AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rising Southern cotton production and Northern manufacturing, banking, and shipping strengthened national and international commercial ties.’

Cotton’s expansion during the early nineteenth century reshaped America’s economy, linking Southern plantations to Northern industry and international markets, transforming regional relationships and commercial networks.

The Cotton Economy in the Early Nineteenth Century

Southern cotton production grew rapidly after 1800, transforming the region into the world’s leading supplier of raw cotton. Technological and market forces positioned cotton at the center of American economic life, reshaping relationships between regions and integrating the United States more deeply into global commercial systems. This transformation also made cotton the backbone of the Southern economy, entrenching slavery as a labor system essential to plantation profits and fueling national political debates.

The Role of the Cotton Gin and Plantation Expansion

The rapid expansion of cotton production depended heavily on Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, which enabled faster processing of short-staple cotton and allowed cultivation in a wider range of climates. This innovation stimulated large-scale plantation growth across the Deep South.

The cotton gin increased the profitability of short-staple cotton.

Planters expanded westward into fertile lands in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and eastern Texas.

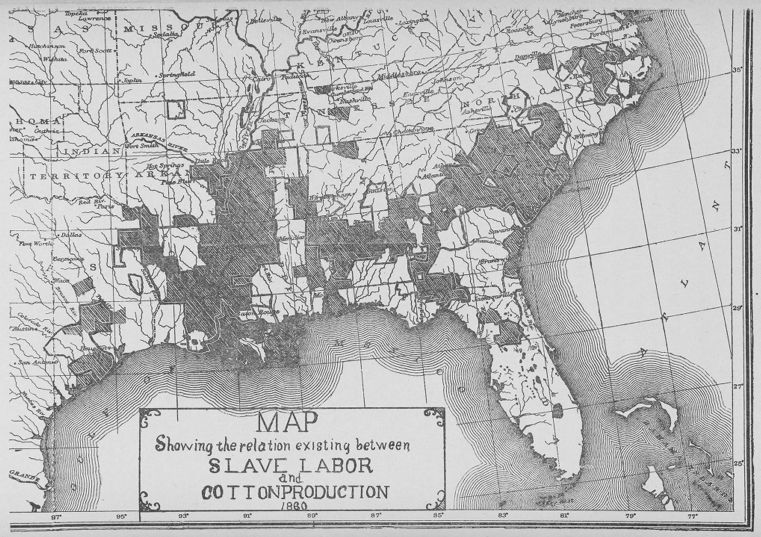

This map shows the relationship between slave labor and cotton production in 1860, illustrating how cotton agriculture and slavery spread into the Deep South. It reflects plantation expansion patterns that developed during 1800–1848. The date is slightly beyond Period 4 but represents the culmination of earlier trends. Source.

Cotton became the dominant Southern export commodity and the foundation of the region’s wealth.

As planters acquired more land, the demand for labor intensified. Because the plantation system relied on enslaved labor for clearing fields, cultivating cotton, and ginning the fiber, the growth of cotton production contributed directly to the forced migration of enslaved people from the Upper South to the Lower South.

Regional Interdependence and the Rise of Integrated Commerce

The syllabus emphasizes that rising Southern cotton production strengthened national and international commercial ties in conjunction with Northern manufacturing, banking, and shipping. Cotton was not simply a Southern product; it fueled a fully interconnected economic system.

Northern Manufacturing and Financial Networks

Northern industrialization accelerated in tandem with Southern cotton growth. Textile mills in New England and the Mid-Atlantic relied on Southern cotton as their primary raw material. These factories transformed raw cotton into cloth, which was then sold domestically and internationally.

Industrial capitalism: An economic system in which production is organized in factories, financed by banks, and driven by wage labor and market demand.

Northern financiers and commercial houses played an equally important role by providing credit, insurance, and market access for Southern planters.

Northern banks supplied loans that enabled plantation expansion.

Insurance firms in coastal cities underwrote the risk of shipping cotton across the Atlantic.

Merchant houses coordinated transportation, negotiated prices, and facilitated connections with buyers in Britain and Europe.

These networks made the North deeply dependent on Southern cotton profits while giving the South access to global markets it could not reach alone.

A normal sentence continues the explanation of these financial ties, emphasizing how they reinforced commercial links across regions.

Shipping, Trade Centers, and the Growth of Port Cities

Cotton linked American port cities into a powerful commercial chain.

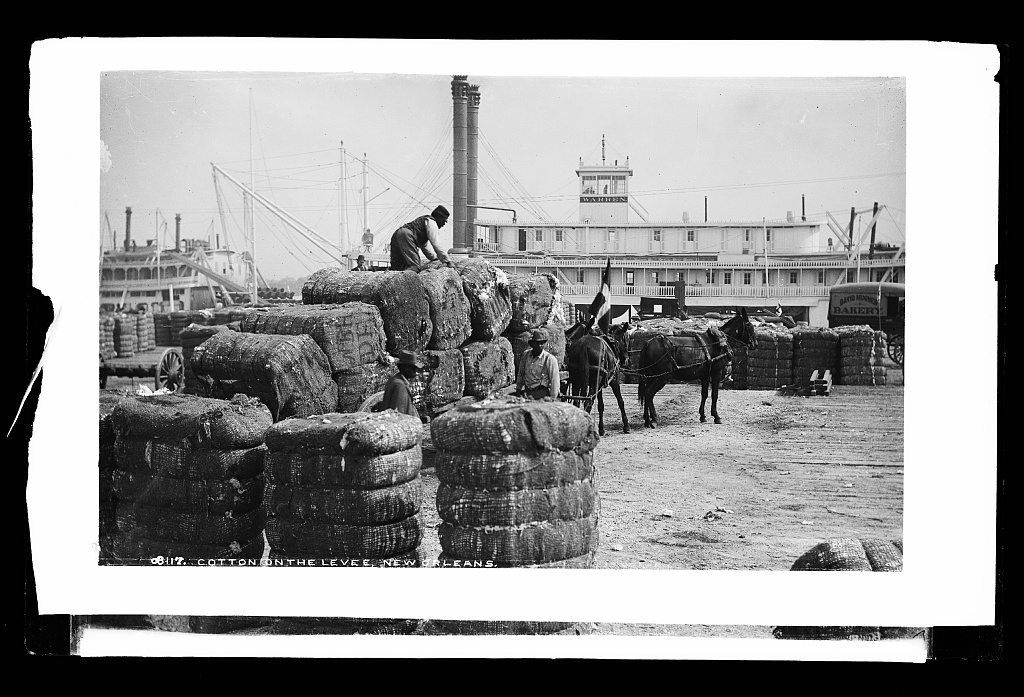

This photograph shows cotton bales stacked along the New Orleans levee as workers and steamboats prepare shipments. It illustrates how Southern cotton flowed to major ports before moving to Northern and European markets. The photo is from the later nineteenth century but depicts patterns established during 1800–1848. Source.

New Orleans, Charleston, and Mobile served as major cotton-exporting centers, while New York emerged as the dominant national port due to its extensive shipping networks and financial services.

This painting shows large steamboats at the New Orleans waterfront, with enslaved laborers and workers handling cargo under white supervision. It highlights how port facilities and river transport concentrated the wealth of the cotton trade and linked plantation regions to wider markets. The image includes broader social details not required by the syllabus but helps visualize the commercial activity of the mid-nineteenth century. Source.

This system strengthened the North’s position within the national economy even as the raw material originated in the South.

International Demand and the Global Cotton Market

Britain’s Industrial Revolution intensified global demand for cotton. British textile factories required enormous quantities of raw cotton, and the American South became their most reliable supplier.

Transatlantic Economic Networks

American cotton exports flowed primarily to Britain, but also to France and other European nations. As a result, the United States became deeply integrated into a global commercial economy.

British industrial expansion increased demand for American cotton.

U.S. cotton exports accounted for over half of all American exports by the 1830s.

International investors became indirectly tied to the U.S. plantation economy through credit and commercial networks.

The profitability of cotton tied the South to global markets in ways that heightened both its economic importance and its vulnerability to international price fluctuations.

Social and Political Implications of Cotton Commerce

As cotton profits rose, planters consolidated power within Southern society. Wealthier plantation owners dominated political institutions, shaping laws that protected slavery and encouraged land acquisition.

Entrenchment of Slavery

Cotton’s economic centrality made slavery indispensable to Southern elites. The belief that cotton required enslaved labor justified political defenses of the institution and deepened sectional tensions.

Cotton profits strengthened proslavery ideology.

Enslaved laborers performed the vast majority of cotton cultivation work.

Westward expansion enabled the spread of both cotton and slavery.

National Impacts

The integration of cotton into national commerce influenced political debates about tariffs, banking, territorial expansion, and internal improvements. Although cotton unified the national economy, it also contributed to rising sectional divisions that would dominate later political conflicts.

Cotton production, therefore, was not simply an agricultural activity; it was an economic engine that bound regions together while highlighting the profound contradictions of the early nineteenth-century United States.

FAQ

Cotton prices fluctuated sharply due to changes in global demand, harvest yields, and competition from other cotton-producing regions. These variations meant that profits could not be guaranteed even in years of high production.

Because most planters operated on credit, falling prices made it difficult to repay loans, creating cycles of debt. Merchants and factors often tightened credit in response, deepening financial vulnerability across the plantation economy.

Cotton factors acted as intermediaries who sold cotton on behalf of planters, typically operating out of major port cities like New Orleans, Mobile, and Charleston.

They arranged shipping, negotiated prices, secured credit, and provided market intelligence. By managing these transactions, they connected individual planters to distant buyers in Britain and Europe, helping integrate Southern cotton into international trade networks.

New York’s extensive banking sector, insurance services, and shipping networks allowed the city to control financial and logistical aspects of the cotton trade.

The Erie Canal strengthened New York’s links with domestic markets, and its merchant houses forged strong connections with British textile firms. As a result, most cotton exports passed through New York’s financial infrastructure even when physically shipped from Southern ports.

Improvements in steamboat design allowed for faster, more reliable river transport, which helped move cotton from inland plantations to Gulf and Atlantic ports more efficiently.

Enhanced coastal and transatlantic shipping, including better hull design and navigation tools, reduced travel times and increased shipment volumes. These developments helped integrate regional markets and strengthened the United States’ commercial presence abroad.

Cotton’s profitability elevated wealthy planters to the top of Southern society, giving them disproportionate political and economic influence.

Below them were smaller slaveholders and non-slaveholding white farmers whose status was shaped by proximity to plantation wealth. Enslaved people, who formed the labour backbone of the cotton economy, occupied the lowest rung and faced severe restrictions on movement, autonomy, and family life.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which rising Southern cotton production contributed to the growth of national commercial connections in the early nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid link between cotton production and wider commercial activity (e.g., cotton feeding Northern textile mills).

1 mark for explaining how this link functioned (e.g., Northern manufacturers relied on Southern raw materials, creating interregional dependence).

1 mark for providing a specific detail or consequence (e.g., New York merchants dominated cotton shipping; banks and insurers supported the trade; cotton became a major export commodity).

(4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which the growth of cotton production between 1800 and 1848 contributed to interregional economic interdependence within the United States. In your answer, consider links between agriculture, industry, and commerce.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1–2 marks for describing economic connections between the Southern cotton economy and Northern textile manufacturing.

1–2 marks for analysing the role of financial and commercial institutions, such as banks, insurers, or merchant houses, in linking regions.

1–2 marks for evaluative judgement about the extent of interdependence, supported with specific evidence (e.g., cotton as a leading export; Northern dominance of shipping; reliance on British textile demand).