AP Syllabus focus:

‘Although most White Southerners owned no enslaved people, many Southern leaders argued that slavery was central to the Southern way of life.’

Southern society in the early republic developed a powerful hierarchical structure in which slavery shaped politics, culture, and economic identity, reinforcing elite power and defining regional life.

Southern Social Hierarchy and Power Structures

Southern society in the early nineteenth century rested on a pronounced hierarchical order that reinforced the authority of wealthy planters. Although most White Southerners owned no enslaved people, political and cultural power remained concentrated among the planter elite. These elites dominated state legislatures, controlled local courts, and influenced policy debates at both the state and federal levels. Their influence made slavery not simply an economic system but also an anchor of social and political identity.

The Planter Elite

The planter class, consisting of families who owned twenty or more enslaved laborers, sat atop Southern society. Their control of land, enslaved labor, and credit networks gave them disproportionate political authority. They often served in elected office or exercised influence through personal connections and patronage. While numerically small, their economic resources allowed them to shape regional norms and defend slavery as essential to order and prosperity.

Yeoman Farmers and Non–Slaveholding Whites

Most White Southerners were yeoman farmers, cultivating small plots of land without enslaved labor. Despite lacking direct economic investment in slavery, many supported the institution because it upheld a racial hierarchy that elevated their social status above African Americans. Some aspired to become slaveholders, reinforcing the idea that slavery symbolized social mobility and economic success. Political leaders capitalized on this aspiration, promoting proslavery ideology as a protector of White liberty and independence.

Poor Whites and Social Dependence

At the bottom of the White social structure were poor Whites, landless laborers who faced economic insecurity. Even they often defended slavery because it ensured that the most dangerous and demeaning work fell to enslaved people. This reinforced a social order in which all Whites—regardless of class—belonged to the dominant racial group. The system promised them social superiority despite their limited material prospects.

Economic Foundations of Proslavery Power

Slavery underpinned the South’s agricultural economy, making the institution central to economic identity and political power.

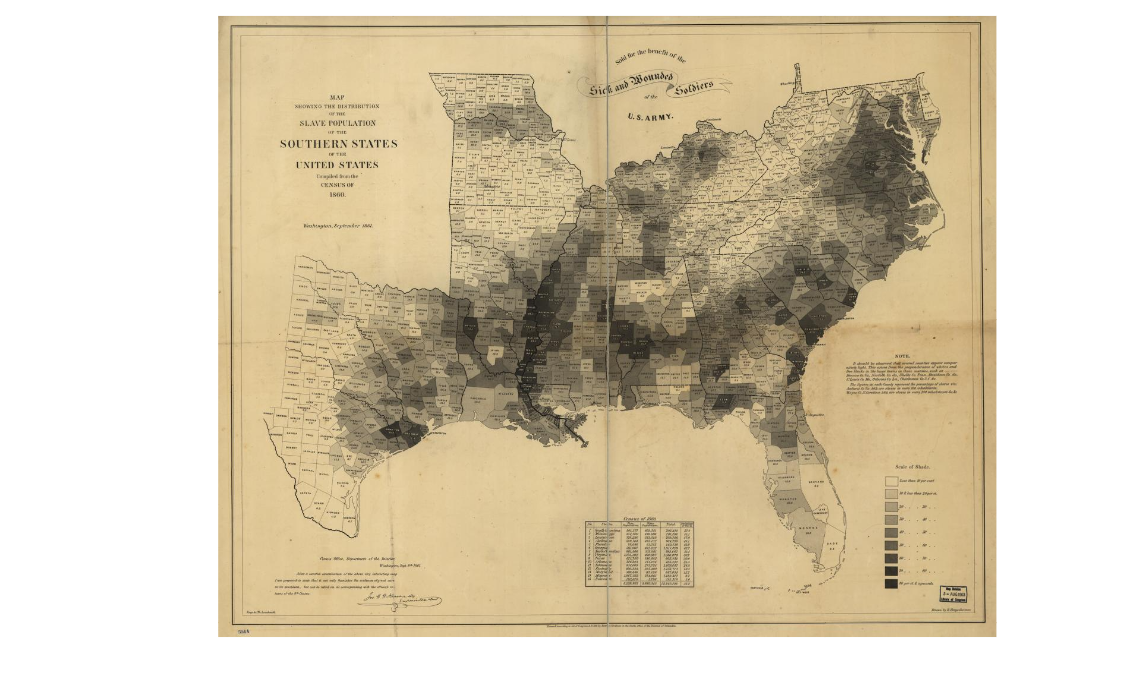

This 1861 map, based on the 1860 census, shows the percentage of enslaved people in each county across the Southern states. Darker shading indicates areas where enslaved people made up a very high share of the population, illustrating how slavery was concentrated and economically vital. The map includes county-level statistics and shading scales beyond the AP syllabus, but these details help demonstrate how slavery and Southern society were geographically intertwined. Source.

The cultivation of staple crops, particularly cotton in the Deep South, relied heavily on enslaved labor. Access to enslaved labor determined agricultural productivity, land values, and access to credit, ensuring that slavery remained deeply intertwined with wealth and influence.

Cotton, Capital, and Political Influence

The expansion of cotton production accelerated after the invention of the cotton gin and the opening of fertile lands in the Southwest. Planters reinvested profits into purchasing additional enslaved laborers, strengthening a cycle in which slavery generated wealth that reinforced political leadership. The symbiotic relationship between slavery and capital accumulation helped cement planter authority across the region.

Regional Cooperation and Shared Interests

Even non-slaveholding regions aligned politically with planters because the Southern economy depended on plantation output, trade networks, and the presence of enslaved labor. Merchants, lawyers, and small farmers all benefited indirectly from plantation wealth. This created a broad coalition committed to preserving slavery as an economic foundation.

Proslavery Ideology and Intellectual Defense

Southern leaders crafted a sophisticated proslavery argument designed to counter growing Northern criticism and defend slavery as essential to the Southern way of life. These arguments blended economic claims, racial theories, religious interpretations, and social paternalism.

Racial Ideology and Claims of Natural Hierarchy

Proslavery thinkers argued that African Americans were inherently inferior and suited for labor-intensive agricultural work. They claimed that enslavement protected societal order by maintaining a racial hierarchy that preserved stability and minimized class conflict among Whites. These ideas justified legal restrictions on African Americans and reinforced White unity across class lines.

Racial Hierarchy: A structured belief system asserting that racial groups can be ranked by innate abilities, used in the South to justify slavery.

These arguments permeated public discourse, shaping political speeches, newspapers, and social norms.

Religious and Paternalistic Justifications

Many Southern ministers defended slavery as consistent with Christian teachings, citing biblical passages to claim divine sanction. Planters also advanced a paternalistic argument, asserting that enslaved people received protection, guidance, and care from their enslavers. According to this logic, slavery supposedly offered stability, religious instruction, and material support that African Americans would not achieve on their own.

Slavery as a “Positive Good”

By the 1830s, proslavery leaders such as John C. Calhoun asserted that slavery was not a necessary evil but a “positive good.” They argued that slavery allowed White citizens to enjoy political freedom by freeing them from manual labor, while enslaved people were allegedly cared for throughout life.

This mid-19th-century daguerreotype shows Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, a leading defender of slavery in national politics. Calhoun’s arguments framed slavery as a “positive good” and tied it to states’ rights and Southern honor. The image contains no additional textual information beyond the syllabus but helps students associate proslavery ideology with a specific historical figure. Source.

This ideological shift marked a more aggressive regional stance, especially amid rising abolitionist activity in the North.

Political Defense of the Southern Way of Life

Efforts to defend slavery shaped Southern politics at every level. State constitutions protected slaveholders’ property rights, and Southern representatives in Congress fought to maintain the balance of power against antislavery forces. Political unity in defense of slavery transcended class divisions, promoting the belief that the institution was central to Southern identity, security, and prosperity.

FAQ

Southern newspapers played a major role in normalising and spreading proslavery ideology. Editors frequently published articles portraying slavery as economically indispensable and morally justified, ensuring these themes reached a wide readership.

They also criticised abolitionist materials, framing them as threats to Southern stability.

Through selective reporting and political commentary, newspapers helped sustain regional unity around slavery.

Many Southern churches reinforced proslavery beliefs by interpreting scripture in ways that supported the institution. Clergy often preached sermons emphasising obedience, paternalism, and social order.

• Biblical references were used to claim divine sanction for slavery.

• Churches discouraged anti-slavery discussion, presenting dissent as both socially and spiritually dangerous.

This religious reinforcement helped embed proslavery ideology in community life.

Prominent planter families often intermarried, forming dense kinship networks that concentrated wealth and political authority. These ties allowed them to coordinate political strategies and maintain control over local institutions.

• Relatives supported each other’s bids for office.

• Family alliances controlled regional economic resources, amplifying their influence.

Such networks helped ensure that proslavery voices remained dominant in Southern politics.

Many feared that ending slavery would disrupt the rigid racial hierarchy that guaranteed their privileged status. Without slavery, they believed free Black people would compete with them for employment and social standing.

Additionally, proslavery politicians warned that emancipation could lead to violence or social disorder, influencing poorer Whites to see slavery as essential to their own security.

Southern schools often incorporated proslavery themes into textbooks, lessons, and civic instruction. Educational materials portrayed slavery as historically normal, socially beneficial, and crucial to Southern prosperity.

• Textbooks depicted enslaved people as content or dependent.

• Lessons emphasised states’ rights and regional loyalty.

By shaping young people’s perspectives, Southern education helped reproduce proslavery worldviews across generations.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why many non-slaveholding White Southerners supported the continuation of slavery in the early nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for identifying a valid reason, such as the belief that slavery upheld a racial hierarchy.

• 1 additional mark for explaining how this belief reinforced the social status of poorer Whites.

• 1 further mark for clearly linking support for slavery to aspirations for upward mobility or protection from the most difficult labour.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse how Southern political leaders justified slavery as essential to the Southern way of life in the period 1800–1848. In your answer, consider both economic and ideological arguments.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• Up to 2 marks for describing economic arguments, such as reliance on staple-crop agriculture and the wealth and political power of the planter elite.

• Up to 2 marks for describing ideological arguments, including racial theories, paternalism, or the idea of slavery as a “positive good.”

• Up to 2 marks for analysis that connects these justifications to broader Southern identity, political unity, or resistance to Northern criticism.