AP Syllabus focus:

‘In the South, antislavery efforts were largely limited to unsuccessful rebellions by enslaved people against bondage.’

Southern resistance to slavery during 1800–1848 reflected the determination of enslaved people to challenge bondage despite overwhelming repression, limited resources, and hostile legal systems.

Southern Context and Constraints on Antislavery Action

Enslaved people in the South lived within a system designed to suppress organized resistance. Slave codes, enforced by local governments and private patrols, strictly limited movement, communication, and gatherings among enslaved people.

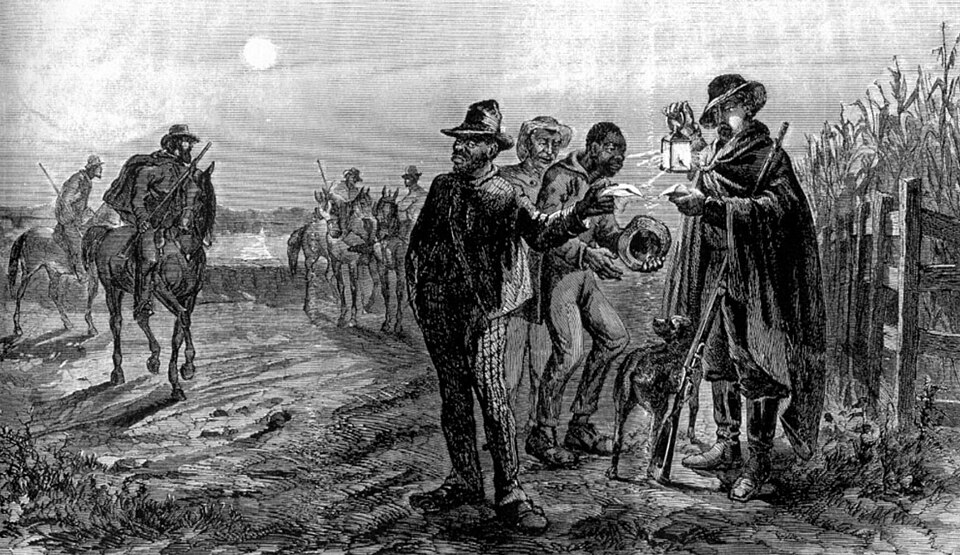

This illustration portrays a slave patrol in Mississippi, an armed mounted force tasked with monitoring enslaved people, checking passes, and hunting runaways. It provides concrete visual context for the enforcement mechanisms that supported slave codes. The scene includes some extra period detail beyond the syllabus but reinforces the climate of surveillance that restricted antislavery action. Source.

Slave codes: Laws in slaveholding states that restricted enslaved people’s mobility, education, assembly, and legal protections to prevent rebellion and enforce racial hierarchy.

The demographic realities of many Southern regions intensified planter fears and resulted in even stricter enforcement. In areas with significant enslaved populations, White Southerners viewed any expression of discontent as a direct threat to the social order. As a result, antislavery actions—especially those involving collective defiance—were met with rapid and severe retaliation.

Forms of Enslaved Resistance

Everyday Resistance

Although most enslaved resistance did not take the form of large-scale rebellion, enslaved people developed strategies to undermine slavery from within. These actions were small but constant, demonstrating both dissatisfaction and a desire for autonomy.

Examples included:

Work slowdowns to reduce productivity

Feigned illness to avoid labor demands

Breaking or misusing tools as quiet sabotage

Maintaining family and religious practices to assert cultural independence

Covert literacy to build communication networks and self-empowerment despite legal risk

These forms of resistance served as expressions of agency but did not fundamentally threaten the institution of slavery on a systemic level. They nevertheless reminded enslavers that control was never absolute.

Organized and Violent Resistance

While everyday resistance was widespread, collective rebellions were far rarer due to surveillance and the threat of lethal punishment. Still, several major attempts occurred and had lasting consequences for Southern society.

Key attempted or actual uprisings included:

Gabriel’s Rebellion (1800): A planned uprising in Virginia that was uncovered before execution; it resulted in executions and heightened restrictions.

Denmark Vesey’s Conspiracy (1822): An alleged plot in Charleston involving free and enslaved African Americans; the plan was suppressed, and the city imposed tighter controls on Black life.

Nat Turner’s Rebellion (1831): The most significant rebellion of the period, in which Turner and his followers killed dozens of White Southerners before suppression.

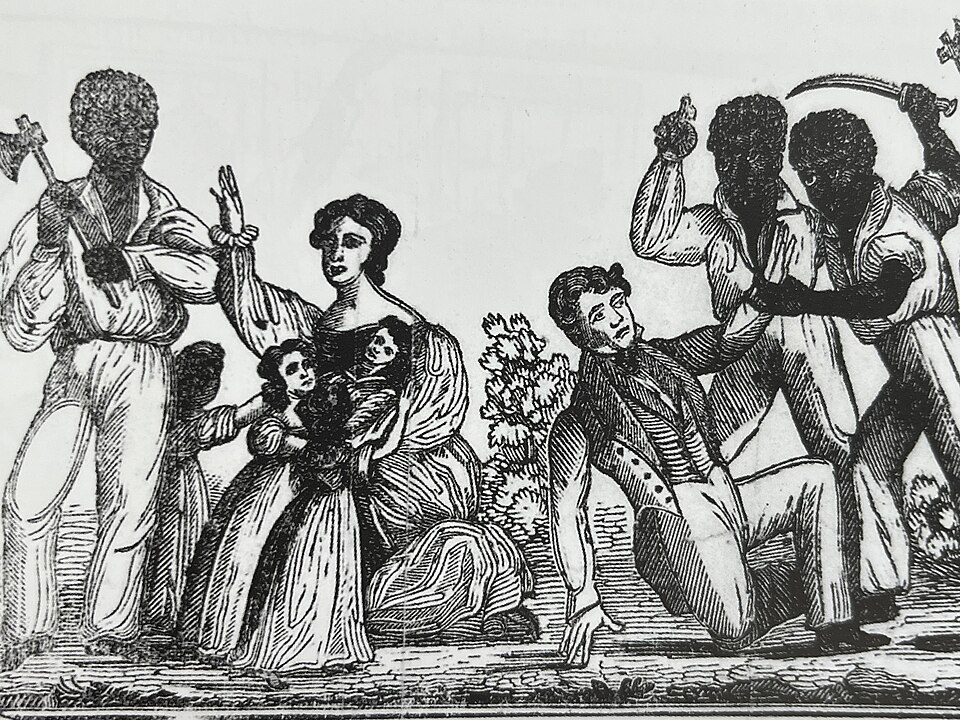

This engraving depicts scenes from Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831, illustrating the scale and violence of the uprising. It helps explain why the revolt so deeply alarmed white Southerners and led to harsher slave codes and patrols. The dramatic details exceed syllabus requirements but reinforce the fear-driven repression that followed. Source.

Rebellion: An organized, often violent, collective effort to overthrow an existing authority or oppressive system.

Even though rebellions were uncommon and typically unsuccessful, they generated widespread fear among White Southerners. This fear shaped Southern political culture and helped close the region further to criticism of slavery.

Why Southern Antislavery Action Was Limited

Structural Barriers

Southern society had embedded slavery into its economic, political, and legal foundations. Cotton production, strengthened by the global market and innovations like the cotton gin, enriched plantation owners and solidified slavery as essential to regional prosperity. Because wealth and political power were concentrated among enslavers, the system was defended through:

State laws banning abolitionist literature

Restrictions on manumission

Suppression of Black religious meetings

Prohibitions against teaching enslaved people to read

Lack of Institutional Support

Unlike the North, the South lacked abolitionist societies, free Black communities with political influence, or religious institutions openly critical of slavery. Southern churches increasingly defended slavery as a positive good, limiting moral avenues for antislavery expression.

Surveillance and Violence

Slave patrols, militias, and community surveillance networks made sustained organization nearly impossible. These forces responded swiftly to rumors of resistance, often punishing not only suspected rebels but also uninvolved enslaved people to deter future attempts.

Aftermath of Rebellions and Heightened Repression

Expansion of Legal Restrictions

Major rebellions, especially Nat Turner’s, triggered waves of repressive legislation. States reduced the rights of free African Americans, tightened patrol systems, and expanded censorship. Enslaved people’s ability to travel, assemble, worship, or communicate was increasingly restricted.

Political Closure

Southern leaders framed resistance as justification for intensifying slavery’s grip. State legislatures blocked both internal and external antislavery petitions. Public discussion of gradual emancipation—a topic once debated—was effectively silenced after 1831.

Social Impact on Enslaved Communities

Despite repression, rebellion attempts inspired continued hope and strengthened communal bonds. Oral traditions, spirituals, and clandestine networks preserved the memory of resistance and sustained a sense of identity and resilience. However, the heavy reprisals made subsequent large-scale uprisings even more difficult.

The Syllabus Emphasis on Limits

From 1800 to 1848, antislavery action in the South remained constrained by systemic violence, legal restrictions, and the entrenched political power of enslavers. Enslaved people continued resisting in countless everyday forms, but large-scale rebellions were rare, swiftly suppressed, and unable to fundamentally challenge slavery in the region during this period.

FAQ

Enslaved people relied on discreet, informal networks such as religious meetings, work gangs, and family gatherings to exchange information. Whisper networks allowed ideas to spread without written communication.

They also used coded language, songs, and symbolic messages to avoid detection. These strategies enabled communication while minimising the risk of punishment.

Free Black communities were small but influential cultural and economic centres for enslaved people, offering models of autonomy that challenged slavery’s legitimacy.

However, strict laws limited their ability to organise, travel, or publicly support resistance. Their presence nonetheless provided indirect encouragement by demonstrating the possibility of self-determination.

Southern newspapers often exaggerated or sensationalised rumours of rebellion, portraying enslaved people as inherently dangerous.

This contributed to a climate of fear that justified harsher slave codes and increased patrol activity.

Bulletins also reinforced racial hierarchies by framing rebellion as an attack on social order rather than a response to oppression.

Several factors contributed to early detection of planned uprisings:

Informants who provided information to authorities under coercion

The difficulty of coordinating large groups under constant surveillance

Strict pass systems limiting movement

These conditions made secrecy difficult to maintain, leading to early arrests and harsh reprisals.

Enslaved people often used Christian teachings to articulate moral critiques of slavery, drawing on themes of liberation and justice.

Spirituals and religious gatherings fostered emotional unity and hope, which strengthened resistance culture.

However, many white-controlled churches promoted obedience, prompting enslaved worshippers to form secret or semi-private religious spaces where more radical interpretations could flourish.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why large-scale antislavery action in the American South between 1800 and 1848 was limited.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., strict slave codes).

1 additional mark for explaining how this reason limited antislavery action (e.g., prevented enslaved people from gathering or communicating).

1 further mark for providing a specific historical example or detail (e.g., surveillance by slave patrols).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which violent resistance, such as Nat Turner’s Rebellion, influenced Southern political and social responses to antislavery efforts between 1800 and 1848.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that violent resistance heightened fears among White Southerners.

1 mark for explaining a political response (e.g., the tightening of legal restrictions or censorship).

1 mark for explaining a social response (e.g., increased patrol activity or repression).

1 mark for discussing how these responses limited antislavery action more broadly.

1 mark for using a specific example such as Nat Turner’s Rebellion or Denmark Vesey’s alleged plot.

1 mark for a reasoned judgement about the extent of influence (e.g., arguing that violent uprisings had significant but not universal impact on Southern policy).