AP Syllabus focus:

‘Overcultivation depleted land in the Southeast, pushing plantations westward to more fertile areas and enabling slavery to expand.’

Soil depletion across the Southeast accelerated plantation migration into the Southwest, where fertile lands supported expanding cotton production and deepened the entrenched, increasingly profitable institution of slavery.

Soil Exhaustion and Agricultural Depletion in the Southeast

By the early nineteenth century, intensive plantation agriculture strained the natural limits of Southeastern soils. Continuous monoculture, especially of tobacco and later cotton, steadily drained essential nutrients from the land. Planters often prioritized short-term profit over long-term sustainability, repeatedly planting the same crops without sufficient fallow periods. This practice reflected broader market pressures tied to global demand for agricultural staples and a desire for rapid commercial growth.

Monoculture: The agricultural practice of planting a single crop over a large area for multiple seasons, reducing soil fertility over time.

The resulting soil exhaustion diminished yields, raised production costs, and reduced profitability for plantation owners. Many began to view relocation as the most viable means of maintaining the scale and competitiveness of their enterprises. These environmental pressures thus acted as key drivers in motivating large numbers of planters to consider migration.

Despite recognizing the ecological damage caused by their methods, few planters adopted meaningful soil conservation strategies. Instead, exhausted land was often abandoned or sold at low prices, contributing to rural decline in parts of the Upper South. As Southeastern productivity waned, attention shifted westward, where newly accessible territories promised both fertile soil and expanding economic opportunity.

Westward Plantation Migration and the Movement into the Southwest

Plantation migration into the Southwest—including Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and eastern Texas—represented one of the most significant demographic and economic shifts of Period 4. Multiple factors interacted to encourage this movement, including land availability, federal Indian removal policies, and technological advancements.

Key Factors Driving Westward Expansion

Fresh, fertile soil in the Southwest offered dramatically improved yields compared to depleted Southeastern fields.

Federal land policies, including sales of public land at affordable rates, enabled planters to acquire large tracts suitable for plantation agriculture.

American Indian removal, especially after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, forcibly opened millions of acres to White settlement and plantation development.

Improved transportation, particularly river routes and emerging internal improvements, facilitated the movement of both goods and enslaved laborers.

As planters and their families relocated, they carried with them enslaved people, farming tools, livestock, and cultural practices rooted in the older plantation regions. The migration transformed the geography of the slave South, shifting its population center and economic dynamism toward the western frontier.

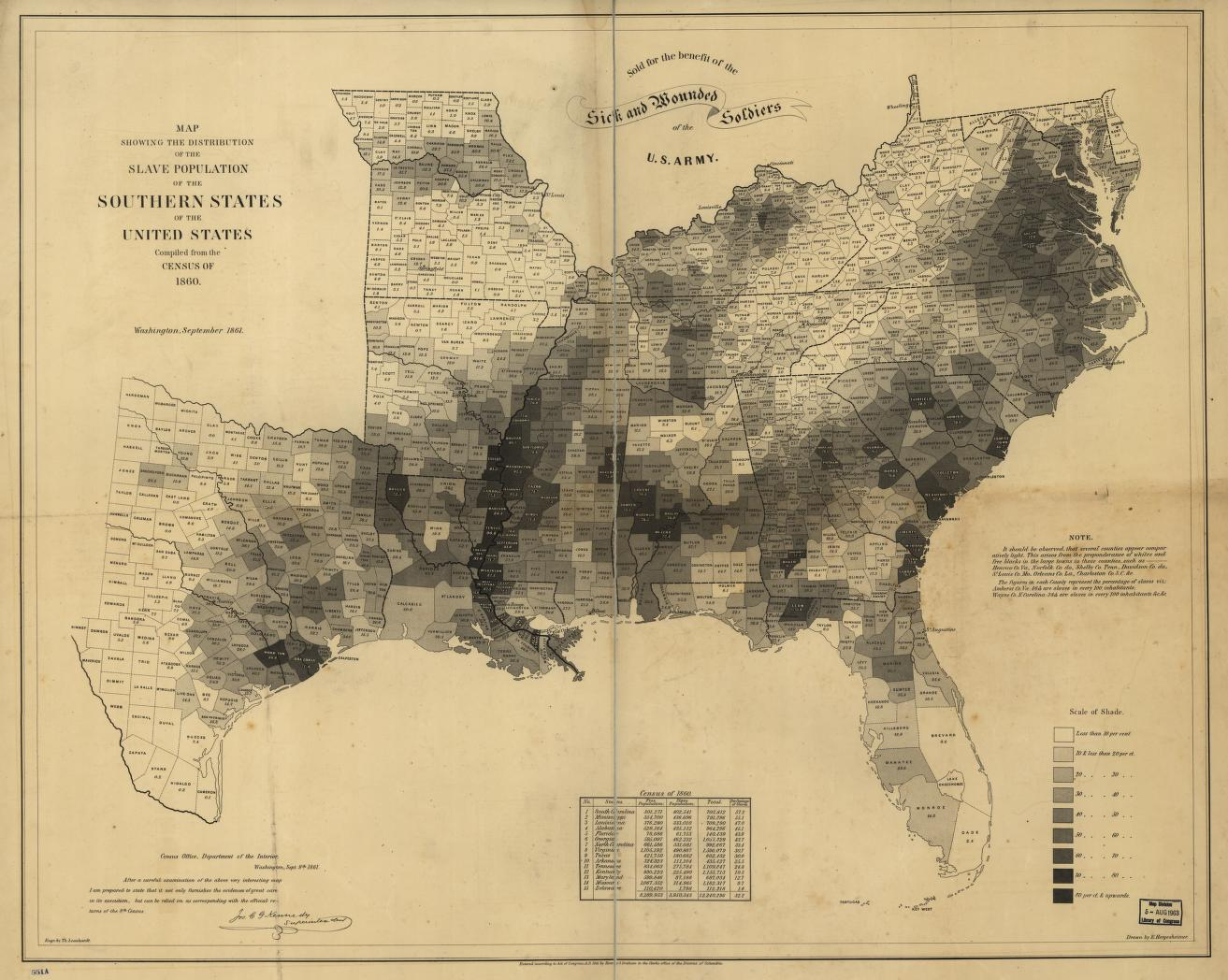

This map shades each southern county by the percentage of enslaved residents, illustrating how slavery deepened across the Deep South and Mississippi Valley as cotton plantations moved west. Although based on 1860 census data, it captures the regional pattern created by soil exhaustion, planter migration, and slavery’s expansion during 1800–1848. The darkest shaded regions reflect the highest concentrations of enslaved labor in the emerging Cotton Kingdom. Source.

Southwest: In this historical context, the region encompassing Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and eastern Texas, characterized by fertile soils ideal for cotton cultivation.

Unlike the more diversified agriculture of some Southeastern districts, these Southwest plantation zones focused overwhelmingly on cotton. This created a powerful economic engine that reinforced both settlement patterns and political priorities across the region.

Slavery’s Expansion and the Cotton Frontier

The migration of planters into the Southwest directly fueled the growth of slavery, transforming both the institution and the enslaved population’s geographic distribution. The expansion of cotton cultivation increased demand for enslaved labor, driving a massive internal movement of enslaved African Americans from the Upper South to the Deep South.

Mechanisms Facilitating Slavery’s Growth

The domestic slave trade intensified as planters purchased enslaved people to work newly established plantations.

Forced migration, often via overland coffles or river transport, uprooted enslaved families and communities.

Rising cotton prices strengthened planter incentives to expand plantation acreage and labor forces.

Legal and political structures protected slavery’s profitability and promoted territorial expansion aligned with slaveholding interests.

The resulting shift created what historians call the “Cotton Kingdom,” an expansive region stretching from South Carolina to Texas, unified by climate, crops, and the pervasive use of enslaved labor.

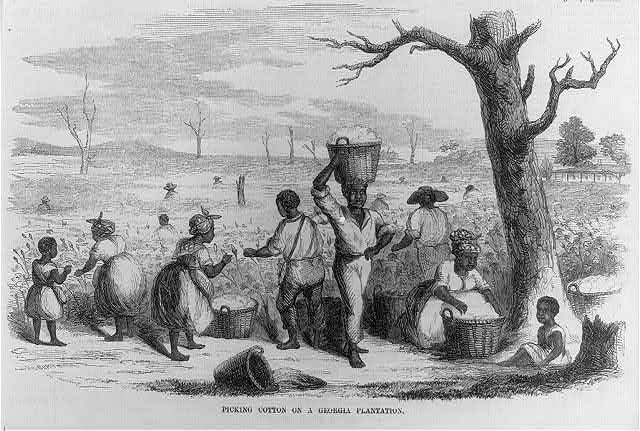

This engraving depicts enslaved laborers harvesting cotton on a Georgia plantation, demonstrating the intensive manual labor that made cotton expansion so profitable. It reflects the plantation system that exhausted soils in the Southeast and encouraged migration to more fertile western lands. Created in 1858, it shows the mature form of a system rooted in developments from 1800–1848. Source.

The forced relocation of enslaved people reshaped African American culture and community structures. Enslaved individuals attempted to preserve familial ties, cultural practices, and survival strategies, even as the disruptive effects of westward movement fractured established networks. The expansion of slavery also intensified national political tensions, as debates over its presence in new territories underscored increasingly sectional divisions.

Environmental, Economic, and Social Consequences

The combined processes of soil exhaustion, plantation migration, and slavery’s expansion reshaped the South in several enduring ways.

Major Results

Environmental degradation persisted in both the old and new plantation regions as cotton continued to deplete soils.

Regional economic divergence increased, with the Deep South becoming the dominant center of cotton production.

Entrenched dependence on enslaved labor grew, limiting economic diversification and reinforcing rigid social hierarchies.

Sectional tensions over slavery’s expansion escalated, setting the stage for later conflicts.

These interconnected developments defined the structural transformation of the South from 1800 to 1848, linking environmental change to economic ambition and human exploitation.

FAQ

Soil exhaustion harmed both groups, but small farmers faced sharper consequences. With fewer financial resources, they struggled to relocate or buy new land, leaving many trapped on depleted farms with declining yields.

Large plantation owners, by contrast, could sell off worn-out lands and reinvest profits into vast tracts in the Southwest. This helped concentrate wealth and widened economic inequality within Southern society.

The Southwest offered richer alluvial soils, particularly in the Black Belt region, which retained nutrients better than the heavily cultivated soils of Virginia and the Carolinas.

Its longer growing season, warmer temperatures, and reliable rainfall also made cotton cultivation more productive. These environmental advantages reduced labour costs and increased yields, making the region extremely attractive to migrating planters.

The growing demand for enslaved labour in the Southwest encouraged the rise of professional slave traders who created predictable transport routes and commercial networks.

• Traders moved enslaved people in coffles by land or via river systems, especially the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.

• Auctions in cities like New Orleans and Natchez became major hubs, linking Upper South sellers with Deep South buyers.

• This system made forced migration more efficient and profitable for those involved.

As planters relocated west, new slaveholding states increased the South’s representation in Congress, especially in the House of Representatives.

These states supported policies that promoted land expansion, protected slavery, and strengthened agricultural interests. Over time, this shifted political influence away from the older plantation states toward places like Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana, reinforcing sectional divisions.

Forced migration often broke apart families, with individuals sold separately as part of the domestic slave trade. Enslaved people developed strategies to preserve kinship and identity despite these ruptures.

• They created extended family networks with others who had undergone migration.

• Naming traditions and oral histories helped maintain cultural ties.

• Communal labour and shared hardship forged new bonds that replaced family members lost through forced relocation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which soil exhaustion in the Southeast contributed to the westward migration of plantation agriculture during the early nineteenth century.

Mark scheme

1 mark: Identifies a basic consequence of soil exhaustion (e.g., declining yields or reduced profitability).

2 marks: Explains how this consequence encouraged planters to seek new lands in the Southwest.

3 marks: Provides a clear, historically accurate explanation linking soil depletion, economic pressures, and the attraction of fertile western lands.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the westward expansion of plantation agriculture contributed to the growth of slavery between 1800 and 1848.

Mark scheme

1–2 marks: Provides a general description of plantation expansion or slavery’s growth, with limited detail.

3–4 marks: Explains at least one specific mechanism, such as the domestic slave trade, forced migration, or the profitability of cotton, and connects it to the expansion of slavery.

5–6 marks: Offers a well-developed analysis with multiple accurate factors (e.g., demand for labour, cotton market pressures, political protection of slavery) and explicitly links westward agricultural migration to the strengthening of slavery in the Deep South.