AP Syllabus focus:

‘Southern business leaders relied on producing and exporting traditional agricultural staples, strengthening a distinctive Southern regional identity.’

Staple-Crop Agriculture and the Formation of a Southern Identity

The antebellum South’s reliance on staple-crop agriculture shaped economy, society, and culture, reinforcing a distinctive regional identity rooted in land, labor systems, and export markets.

The Centrality of Staple Crops in the Southern Economy

Staple-crop agriculture—centered on cotton, tobacco, sugar, and rice—formed the economic backbone of the early nineteenth-century South. The most transformative of these was cotton, which rose dramatically in profitability due to technological and market changes.

Staple crop: A primary agricultural product grown in large quantities for sale and export rather than local consumption.

Cotton became the dominant staple because of soaring European demand, especially from British textile industries, and the expanding land base available for plantation cultivation. The success of cotton was so significant that the crop became known as “King Cotton,” reflecting its profound influence on economic production and regional politics. As plantations expanded westward into fertile lands such as Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, staple-crop agriculture deepened its hold over Southern society.

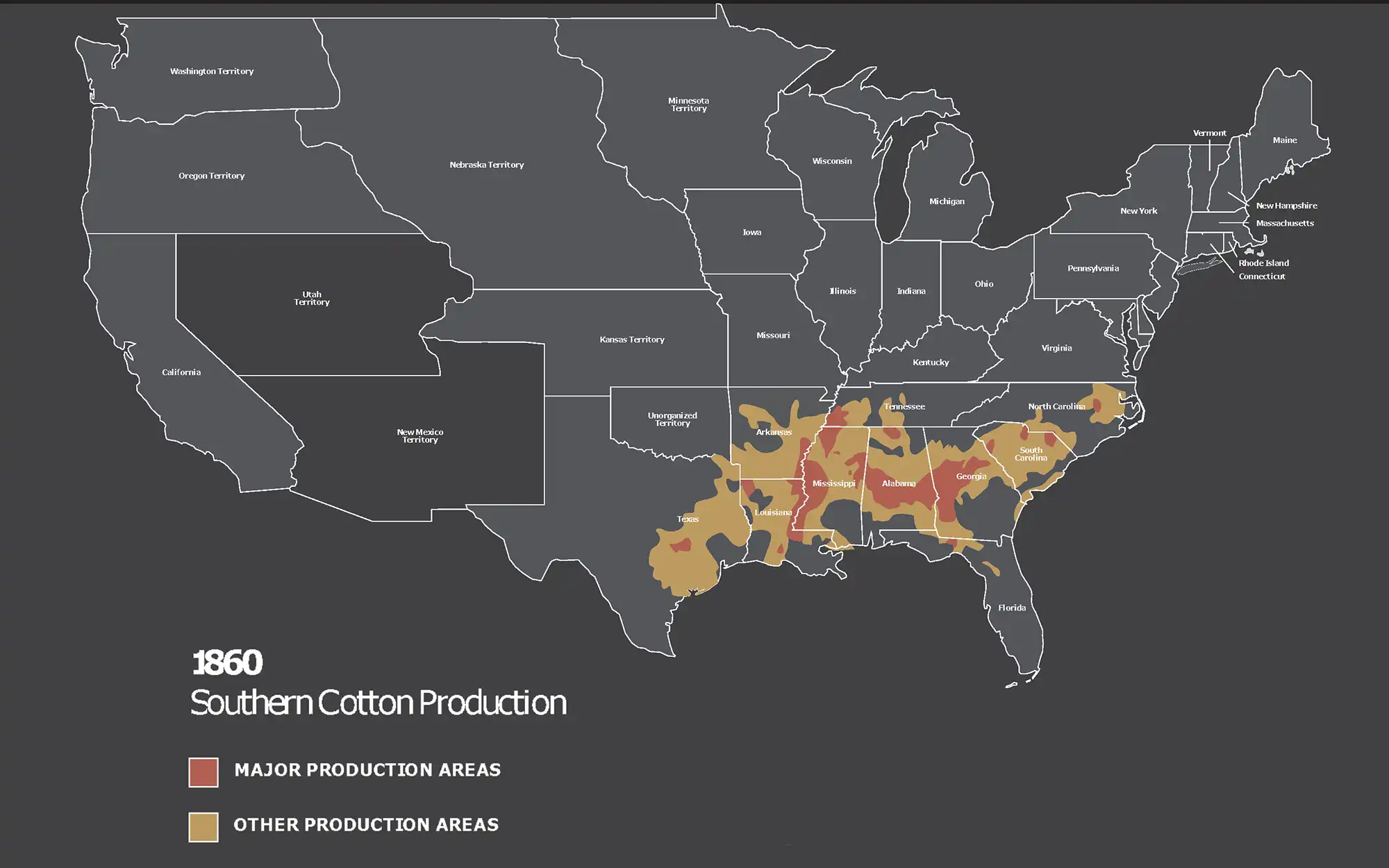

This map of Southern cotton production in 1860 illustrates how cotton cultivation was concentrated in a broad belt stretching from South Carolina to eastern Texas. The dense shading reflects the profitability of staple-crop agriculture and its alignment with plantation expansion into new territories. The map includes additional detail about “major” and “other” production areas, which extends beyond the syllabus by indicating relative intensity of cotton output. Source.

Plantation Systems and Labor Structures

Organized Production and Labor Demands

Staple crops—especially cotton and sugar—required large, organized labor forces and long growing seasons. Southern business leaders relied on the plantation system, a large-scale agricultural model centered on enslaved labor, hierarchical management, and export-oriented production.

Plantation system: A large-scale agricultural operation dependent on coerced labor and focused on producing high-volume export crops.

Although not all white Southerners owned enslaved people, the plantation model shaped regional ideology and economic patterns. Even small farmers aspired to the wealth and social status associated with large landholding and enslaved labor.

Key Characteristics of the Plantation Economy

Economies of scale enabled plantations to control large, contiguous tracts of land.

Enslaved labor supplied year-round labor for planting, harvesting, processing, and maintenance.

Export markets, especially Britain and northern U.S. textile manufacturers, ensured steady demand.

Agricultural specialization, rather than diversification, tied wealth to global commodity prices.

These characteristics linked Southern prosperity to a labor-intensive agricultural model and discouraged major investment in industrial development.

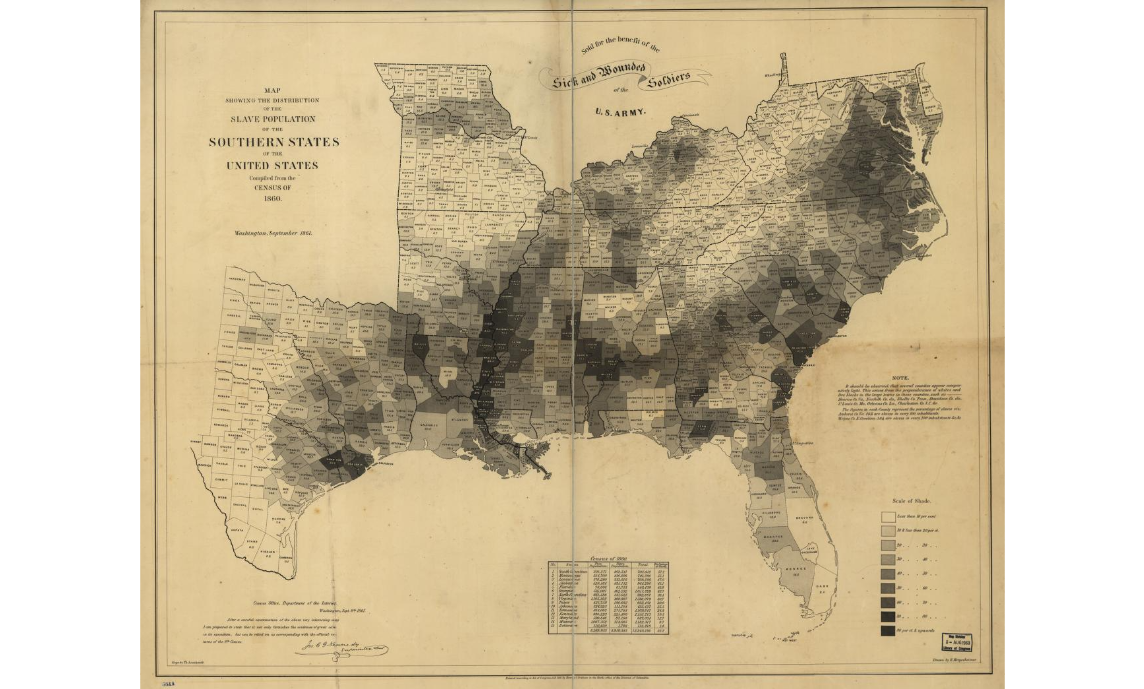

This 1860 map depicts the distribution of the enslaved population across the Southern states, with darker shading marking counties where enslaved people made up a higher share of residents. The heaviest concentrations align with major cotton- and sugar-producing regions, demonstrating how staple-crop agriculture depended on coerced labor. The map includes precise demographic figures by county, offering additional detail beyond the syllabus requirement. Source.

Southern Business Leadership and Regional Identity

Southern business and political leaders consistently portrayed staple-crop agriculture as essential to both prosperity and the region’s cultural integrity. Their arguments strengthened a Southern identity distinctly different from the North’s industrializing path.

How Staple Crops Shaped Regional Identity

Economic worldview: Leaders celebrated cotton and tobacco as the foundation of Southern wealth and the region’s place in global trade.

Social hierarchy: Plantation owners emerged as a powerful elite whose influence shaped political culture and economic policy.

Cultural ideals: The region embraced values tied to rural life, landownership, paternalism, and agrarian independence.

Southern leaders contrasted this agrarian world with what they saw as the overly commercial, industrial, and urban North, heightening cultural differences.

Export Markets and Southern Commercial Networks

Integration into National and International Trade

Staple-crop agriculture required extensive commercial networks. The South developed close economic ties with:

Northern banks and shipping firms that financed and transported crops.

European markets, particularly British and French textile industries, that consumed much of the cotton crop.

Gulf and Atlantic port cities, including New Orleans, Charleston, Mobile, and Savannah.

These connections fostered regional pride in the South’s role as a crucial supplier to global industry. They also encouraged Southerners to defend policies that protected export-oriented agriculture.

Economic Effects on the Region

Fluctuations in global prices could strongly influence regional prosperity.

Profitability of exports reinforced commitment to land expansion and new territories.

The South remained dependent on importing manufactured goods, limiting internal industrial growth.

Despite these vulnerabilities, Southern leaders celebrated staple-crop agriculture as the most natural and prosperous economic foundation for their region.

Agricultural Specialization and Lack of Diversification

The focus on staple crops discouraged diversification in both agriculture and industry. Many Southern communities invested almost exclusively in cotton or tobacco, neglecting subsistence crops and manufacturing.

Consequences of Specialization

Limited urbanization, as fewer manufacturing centers emerged.

Slow transportation development compared to the North, though some areas invested in river systems and ports.

Dependence on enslaved labor, embedded deeply into the region’s social and economic structures.

These trends reinforced an identity rooted in rural life and plantation dominance, differentiating the South from other American regions experiencing rapid industrial transformation.

Cultural Expressions of an Agrarian Region

Staple-crop agriculture informed Southern culture beyond economics. Regional literature, speeches, and political rhetoric emphasized themes of:

Agrarian virtue, depicting rural life as morally superior.

Family lineage and landholding, presenting plantations as markers of social prestige.

Resistance to external interference, particularly from federal or northern critics of slavery.

These cultural expressions strengthened the belief that the South’s staple-crop economy was central to its identity and must be preserved.

The Enduring Legacy

By centering economic life on staple-crop agriculture and defending it culturally and politically, Southern leaders forged a regional identity distinct from the broader United States. This identity—rooted in exports, plantations, and agricultural specialization—defined the region’s worldview and contributed significantly to long-term sectional tensions.

FAQ

Cotton’s high market value encouraged Southerners to maximise land for staple-crop cultivation rather than diversify their agriculture.

Planters often removed forests, depleted soils through intensive monoculture, and continually sought fresh land to maintain productivity.

This pattern made long-term soil health a lower priority than short-term profit, reinforcing continuous westward expansion.

Rivers such as the Mississippi, Alabama, and Savannah were essential transport routes for moving cotton and other staples to port cities.

Their navigability reduced shipping costs and made plantation locations along major waterways particularly advantageous.

This infrastructure shaped where plantations developed, strengthening the economic geography associated with Southern identity.

Many hoped to enter the plantation-owning class and saw agriculture as the region’s most prestigious economic path.

They also believed that the wealth generated by staple crops elevated the entire region’s status, even if they personally benefited little.

Cultural values tied to landownership further linked ordinary white Southerners to the plantation model.

Port cities like New Orleans, Mobile, and Charleston acted as commercial hubs where interior planters shipped their crops.

This created economic interdependence:

• Interior plantations supplied goods.

• Ports handled export logistics and financial services.

• Merchants and exporters relied on predictable crop cycles.

As a result, the fortunes of port cities rose and fell with staple-crop production.

Cotton grew well across large areas of the Deep South and required less specialised labour than rice or sugar.

The invention of the cotton gin and rising international demand made cotton economically superior to older staple crops.

Its adaptability, profitability, and link to global textile industries accelerated its dominance, reinforcing the region’s shared agricultural identity.

Practice Questions

Explain one way in which staple-crop agriculture shaped the economy of the antebellum South. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

• Identifies a valid economic effect of staple-crop agriculture (e.g., reliance on cotton exports, the profitability of tobacco or sugar).

2 marks:

• Provides a brief explanation of how staple-crop agriculture shaped the economy (e.g., created dependence on export markets, encouraged expansion of plantations).

3 marks:

• Offers a clear and accurate explanation linking staple-crop production to a broader economic pattern (e.g., how cotton linked the South to international trade networks, inhibited industrial development, or entrenched the plantation system).

Analyse the extent to which staple-crop agriculture contributed to the formation of a distinct Southern regional identity between 1800 and 1860. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

• Provides a general explanation of how staple-crop agriculture influenced Southern identity.

• Identifies at least one factor such as the plantation system, social hierarchy, or export-oriented economy.

• Shows basic understanding of historical context.

5 marks:

• Gives a developed analysis with specific examples (e.g., cotton’s role in “King Cotton” ideology, the social status of planters, the agrarian worldview).

• Demonstrates clear links between staple-crop agriculture and distinctive regional cultural, economic, or political features.

6 marks:

• Presents a well-structured argument evaluating the extent of agriculture’s influence on Southern identity.

• Integrates precise historical evidence (e.g., westward plantation expansion, entrenched enslaved labour, reliance on British textile demand).

• Explains both the primary influence of agriculture and, where relevant, acknowledges other contributing factors such as political defence of slavery or resistance to Northern industrial models.