AP Syllabus focus:

‘Entrepreneurs helped create a market revolution in which market relationships expanded and the manufacture of goods became more organized.’

The Entrepreneurial Catalyst in the Market Revolution

Entrepreneurs were pivotal in driving the market revolution, a period marked by rapid economic transformation, increased commercial activity, and the shift from localised production to integrated regional and national markets. Their willingness to invest capital, adopt new ideas, and reorganise production processes helped accelerate the move away from traditional household manufacturing. This shift contributed to broader structural changes in the early American economy, linking labour, technology, and expanding markets in increasingly systematic ways.

Defining Entrepreneurs in the Early Nineteenth Century

Early American entrepreneurs differed from traditional artisans or local traders because they actively sought new methods to expand production and reach wider markets. They pursued opportunities created by population growth, rising demand, and improving transportation networks.

Entrepreneur: An individual who organises resources, assumes financial risks, and pursues new business ventures, often introducing innovations in production or management.

This group included factory founders, merchant-capitalists, and innovators who reorganised work to achieve greater efficiency and output.

Entrepreneurs encouraged the transition from small-scale artisanal workshops to more systematic and coordinated production methods.

Organised Production and the Factory System

The rise of organised production redefined how goods were manufactured. Instead of relying on scattered household labour, entrepreneurs concentrated workers, tools, and processes in centralised locations. This allowed for tighter control of quality, supervision, and workflow.

The Move from Artisan Workshops to Coordinated Production

Before the market revolution, many goods were produced through artisanal craft systems, where skilled workers handled most stages of production. Entrepreneurs introduced a different model by breaking down production into specialised tasks.

Individual workers performed narrowly defined roles.

Production stages were arranged to maximise output.

Supervision increased as managers coordinated each step.

This systematic approach laid the foundation for early American factories and supported mass production.

New power-driven textile machinery such as the power loom made it efficient to centralise production in large buildings rather than rely on scattered household spinning and weaving.

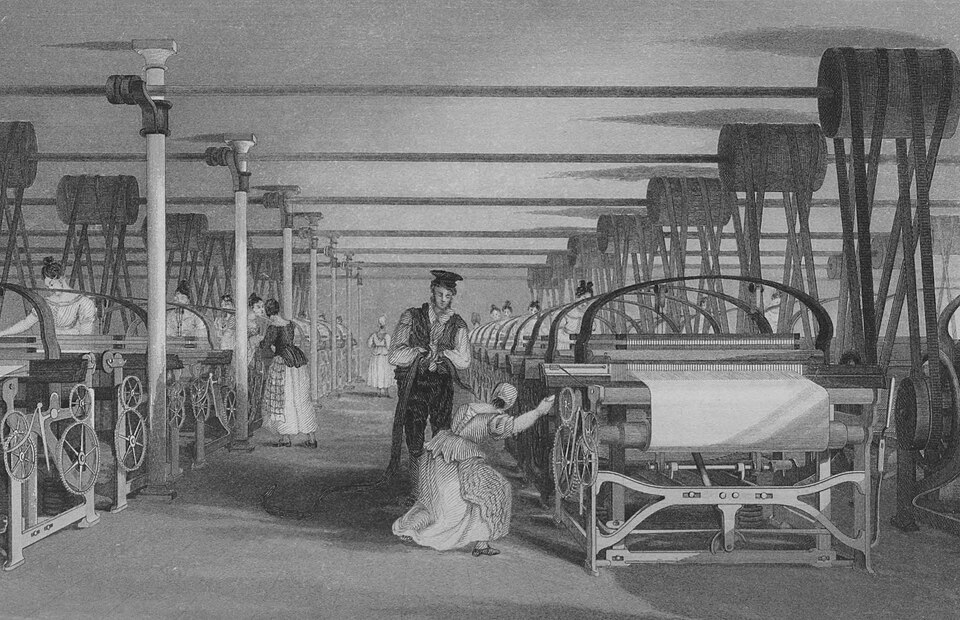

This engraving of an 1830s power-loom weaving room shows how mechanised textile production concentrated many machines and workers into one supervised space. The overhead drive shafts distribute power from a central source, enabling dozens of looms to run simultaneously. Although based on a British mill, the factory layout closely mirrors the organised textile production adopted by early American entrepreneurs. Source.

The Lowell System and Workforce Organisation

One of the most influential entrepreneurial innovations was the Lowell system, introduced in New England textile mills during the 1820s and 1830s. Entrepreneurs like Francis Cabot Lowell and the Boston Associates created large, integrated mills that combined spinning and weaving under one roof.

Integrated mill: A production facility that carries out multiple stages of manufacturing within a single complex, reducing transport time and increasing efficiency.

These mills employed young women—known as Lowell mill workers—under a regimented labour system that included boardinghouses, strict schedules, and company oversight. Entrepreneurs believed this model would ensure a disciplined, reliable workforce while promoting a reputation for moral supervision.

In Massachusetts, Francis Cabot Lowell and the Boston Associates developed the Waltham–Lowell system, combining spinning, weaving, and finishing in a single, water-powered mill complex staffed by young women workers.

This photograph of the Boott Cotton Mill in Lowell shows how American textile entrepreneurs concentrated standardised machinery in one factory to achieve highly organised production. The long rows of identical looms highlight the scale and uniformity of the Waltham–Lowell system. Although photographed later, the layout closely reflects the industrial environment created by early nineteenth-century mill owners. Source.

The Lowell system influenced other manufacturing sectors by demonstrating the advantages of combining mechanised processes with structured labour management.

Technological Innovation and Entrepreneurial Vision

Entrepreneurs were often among the earliest adopters of new technologies that enhanced productivity and reduced labour costs. Their decisions to invest in machinery reshaped production and encouraged a shift away from manual techniques.

Machinery and Specialisation

Innovations such as water-powered spinning frames, power looms, and later steam power allowed entrepreneurs to expand output and reduce reliance on skilled artisans.

Machines standardised production quality.

Mechanisation enabled longer operating hours and faster production cycles.

Specialised machine operators replaced traditional craft roles.

These changes created a more disciplined and predictable form of production, enabling entrepreneurs to coordinate larger and more complex business operations.

Interchangeable Parts and Organised Manufacturing

The development of interchangeable parts, associated with figures like Eli Whitney, supported the rise of organised production by allowing standardised components to be mass-produced.

Interchangeable parts: Uniform, standardised components that can be substituted for one another during assembly or repair.

This innovation reduced assembly times and made repair work more efficient. It also encouraged entrepreneurs to adopt assembly-line techniques, where workers performed repetitive tasks using pre-made components.

These processes allowed firms to scale production in ways that were not possible under the artisanal model.

Expanding Market Relationships

Entrepreneurs not only reorganised production but also helped cultivate wider market networks. Their business strategies encouraged regional interdependence and increased commercial activity.

Coordination of Supply Chains

Entrepreneurs helped structure early American supply chains by linking raw material sources, factories, and distribution networks.

Textile producers relied on Southern cotton, Northern mills, and urban merchants.

Improved transportation—canals, turnpikes, and later railroads—broadened market reach.

Entrepreneurs developed long-term relationships with suppliers and buyers.

These networks facilitated more predictable production cycles and strengthened ties between regions.

Credit, Investment, and Business Expansion

Entrepreneurs also contributed to financial growth by engaging in credit networks and attracting investment. They relied on banks, private investors, and merchant partnerships to secure funds for machinery, labour, and expansion.

Credit: The ability to borrow funds with the expectation of repayment, enabling businesses to invest before profits are realised.

This use of credit allowed entrepreneurs to scale their operations more quickly, creating larger and more integrated firms.

These financial practices contributed to the broader development of American capitalism, reinforcing the shift toward organised, market-oriented production in the early nineteenth century.

FAQ

Textiles were among the easiest industries to mechanise, and British precedents provided proven models that American investors could replicate. Cotton supplies from the American South also made textile production particularly profitable.

Entrepreneurs viewed textiles as a low-risk entry point for experimenting with factory systems, mechanised equipment, and regimented labour processes. Success in textiles then encouraged expansion into other manufacturing sectors.

Early entrepreneurs relied on a mixture of personal wealth, merchant partnerships, and emerging banking institutions. Many obtained credit from commercial banks that were expanding their lending activities in growing urban centres.

Some large projects, such as the Lowell mills, were financed through joint-stock arrangements, allowing multiple investors to share risk and pool resources. These financial innovations enabled rapid scaling of manufacturing ventures.

Factory owners implemented structured daily schedules, close supervision, and clear divisions of labour. These strategies reduced downtime and made production more predictable.

Additional techniques included:

Timekeeping systems to regulate work hours

Rules governing conduct in boardinghouses

Use of overseers to monitor productivity

Together, these practices created a controlled environment that supported large-scale production.

Entrepreneurs often built entire communities around their factories, especially in places like Lowell, Waltham, and Paterson. They invested in housing, churches, shops, and schools to attract and retain a stable workforce.

These towns became early examples of planned industrial communities. Their design reflected both economic goals—such as ensuring a reliable labour supply—and moral aims, including maintaining social order.

Entrepreneurs confronted resistance from skilled artisans who feared displacement. Mechanised production also required large initial investment in machinery and infrastructure, creating financial risks.

Other difficulties included:

Securing a disciplined workforce willing to adapt to factory routines

Ensuring adequate power sources, such as water or steam

Establishing steady supply chains for raw materials

Despite these challenges, the long-term profitability of factory production encouraged continued entrepreneurial expansion.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which early nineteenth-century entrepreneurs contributed to the rise of organised production in the United States, and briefly explain how it changed manufacturing.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks.

1 mark for identifying a specific entrepreneurial action (e.g., adoption of power-driven machinery, creation of integrated mills, introduction of task specialisation).

1 mark for explaining how the action altered production processes (e.g., replaced artisan methods, concentrated labour in factories).

1 mark for linking the change to broader shifts toward organised or large-scale manufacturing.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which technological innovation shaped the strategies and influence of entrepreneurs during the early stages of the market revolution.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks.

1 mark for presenting a clear thesis that addresses the extent of technological influence.

1–2 marks for describing specific technological developments used by entrepreneurs (e.g., power looms, water-powered spinning frames, interchangeable parts).

1–2 marks for analysing how these technologies enabled entrepreneurs to reorganise production, expand output, or reduce reliance on skilled labour.

1 mark for considering wider implications, such as expansion of factory systems, growth of investment networks, or increased market integration.