AP Syllabus focus:

‘African Americans participated in political efforts and community institutions that aimed to change their legal and social status.’

Free African Americans in the early republic organized politically, built community institutions, and advanced a determined activism that sought to challenge discriminatory laws and reshape their precarious legal status.

Free Black Activism in the Early Republic

In the decades after the American Revolution, free African Americans—a population that grew gradually through manumission, self-purchase, and Northern emancipation laws—worked strategically to improve their legal and social position. Although the United States upheld profound racial inequality, free Black communities developed persistent organizational and political efforts intended to secure protection, opportunity, and recognition within the republic. These efforts unfolded in both Northern and Upper Southern urban centers, where dense Black populations made collective action more possible.

Building Community Institutions as Bases for Activism

Free African Americans recognized that achieving legal and social change required strong internal networks. As a result, they created institutions that supported mutual aid, education, economic development, and political coordination.

Black churches, especially African Methodist Episcopal (AME) congregations, served as hubs for activism, providing organizational space and leadership structures.

Mutual aid societies, such as the Free African Society of Philadelphia, offered financial assistance, burial funds, and community governance.

Schools and literary societies provided education that free African Americans viewed as essential for citizenship, public respect, and long-term advocacy.

Mutual Aid Society: A voluntary organization providing financial and social support to community members, often serving as a foundation for broader political action.

These institutions allowed community leaders to communicate political goals, train new activists, and present unified demands to local governments. They also became protective structures that helped free Black Americans withstand discriminatory laws and racial hostility.

A key outcome of this institutional life was the rise of prominent free Black leaders—such as Richard Allen, James Forten, and Prince Hall—who advocated for abolition, civil rights, and fair treatment under the law while modeling leadership within their own communities.

Portrait of Rev. Richard Allen, an influential free Black religious leader, abolitionist, and founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. His ministry and organizing in Philadelphia helped turn Black churches into centers of community life and political activism for free African Americans. This image focuses on Allen himself and does not depict the broader institutions around him, which are discussed in the text. Source.

Political Efforts to Change Legal Status

Free African Americans sought formal political change even though they were often barred from voting or holding office. Their activism centered on petitions, conventions, public protest, and participation in broader reform movements.

Petition Campaigns and Challenges to Discriminatory Laws

Petitioning was a crucial strategy because it allowed those without electoral rights to engage directly with political authorities. Free Black activists frequently petitioned state legislatures, Congress, and local governments to:

Oppose the kidnapping and sale of free Blacks into slavery

Demand protection from mob violence and racial harassment

Challenge laws that restricted movement, employment, and testimony in court

Resist disenfranchisement efforts in states where free Black men had previously voted

Petition drives both articulated African Americans’ grievances and asserted their presence within the political culture of the early republic.

Petition: A formal written request submitted to a government authority, used by disenfranchised groups to seek policy changes.

The persistence of these petitions helped keep racial injustice visible, even when legislatures failed to act in response.

Black Conventions and Collective Political Voice

Beginning in the 1830s, free African Americans organized national and state “colored conventions” that brought together delegates from different regions to coordinate political objectives.

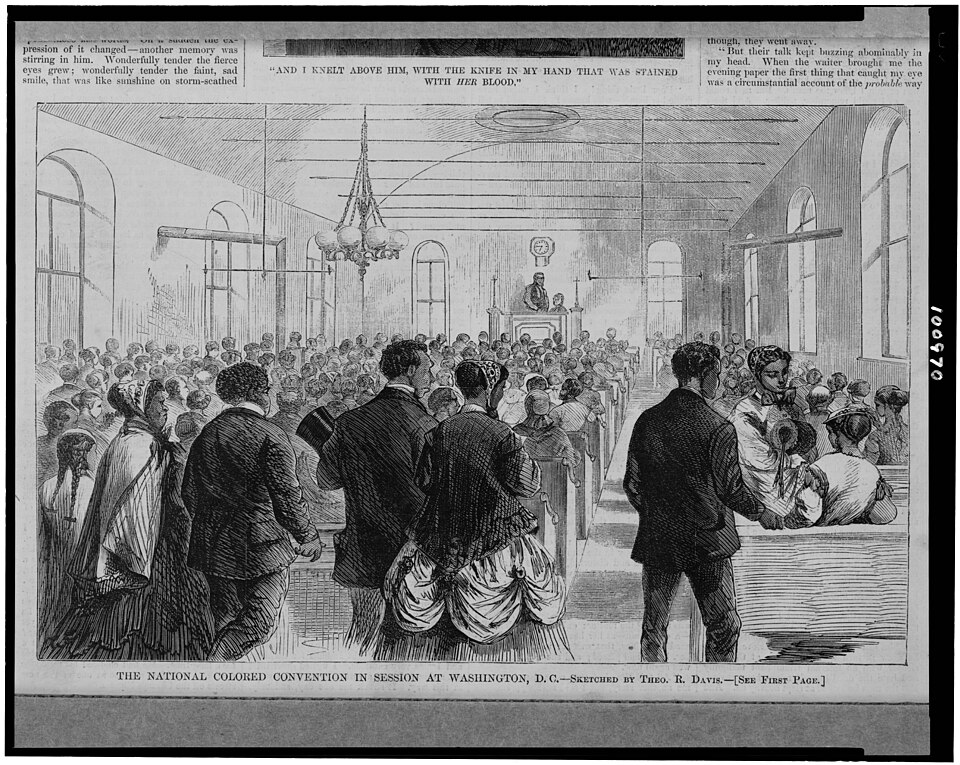

Wood engraving of a National Colored Convention meeting in Washington, D.C., showing Black delegates seated beneath a raised platform and speaker’s podium. The scene illustrates the scale and formality of collective Black political organizing in the nineteenth century. The specific convention depicted dates from 1869, slightly later than the early-republic focus, but reflects the same Colored Conventions tradition discussed in the text. Source.

These conventions addressed issues such as:

Legal discrimination and unequal citizenship

Education access and economic opportunity

Strategies to resist colonization proposals

Strengthening Black institutions nationwide

The conventions created a shared political language and a unified, national approach to contesting racial subordination.

Resistance to Colonization Efforts

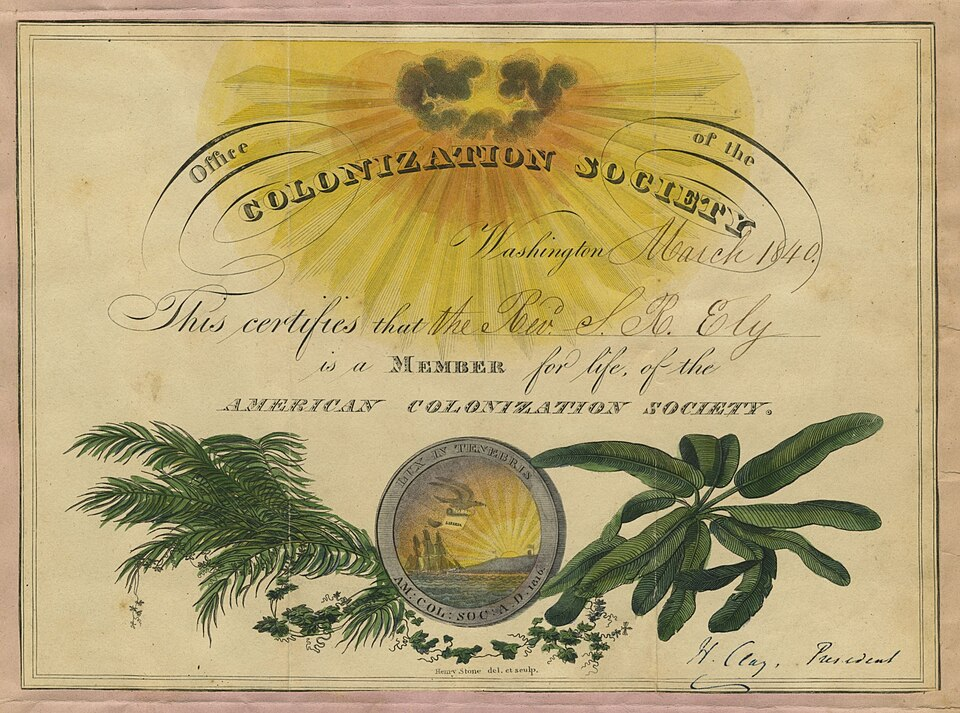

A significant political challenge arose from the American Colonization Society (ACS), which promoted the removal of free African Americans to Liberia.

Membership certificate for the American Colonization Society, issued to Rev. Samuel Rose Ely and signed by Henry Clay. The ornate design highlights that colonization was backed by prominent White political leaders and formal institutions, offering context for why free Black communities organized vigorously against it. The certificate includes decorative elements and specific names not required by the syllabus but serves to illustrate the kind of organization that activists opposed. Source.

Most free Black communities opposed colonization, viewing it as an attempt to strengthen slavery by eliminating free Black populations who provided evidence of African American autonomy.

Activists argued that they were entitled to full citizenship in the United States and made this case through resolutions, public protests, and newspaper editorials. Their opposition helped delegitimize colonization among Northern reformers and strengthened anticolonization sentiment.

Engagement with the Antislavery Movement

Free African Americans played essential roles in shaping the abolitionist movement, participating as writers, lecturers, organizers, and contributors to antislavery newspapers. Their lived experiences provided moral authority and credibility to antislavery campaigns. Collaborations with sympathetic White activists expanded the reach of Black political demands and integrated them into national debates about slavery and citizenship.

At the same time, African American activists insisted on addressing Northern racism as part of the abolitionist agenda. Their dual focus—ending slavery and expanding civil rights—ensured that the struggle for freedom was framed as both a national institution to be dismantled and a system of local discrimination to be challenged.

Community Institutions as Foundations for Status Change

Free African Americans’ schools, churches, newspapers, and mutual aid networks not only strengthened community life but also provided platforms for political mobilization. These institutions enabled African Americans to document abuses, educate future leaders, coordinate regional efforts, and articulate demands for legal protections. Through these channels, free Black Americans transformed limited resources into effective political tools.

Overall, free African American activism in the early republic demonstrated agency, resilience, and strategic organization. Their efforts did not overturn systemic racism, but they forged durable community institutions and advanced a political tradition that continued shaping civil rights struggles for generations.

FAQ

Free Black activists often relied on community-based communication networks that allowed political ideas to circulate outside formal institutions.

They used sermons, church meetings and reading circles to share arguments about rights and justice. Ministers frequently embedded political messages in religious teachings, offering both moral framing and practical guidance.

Black-run newspapers such as Freedom’s Journal also served as an important platform. Although literacy levels varied, newspapers were read aloud in community gatherings, enabling wide engagement with political debates.

Black women contributed significantly through church work, mutual aid societies and informal political organising, even though they rarely appeared in official records.

They raised funds for schools, supported fugitives from slavery and organised community relief programmes. Women also hosted meetings in their homes, creating safe spaces for planning and discussion.

Through literacy promotion, Sunday schools and charitable associations, Black women strengthened community stability and enhanced the social foundations necessary for political activism.

Education was viewed as essential for demonstrating intellectual capability and countering racist arguments used to justify discrimination.

Access to schooling:

Improved employment prospects

Increased literacy, enabling participation in petitions and political writing

Provided leadership training for future activists

Education also symbolised citizenship readiness. Free African Americans believed that a well-educated community could challenge stereotypes and claim a legitimate place within American civic life.

Responses varied by region, but free African Americans used a combination of adaptation and resistance strategies.

Some relocated to states with fewer restrictions or moved to urban centres where Black institutions could offer support. Others relied on networks of church leaders, lawyers and abolitionist allies to contest discriminatory laws.

In some cases, activists documented abuses and presented them to state officials or antislavery societies, hoping public exposure would pressure governments to amend unjust regulations.

Free Black activists faced legal, social and economic barriers that restricted the impact of their efforts.

Key limitations included:

Widespread disenfranchisement, which denied political leverage

Risk of mob violence when advocating publicly

Limited financial resources for sustaining institutions and campaigns

Persistent White resistance to racial equality, even in the North

Despite these obstacles, activists built durable organisational structures that supported later civil rights movements.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one specific way in which free African Americans in the early republic sought to improve their legal or social status, and briefly explain why this method was significant.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a specific method (e.g., petitioning legislatures, forming mutual aid societies, founding independent Black churches, participating in coloured conventions).

1 mark for briefly explaining how this method supported efforts to challenge discriminatory laws or assert rights.

1 mark for linking the method to a broader aim, such as protecting free Black communities from injustice or shaping public policy.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how free African Americans used community institutions and political activism to challenge racial discrimination and attempt to change their status between 1800 and 1848.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks for describing community institutions such as Black churches, schools, or mutual aid societies.

1–2 marks for explaining how these institutions enabled political organisation, leadership development, or collective identity.

1–2 marks for discussing specific political strategies, such as petitioning, conventions, or opposition to the American Colonisation Society, and showing how these were intended to improve legal or social status.