AP Syllabus focus:

‘Over time, reformers debated strategy and inclusion—for example, whether women’s rights goals should focus mainly on White women.’

Reform movements in the early nineteenth century were dynamic yet fractured, shaped by disagreements about aims, strategies, and who counted as a legitimate participant in expanding social change.

Major Sources of Division in Reform Movements

Reform activity in the early nineteenth century expanded dramatically, but cooperation among reformers was never guaranteed. Conflicts emerged over ideology, tactics, and inclusiveness, particularly as diverse groups attempted to enact moral, social, and political improvements.

Democratic Impulses and the Problem of Inclusion

Many movements reflected the era’s growing emphasis on democratic participation, yet they also confronted the question of who possessed the moral authority to direct reform. While activists championed the improvement of society, many disagreed about whether these efforts should extend to all Americans or privilege certain groups.

Democratic participation: The belief that broad involvement in public life strengthens society and legitimizes political or social change.

Reform, therefore, was not simply about addressing societal problems; it was also about negotiating the boundaries of belonging within the expanding republic.

Women’s Rights and Divisions Over Inclusion

One of the most visible arenas of disagreement involved the intertwined movements for women’s rights and other reform causes, particularly abolitionism. Women played indispensable roles in voluntary associations, petition campaigns, and public advocacy. However, the growing prominence of female activists generated conflict.

Debates Over Women’s Public Role

Some reformers argued that women could legitimately organize and speak publicly on moral questions, especially within abolitionist networks. Others believed such activity violated prevailing separate spheres ideology, which held that women belonged primarily in the domestic realm.

Separate spheres ideology: The belief that men properly occupied public and political spaces while women were best suited to domestic and moral influence within the household.

This disagreement produced significant tension within national abolitionist societies, contributing to schisms between more conservative and more egalitarian wings of the movement.

Limits of Inclusion: Focus on White Women

Even within the emerging women’s rights movement, divisions emerged over whose rights were being defended. Many early activists framed their goals around expanding opportunities for White middle-class women, often overlooking or sidelining the experiences of African American women, working-class women, and Indigenous women. This selective inclusion reflected deeper tensions about race, citizenship, and social status.

Bullet points highlighting major debates:

Whether women should hold leadership positions within broader reform organizations

Whether public speaking by women was acceptable or improper

Whether the movement should prioritize rights for all women or mainly for White women

How women’s rights claims interacted with abolitionist and temperance goals

Whether women should engage in petitioning, lecturing, and convention leadership

Divisions in Abolitionism

Abolitionism was one of the most ideologically vibrant reform movements, yet it was also deeply divided. Reformers frequently disagreed about whether rapid, uncompromising action or gradual change offered the most effective path to ending slavery.

Immediatists vs. Gradualists

The rise of immediatism, especially under figures like William Lloyd Garrison, demanded the immediate abolition of slavery without compensation. Opponents countered that gradual emancipation was more politically achievable and less socially disruptive. These divisions shaped organizational strategies, messaging, and alliances with other reform movements.

Racial Equality as a Point of Conflict

Even among reformers committed to ending slavery, disagreements existed over whether abolition should also include full racial equality. Many White abolitionists—especially in more conservative organizations—opposed equal social or political rights for African Americans. As a result, Black activists frequently formed their own conventions, churches, literary societies, and mutual-aid networks. Black women reformers, however, faced the double burden of racism and sexism within movements that claimed to speak for universal rights.

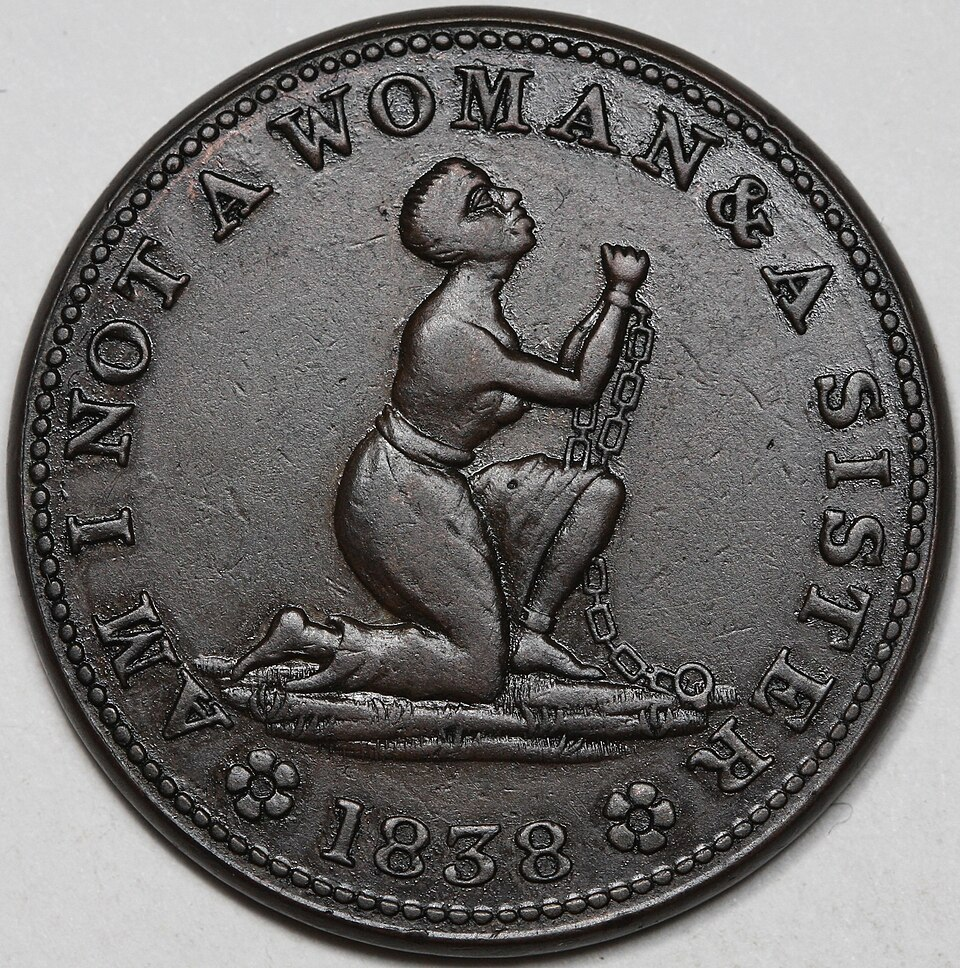

This nineteenth-century antislavery token shows a kneeling enslaved woman with the inscription “Am I Not a Woman & a Sister,” demanding recognition of both gender and racial equality. Reformers used this motto in petitions, meetings, and print culture to argue that liberty and womanhood could not be separated. Although the token includes numismatic details beyond the syllabus, it reflects ideas that shaped debates within U.S. reform movements. Source.

Bullet points on abolitionist fractures:

Disagreement over immediate vs. gradual emancipation

Conflicts regarding women’s participation and leadership

Tensions over interracial cooperation

Debates about moral suasion vs. political action

Disputes over whether abolition entailed full citizenship rights

Strategic Debates Across Reform Movements

Beyond questions of inclusion, reformers also disagreed intensely about how best to achieve social change.

Moral Suasion vs. Political Engagement

Some activists believed that moral suasion—appealing to individual conscience—was the only legitimate strategy for reform. They argued that political involvement compromised moral integrity. Others contended that legislative action, party politics, and petition campaigns were essential tools for securing widespread change.

Moral suasion: A reform strategy that sought to persuade individuals to change their behavior through ethical and religious appeals rather than through laws or coercion.

These disagreements shaped the direction and effectiveness of numerous causes, from temperance to prison reform.

Utopian Experiments vs. Practical Reform

Certain groups advocated creating utopian communities—self-contained social experiments designed to model moral perfection. Critics argued that such communities withdrew from mainstream society and offered little practical influence on national reform. This debate highlighted tensions between idealistic goals and pragmatic approaches.

Fragmentation and Long-Term Impacts

The divisions that shaped reform movements during this era weakened cooperation but also broadened the reform landscape. Activists who felt excluded frequently built their own organizations and articulated alternative visions for American society. As a result, debates over strategy and inclusion intensified reform energy even as they fractured reform coalitions.

Opponents mocked female lecturers as unfeminine and dangerous to social order, using satire and cartoons to discourage women from speaking publicly or leading reform societies.

This political cartoon caricatures reformer Frances Wright with the head of a goose as she lectures publicly, reflecting anxieties about women speaking on moral and political issues. Critics used such imagery to portray outspoken women as unfeminine and socially disruptive. The cartoon illustrates the cultural pressures shaping debate within reform movements over women’s activism. Source.

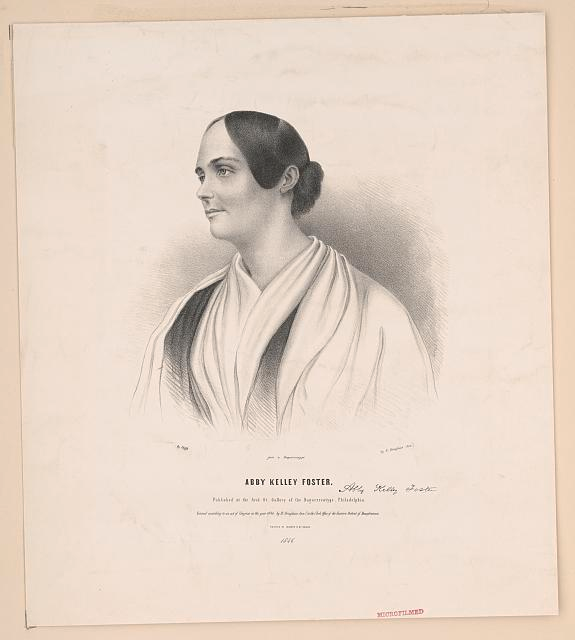

Activists such as Abby Kelley and the Grimké sisters insisted that women’s full participation in abolition was a moral duty, even when that stance contributed to organizational splits.

This lithograph of Abby Kelley Foster depicts one of the era’s most influential abolitionist and women’s rights activists, whose leadership forced antislavery societies to confront questions of gender equality. Her prominence helped catalyze major organizational divides over whether women should hold public roles in reform. Although the portrait’s production slightly postdates early debates, it reflects the leadership that shaped antebellum reform conflicts. Source.

FAQ

Religious motivations often united reformers, but differing theological interpretations produced disagreements over acceptable tactics and goals.

Some evangelicals believed reform must focus on individual moral regeneration, opposing political activism as too worldly. Others argued that structural change through legislation was essential to moral progress.

These tensions surfaced in abolitionism, temperance, and women’s rights, creating ideological boundaries even among reformers with shared religious convictions.

Many activists worried that combining controversial causes would alienate moderate supporters.

Some believed abolitionism was already politically fragile, and tying it to wider demands for women’s equality risked backlash from the public, churches, and legislators.

Others argued that reform movements needed clear, single-issue focus to achieve results, leading to strategic disagreements over coalition-building.

Reformers in New England generally embraced more radical strategies, including public speaking by women and interracial organising.

In contrast, many Midwestern and Mid-Atlantic reformers preferred gradualist or less confrontational methods, arguing that local political cultures would not support radical action.

These regional variations often influenced voting blocs within national organisations, shaping leadership contests and policy direction.

African American women frequently organised independent societies, mutual-aid networks, and church-based activism that highlighted racism within predominantly white movements.

Their participation drew attention to exclusionary practices, such as segregated seating at meetings or unequal speaking opportunities.

By insisting that racial and gender justice were inseparable, Black women reformers pushed reform movements to confront issues many white activists preferred to avoid.

Petition campaigns were central to abolitionist and women’s rights organising, but they raised questions about women’s participation in political life.

Critics argued that petitioning Congress violated notions of feminine propriety, while supporters saw it as an accessible tool for democratic engagement.

Debates intensified when women began creating mass petition networks, forcing reform organisations to decide whether these activities were legitimate political expression or unacceptable public behaviour.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why debates emerged within antebellum reform movements over the appropriate public role of women.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., prevailing gender norms such as the separate spheres ideology).

• 1 mark for explaining how this reason generated disagreement (e.g., some reformers believed women speaking publicly was improper).

• 1 mark for providing a historically accurate example or further explanation (e.g., disputes within abolitionist societies over whether women could serve as leaders or lecturers).

Maximum: 3 marks.

(4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1800–1848, analyse how disagreements over inclusion and strategy contributed to divisions within major reform movements such as abolitionism and women’s rights.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1–2 marks for identifying relevant disagreements (e.g., disputes over interracial cooperation, the role of women, immediate versus gradual emancipation).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how these disagreements caused fragmentation (e.g., the split within the American Anti-Slavery Society).

• 1–2 marks for using specific evidence or examples to support analysis (e.g., the activism of Abby Kelley Foster, tensions between abolitionists over women’s leadership, competing strategies such as moral suasion versus political action).

Responses that attempt analysis but lack developed explanation or specific evidence should be awarded at the lower end of the mark range.

Maximum: 6 marks.