AP Syllabus focus:

‘Segregation, violence, Supreme Court decisions, and local political tactics progressively stripped away African American rights after Reconstruction.’

After Reconstruction’s initial gains for African Americans, Southern leaders and white supremacist organizations orchestrated a systematic rollback of rights through segregation, racial violence, and political exclusion, reshaping regional power structures and undermining federal protections.

The Retreat from Reconstruction-Era Progress

Southern resistance to racial equality hardened during the late nineteenth century as white elites sought to restore prewar social hierarchies. Federal withdrawal from the South after 1877 signaled a weakening commitment to enforcing civil rights legislation, allowing local and state governments to implement measures that curtailed the political and social influence of African Americans.

The Rise of Jim Crow Segregation

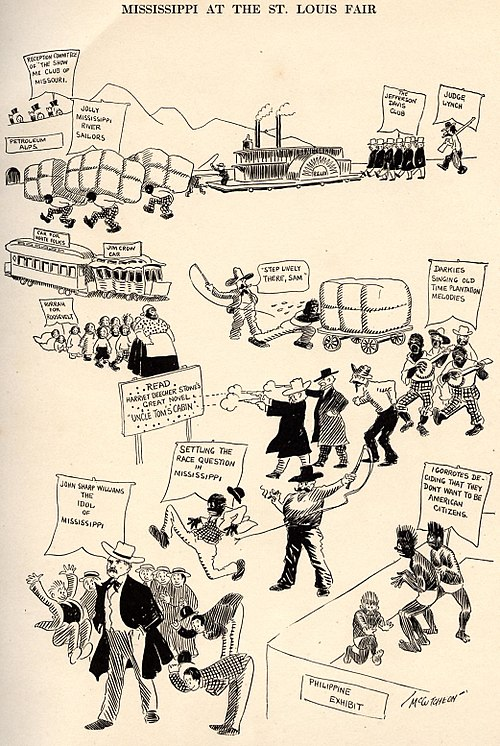

Jim Crow laws, a network of state and local statutes enforcing racial separation, became a primary mechanism of structured discrimination. Legislators argued these laws preserved social order, but in practice they institutionalized inequality in nearly every aspect of daily life.

This photograph from the Dougherty County Courthouse shows segregated “white” and “colored” drinking fountains during the Jim Crow era. The visual contrast reveals how segregation penetrated everyday infrastructure and reinforced racial inequality. Although taken later in the twentieth century, it reflects the long-term legacy of discriminatory systems rooted in the post-Reconstruction period. Source.

Jim Crow laws: State and local statutes enforcing racial segregation and unequal treatment in public facilities, transportation, housing, and education.

Segregation developed unevenly across the South before solidifying into a rigid system by the 1890s. Its expansion was shaped by several factors:

The desire of white political leaders to prevent interracial political alliances.

A social ideology claiming that racial mixing would destabilize Southern society.

Economic motives to suppress Black labor competition and maintain a low-wage workforce.

These dynamics contributed to a narrowing of African American opportunities as separate facilities were deliberately underfunded and inferior.

Violence as a Tool of Social and Political Control

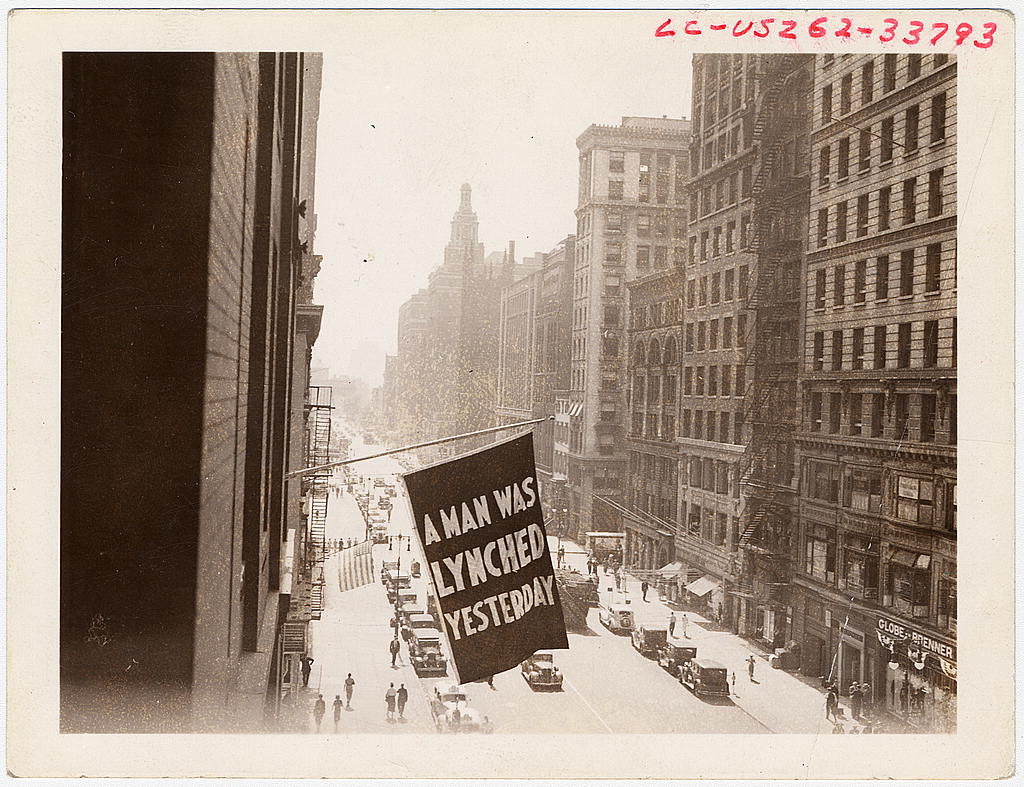

Racial violence surged during this era, functioning as both intimidation and punishment. White supremacist groups and local mobs engaged in lynching, assaults, and property destruction to enforce racial hierarchies and suppress Black civic participation.

This photograph shows a banner displayed by the NAACP to draw national attention to the frequency and severity of lynching. It underscores how racial violence operated as a tool of intimidation while highlighting organized efforts to document and protest these abuses. The urban setting provides additional historical context beyond the syllabus but reinforces the national reach of anti-lynching activism. Source.

Lynching: Extrajudicial killing—typically by a mob—used to terrorize African Americans and reinforce racial dominance without legal accountability.

Acts of violence often coincided with periods of African American political activism, demonstrating the connection between racial terror and efforts to regain white control. Newspaper reports and political speeches frequently normalized or justified such violence, allowing perpetrators to operate with impunity.

Federal Disengagement and Judicial Decisions

As national priorities shifted, federal authorities retreated from enforcing Reconstruction amendments. Judicial rulings played a crucial role in weakening civil rights guarantees, providing constitutional cover for segregation and restricted participation.

The Civil Rights Cases (1883) struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to state actions, not private discrimination. This interpretation narrowed federal capacity to challenge racial inequality.

The most far-reaching decision, however, emerged in 1896 with Plessy v. Ferguson. The Supreme Court upheld segregation under the doctrine of “separate but equal,” enabling states to expand discriminatory laws and severely limiting Black access to fair public services.

This cartoon satirizes Mississippi’s entrenched segregation system by depicting separate train cars labeled for white and Jim Crow passengers. It reflects the ideology of “separate but equal” that gained legal legitimacy through Plessy v. Ferguson. The reference to the 1904 World’s Fair adds broader national context beyond the syllabus but helps illustrate how segregation was widely recognized and critiqued. Source.

Political Rollback: Disenfranchisement and Local Tactics

Even as segregation reshaped public life, Southern governments targeted African American voting rights to eliminate Black political influence. Disenfranchisement was not instantaneous but developed through layers of legislative and administrative restrictions.

Key methods included:

Poll taxes, which required payment to vote and disproportionately burdened poor African Americans.

Literacy tests, designed to be arbitrarily administered to exclude Black citizens.

Grandfather clauses, allowing white voters to bypass new restrictions if their ancestors had voted prior to the Civil War.

White primaries, in which political parties—treated as private organizations—restricted participation to white voters only.

Poll tax: A fee imposed as a prerequisite for voting, used to disenfranchise economically disadvantaged citizens, especially African Americans.

These tactics effectively removed African Americans from the electorate. Because elections often hinged on primaries in one-party Democratic states, exclusion from the nominating process silenced Black political voices.

Normal social and political channels thus became closed to African Americans, entrenching single-party rule and consolidating white supremacy at the state level.

Social Consequences and the Entrenchment of White Supremacy

The combined impact of segregation, violence, and political disenfranchisement shaped a racial order that lasted well into the twentieth century. African Americans faced barriers in:

Education, due to underfunded and inadequate segregated schools.

Employment, as segregated labor markets limited opportunities for advancement.

Legal protection, since courts often neglected or dismissed cases involving Black victims.

Civic life, where exclusion from juries and public office curtailed influence.

This systematic repression resulted in widespread migration as many African Americans sought new opportunities outside the South. Despite these oppressive conditions, individuals and communities continued to resist through advocacy, institution building, and participation in civil rights organizations.

FAQ

Local police forces often enforced segregation laws unevenly, targeting African Americans for violations while ignoring white infractions. Officers were also frequently complicit in racial violence, either by failing to intervene in mob attacks or by actively assisting white vigilantes.

Sheriffs and constables played a key role in restricting Black mobility by selectively arresting African Americans under vagrancy laws, which kept them economically vulnerable and compliant.

For poorer white Southerners, racial hierarchy offered psychological and social status, reinforcing the belief that political exclusion of African Americans protected their place in society.

Economic motives also mattered: restricting Black political influence ensured labour remained cheap and competition limited. Political leaders effectively used racial fear to rally support for policies that benefited elite power structures.

Southern newspapers often depicted African Americans as threats to public order, legitimising discriminatory laws and justifying violence. Sensationalised crime reporting, especially around alleged assaults by Black men, fuelled white anxieties.

Editorial cartoons and opinion pieces reinforced stereotypes, framing segregation as a natural and necessary part of Southern life. This constant messaging normalised prejudice and undermined advocacy for equal rights.

Black citizens faced hostile courts where judges, juries, and police overwhelmingly supported white interests. African Americans were rarely allowed to serve on juries, making fair trials nearly impossible.

Legal appeals were often blocked by discriminatory procedures, and Black victims of violence seldom saw perpetrators prosecuted. This systemic exclusion reduced trust in public institutions and reinforced white dominance.

Political leaders prioritised national reconciliation, believing strong enforcement of African American rights would reignite sectional conflict. Northern voters grew increasingly indifferent to Southern racial issues, weakening pressure on Congress.

The Supreme Court’s narrow interpretation of federal power made intervention legally difficult, while Presidents feared alienating Southern political allies. Together, these factors created a permissive environment for state-level oppression.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which racial violence supported the system of segregation that developed in the South after Reconstruction.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a relevant form of violence (e.g., lynching, mob attacks, intimidation).

1 mark for explaining how this violence reinforced segregation (e.g., by deterring African Americans from challenging discriminatory laws or customs).

1 mark for linking violence to broader political or social control (e.g., preventing African American civic participation or maintaining white supremacy).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the factors that contributed to the political disenfranchisement of African Americans in the South between the end of Reconstruction and the early twentieth century.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying at least one formal legal restriction (e.g., poll tax, literacy test, grandfather clause, white primary).

1 mark for explaining how such restrictions functioned to limit African American voting.

1 mark for describing informal pressures or intimidation (e.g., violence, threats, job reprisals).

1 mark for linking disenfranchisement to wider social or political aims (e.g., maintaining Democratic one-party rule, upholding white supremacy).

1 mark for discussing federal disengagement or Supreme Court decisions that enabled restrictions (e.g., limited enforcement of the Reconstruction Amendments, permissive judicial rulings).

1 mark for overall analytical coherence, demonstrating a clear argument about why disenfranchisement succeeded.