AP Syllabus focus:

‘After Reconstruction, plantation owners kept most land; many freedpeople sought land ownership but rarely achieved self-sufficiency.’

After emancipation, freedpeople sought autonomy and stability through landownership and new labor systems, but structural inequalities, white resistance, and limited federal intervention constrained meaningful economic independence.

Land, Freedom, and Postwar Realities

The end of slavery in 1865 transformed the Southern economy and raised urgent questions about who would control land, labor, and agricultural production. Landownership—long associated with political independence and economic security—became a central aspiration for formerly enslaved African Americans. Many believed that real freedom required access to property, not simply liberation from bondage. Yet the Southern landholding structure remained deeply unequal, and most plantation owners retained their estates despite widespread wartime destruction and federal occupation.

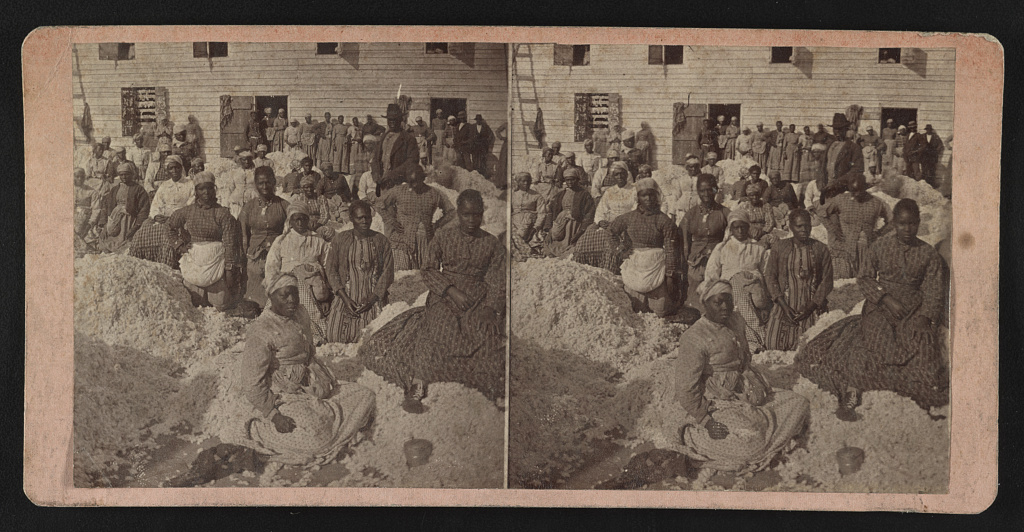

Freedom on the plantation, c. 1863–1866. African American women laborers and a white overseer process cotton, illustrating how plantation work continued even as slavery ended. The image includes extra visual detail about clothing styles and the built environment that is not required by the syllabus but helps students imagine post-emancipation labor conditions. Source.

Freedpeople’s Aspirations for Landownership

Freedpeople advanced a vision of freedom tied to autonomy over their labor and household economies. Their demand for land stemmed from generations of coerced labor, in which enslaved people had produced immense wealth but possessed no legal claim to the fields they worked.

Autonomy: The ability of individuals or communities to make independent decisions about labor, residence, and economic arrangements without coercion.

Freedpeople expected the federal government—especially the Union Army and the Freedmen’s Bureau—to support land redistribution. Rumors of “forty acres and a mule” spread widely after experiments in confiscation along the South Carolina and Georgia coasts. Although some freed families temporarily held land during the war, most allocations were reversed after President Andrew Johnson’s lenient Reconstruction policies restored property to former Confederates. As a result, aspirations for landownership increasingly collided with political retreat from radical reform.

Retention of Land by White Southerners

White landowners benefitted from federal policies that prioritized property rights over transformative social change. After Reconstruction, courts and political leaders insisted on maintaining the prewar landholding order, even as the labor system formally shifted from slavery to wage or tenancy arrangements. White elites’ control over land became the foundation for new systems of economic subordination.

How Landholding Structures Shaped Regional Power

The preservation of large estates meant landowners continued to dominate agricultural production and regional politics. Their ability to determine labor terms severely constrained freedpeople’s options.

Credit access remained limited, forcing African Americans to rely on high-interest loans or merchant advances.

Mobility was suppressed through vagrancy laws and labor contracts that restricted leaving plantations.

Violence and intimidation reinforced economic dependence, especially in rural counties where federal oversight waned.

These conditions created a post-emancipation society in which the legal end of slavery did not translate into economic equality.

Labor Systems in the Post-Emancipation South

Without land of their own, most freedpeople became dependent on labor arrangements that preserved plantation agriculture while avoiding the appearance of forced labor. The central question became how to organize work in a system marketed as free but shaped by deep power imbalances.

Wage Labor and Its Limitations

Wage labor theoretically offered flexibility, but wages were often extremely low, paid irregularly, or supplemented with deductions for housing and supplies. Many white planters opposed yearlong wage contracts, fearing they deprived them of the tight control once ensured by slavery. Seasonal agreements left freedpeople vulnerable to exploitation.

Wage Labor: A labor system in which workers sell their labor for monetary payment under contractual terms.

Although wage labor represented a legal shift from slavery, it rarely provided the income necessary for freedpeople to accumulate savings or purchase land. Ongoing racial discrimination in courts and local governments further limited opportunities to contest unfair practices.

Emergence of Tenancy and Partial Control of Labor

Some freedpeople tried to negotiate tenancy agreements, renting small plots for fixed payments or shares of crops. Tenancy allowed a degree of household autonomy because families could control daily work rhythms and choose which crops to plant. However, landowners insisted on staples such as cotton, which maintained the region’s dependence on a volatile international market.

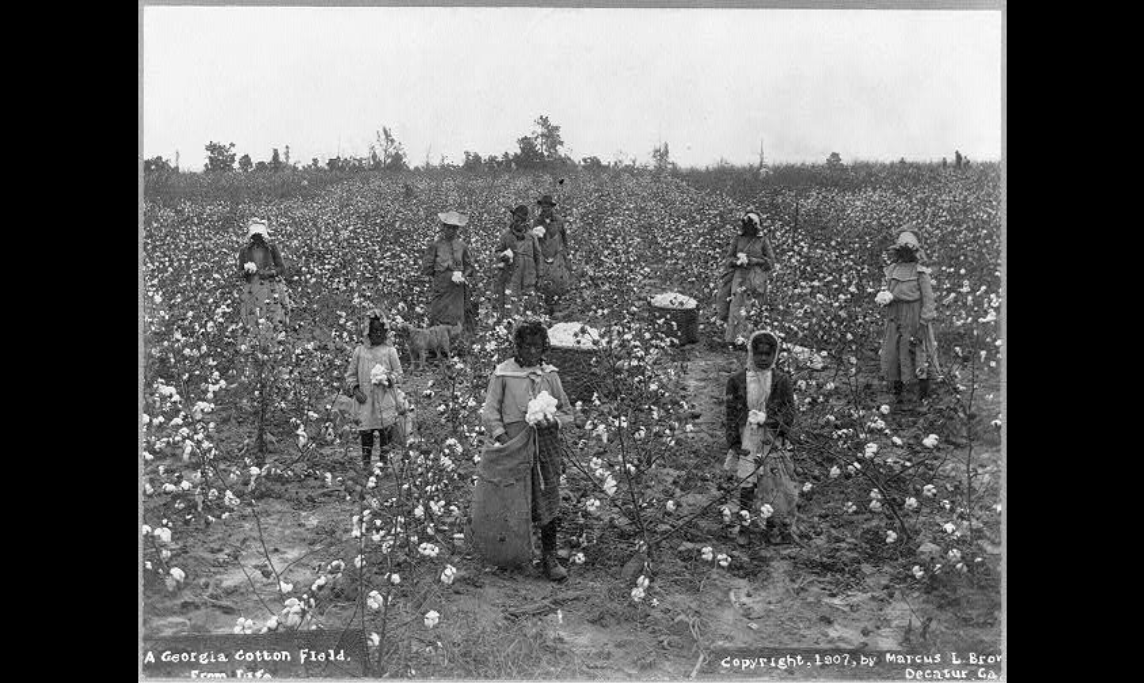

African American workers pick cotton in a Georgia field, c. 1907. The scene demonstrates how Black labor remained concentrated in cotton agriculture long after the Civil War. The later date extends slightly beyond the syllabus period but helps students see the long-term endurance of post-emancipation land and labor patterns. Source.

Why Self-Sufficiency Remained Rare

Despite tremendous effort, most freedpeople never achieved economic independence. Several interconnected barriers prevented widespread landownership:

Structural and Economic Obstacles

The collapse of land redistribution ensured white ownership remained the norm.

Unfair credit systems institutionalized debt that trapped families in cycles of dependency.

Agricultural prices fluctuated, making it difficult for laborers to accumulate surplus income.

State and local governments prioritized the interests of white landowners, not agricultural workers.

Social and Political Constraints

Violence from groups like the Ku Klux Klan and everyday acts of coercion curtailed African Americans’ ability to assert economic rights. Many who attempted to leave plantations or negotiate better terms faced retaliation. Political rollback after Reconstruction further weakened federal protection, allowing Southern elites to reassert dominance over regional labor markets.

Continuing Impact of Unequal Land Distribution

The post-emancipation land and labor structure had long-term consequences for African American communities. Persistent landlessness restricted educational opportunities, limited political influence, and reinforced social hierarchies.

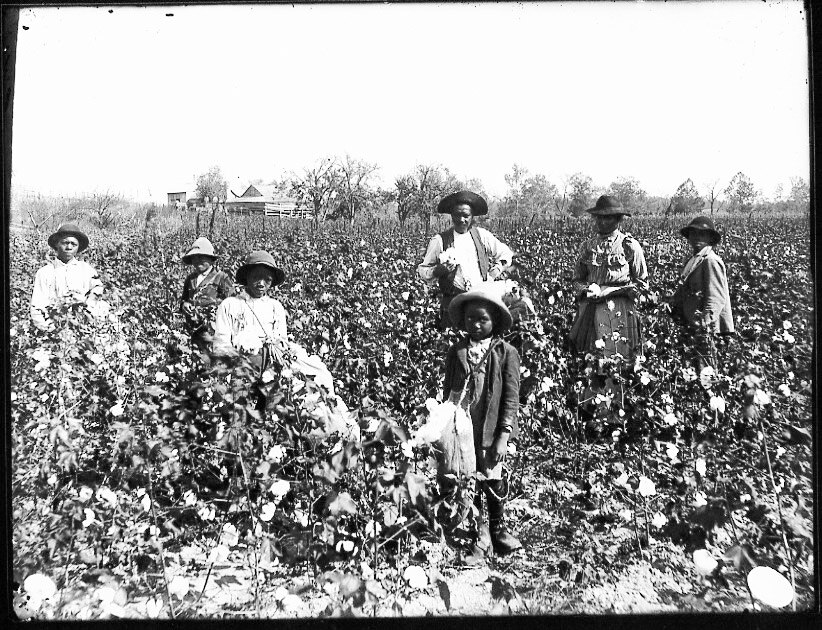

Black cotton farmers stand among cotton plants, likely in the late nineteenth century. The image highlights how entire families, including children, labored in cotton agriculture even after slavery ended. The photograph includes additional contextual detail, such as buildings in the background, that is not required by the syllabus but helps illustrate rural life in the post-emancipation South. Source.

FAQ

Freedpeople generally defined economic freedom as the ability to control their own labour, live independently from white supervision, and ultimately acquire land for family security.

White Southern landowners, however, equated economic stability with maintaining a disciplined agricultural workforce and preserving large estates. Their priorities centred on continuity of production rather than expanding labourers’ autonomy.

These contrasting visions created constant conflict over work discipline, wages, tenancy terms, and mobility.

The Bureau faced limited funding, political opposition from President Andrew Johnson, and entrenched resistance from white landowners who demanded restoration of confiscated property.

Its authority was also temporary and unevenly enforced, leaving many local agents unable to protect freedpeople’s claims.

Without sustained federal backing, most wartime land redistribution orders were reversed before freed families could secure permanent titles.

Many freedpeople sought seasonal or migratory work to bargain for higher wages or escape abusive employers. Moving also allowed families to reconnect after slavery’s separations.

However, vagrancy laws, labour contracts, and racial violence sharply curtailed mobility.

• Employers used legal and extralegal pressure to tie labourers to plantations.

• County officials often arrested African Americans travelling without written proof of employment.

These restrictions reduced freedpeople’s leverage in negotiating better labour terms.

Freedwomen often sought to limit field work and prioritise domestic labour, viewing household control as central to freedom. Many expected men’s wages or tenancy earnings to support the family.

Landowners rejected these gender norms, insisting that women continue to labour in fields to maintain production.

This clash created ongoing disputes, with planters using contract terms and coercion to push women into agricultural work, while freed families tried to assert new domestic roles.

Cotton was the most profitable export crop, and landowners structured tenancy contracts to require its cultivation, leaving little room for subsistence farming.

Merchants provided credit mainly for cotton seed and supplies, reinforcing dependence on a single crop.

Because cotton prices were unstable, families struggled to accumulate savings, yet shifting to food crops was rarely permitted under tenancy terms or plantation expectations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one major reason why freedpeople struggled to acquire land after emancipation.

Question 1

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., most land remained in the hands of white plantation owners).

• 2 marks: Gives a reason with brief elaboration (e.g., federal policies restored confiscated land to former Confederates, preventing redistribution).

• 3 marks: Provides a clear and accurate explanation showing understanding of structural obstacles (e.g., retention of land by white elites, lack of government-backed redistribution, and restricted access to credit that prevented African Americans from purchasing property).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how post-emancipation labour systems in the South limited African Americans’ ability to achieve economic independence in the period after Reconstruction. Refer to specific features of wage labour, tenancy, or credit systems in your answer.

Question 2

• 4 marks: Provides a general explanation of how labour systems limited economic independence, with at least one accurate reference to wage labour, tenancy, or credit systems.

• 5 marks: Offers a more detailed explanation, referring to at least two labour systems and linking them to restricted autonomy, persistent dependency, or limited opportunities for land purchase.

• 6 marks: Gives a well-developed, clearly structured explanation referencing multiple systems (wage labour, tenancy, credit), demonstrating strong understanding of how these mechanisms reinforced economic dependence and prevented self-sufficiency.