framework capable of evolution. The amendment process, while difficult, allowed for constitutional growth, and early political leaders used the document’s flexibility to shape policies such as Hamilton’s financial program and Washington’s diplomatic neutrality. These decisions illustrated how a limited government could nonetheless exercise robust authority when necessary.

The resulting system blended structural safeguards with adaptive capacity, ensuring that the federal government could meet national challenges without abandoning foundational commitments to liberty and checks on power.

FAQ

Colonial resistance to Parliamentary overreach, such as taxation without representation and the use of standing armies, shaped American fears of concentrated authority.

These experiences encouraged the Framers to incorporate structural limits like separated powers and federalism to prevent a recreated form of British-style central dominance.

The nation faced unpredictable economic, diplomatic, and territorial challenges after independence. Rigid structures like those under the Articles of Confederation had proved unworkable.

A dynamic framework allowed the new government to manage crises, administer national policy, and adjust to future circumstances without abandoning checks on authority.

Delegates disagreed sharply over the proper strength of the national government. Some, like Hamilton, argued for substantial central authority, while others insisted on protecting state sovereignty.

Compromises produced a federal system with enumerated powers for the national government and residual powers for the states, allowing varied regional interests to coexist.

Early administrations interpreted federal powers broadly to address national needs:

Washington asserted federal supremacy during the Whiskey Rebellion.

Hamilton’s financial programme relied on implied powers.

Adams used federal authority to address diplomatic tensions with France.

These actions shaped expectations for energetic national leadership.

States continued to control most aspects of daily governance, including property law, civil and criminal courts, and local economic regulation.

Before the 17th Amendment, state legislatures selected senators, giving states direct influence in national legislation.

Federalism also ensured that any powers not delegated to the national government remained in state hands, preserving regional authority.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the U.S. Constitution created a limited central government.

Mark scheme

1 mark for identifying a valid limiting feature (e.g., separation of powers, checks and balances, enumerated powers, federalism).

1 mark for describing how this feature restricts federal authority (e.g., prevents concentration of power, requires cooperation between branches).

1 mark for providing a clear, accurate explanation linked to the constitutional framework (e.g., the executive can veto legislation, limiting Congress’s power).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the U.S. Constitution created a central government that was both limited and dynamic. Use specific historical evidence to support your answer.

Mark scheme

1 mark for identifying at least one method of limiting federal power (e.g., reserved state powers, checks and balances, enumerated powers).

1 mark for explaining how this method restricts national authority.

1 mark for identifying at least one method that made the government dynamic (e.g., Necessary and Proper Clause, broad constitutional language, national supremacy).

1 mark for explaining why this method allowed federal flexibility or adaptation.

1 mark for accurate use of specific historical or constitutional evidence (e.g., Constitutional Convention debates, early national policies demonstrating flexibility).

1 mark for a clear analytical connection showing how both limitation and dynamism worked together in the constitutional system.