AP Syllabus focus:

‘An exploitative, soil-intensive sharecropping system limited African Americans’ and poor whites’ access to land and economic independence in the South.’

Sharecropping emerged after the Civil War as a supposedly cooperative land-labor arrangement, yet it entrenched economic dependency, reinforced racial hierarchies, and reshaped Southern agriculture through intensive cotton cultivation.

The Origins of Sharecropping in the Post-Emancipation South

Sharecropping developed in the late 1860s as a compromise between formerly enslaved people seeking landownership and white planters seeking reliable labor after emancipation. With most land still controlled by white plantation owners, freedpeople lacked capital to purchase farms or supplies. Sharecropping appeared to offer autonomy, as families could choose work routines, negotiate contracts, and cultivate specific plots. In practice, however, the system created new forms of economic control.

The term sharecropping referred to laborers farming land they did not own in exchange for a share of the crop, usually one-third to one-half.

Sharecropping: A labor system in which tenant farmers worked a landowner’s property in return for a contractually defined portion of the harvested crop.

Although sharecropping resembled tenancy, it relied on deep inequalities in wealth and bargaining power. Accepted widely across the South by 1870, it tied both African American and poor white farmers to cycles of indebtedness.

How Sharecropping Contracts Functioned

Sharecropping contracts governed land use, labor expectations, and crop division, often written by landowners or local officials aligned with planter interests. Contracts shaped nearly every aspect of agricultural life.

Key Contract Features

Land Assignment: Croppers worked designated plots but lacked legal claim to them.

Supply Advances: Landowners or merchants provided tools, seed, food, and clothing on credit through the crop-lien system, which used future harvests as collateral.

Crop Division: At harvest, the landowner took a predetermined share, often leaving croppers with insufficient yields to pay debts.

Labor Requirements: Contracts often demanded long workdays, strict supervision, and compliance with plantation rules reminiscent of slavery-era control.

The crop-lien system became essential to sharecropping’s persistence. Credit was issued at high interest rates—sometimes exceeding 50 percent—and merchants could legally claim the first portion of harvested crops to settle outstanding debts.

Crop-lien system: A credit arrangement in which merchants or landowners lent supplies to farmers in exchange for legal claim to future crops until debts were repaid.

Merchants’ ability to seize crops meant farmers rarely escaped annual deficits. This system bound families to the same land year after year.

Economic Dependency and the Limits of Mobility

Sharecropping severely limited economic independence, the central theme of the syllabus specification. Freedom from slavery did not translate into access to capital, markets, or credit on fair terms. Several structural factors deepened dependency.

Structural Forces Entrenching Poverty

Lack of Land Redistribution: Despite freedpeople’s demands for “forty acres and a mule,” federal policy returned most confiscated lands to ex-Confederates, ensuring laborers remained landless.

Single-Crop Economy: Cotton dominated Southern agriculture because it generated export profits. Yet monoculture heightened vulnerability to price fluctuations and soil depletion.

Debt Cycles: Annual borrowing for supplies pushed croppers into long-term indebtedness, reducing bargaining power and tying families to landowners or merchants.

Legal Frameworks: State laws criminalized vagrancy or breach of contract, allowing courts to coerce labor and protect landowner interests.

These factors made sharecropping not merely a labor arrangement but a regional economic structure that maintained racial inequality after Reconstruction. While some white farmers faced similar hardships, African Americans faced additional racial barriers, including discriminatory credit practices and the threat of violence if they attempted to leave or negotiate.

Social and Cultural Implications

Sharecropping shaped rural life, family labor patterns, and community organization across the South. Many families worked collectively, with women and children contributing labor during planting and harvesting seasons.

African American sharecropper Will Cole and his son pick cotton on rented land in North Carolina in 1939. The image illustrates family labor central to the sharecropping system. Their work in a cotton monoculture reflects the economic dependency described in the sharecropping and crop-lien system. Source.

Although croppers enjoyed limited autonomy in daily labor routines compared to slavery, their economic insecurity restricted broader social freedoms.

Constraints on Autonomy

Limited Mobility: Debt and annual contracts hindered relocation.

Educational Barriers: Families often kept children out of school during harvest months, slowing literacy gains.

Political Disempowerment: Economic dependence made sharecroppers vulnerable to intimidation, undermining Black political participation as Jim Crow laws expanded.

Sharecropping also influenced land use. Soil-intensive cotton farming caused erosion and nutrient exhaustion, further reducing yields and increasing dependence on borrowed supplies.

Regional Consequences for the Post-Reconstruction South

By the 1880s, sharecropping dominated the Southern agricultural economy.

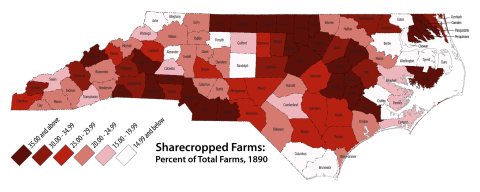

This choropleth map illustrates the proportion of sharecropped farms across North Carolina in 1890. Darker counties represent high reliance on sharecropping, demonstrating how tenancy structures took hold across the South. Although specific to one state, it exemplifies regional patterns of economic dependency. Source.

Its exploitative nature kept the region economically stagnant, discouraging mechanization and investment in diversified farming. The system preserved planter dominance while masking inequality under the guise of contractual freedom.

Long-Term Effects

Perpetuated Land Concentration: Most arable land remained in the hands of white elites.

Reinforced Racial Hierarchies: Economic control functioned alongside segregation, violence, and disfranchisement.

Delayed Modernization: Reliance on manual labor and cotton monoculture slowed industrial growth and broader economic development.

Together, these dynamics reveal how an “exploitative, soil-intensive sharecropping system” curtailed land access and blocked economic independence for African Americans and poor whites, fulfilling the syllabus emphasis on structural dependency in the post-Reconstruction South.

FAQ

In cotton regions, sharecropping contracts were typically stricter because cotton was highly profitable and required intensive labour, encouraging landowners to exert tighter control over work routines.

In regions focused on tobacco or mixed farming, arrangements could be slightly more flexible, with some tenants negotiating better terms or diversifying crops.

However, cotton-dominated areas retained the most entrenched debt cycles due to market volatility and higher costs of production.

Sharecroppers used informal community networks to share information about fair prices, dishonest merchants, and contract terms.

Some formed cooperative buying clubs to reduce reliance on local merchants, and others attempted seasonal migration to areas with better wages.

A few engaged in quiet acts of resistance such as working at slower paces or negotiating collectively, though these strategies carried risks of eviction or violence.

Landowners often prioritised short-term profit over long-term sustainability, viewing immediate returns from cotton as outweighing future soil fertility concerns.

Many believed labour was plentiful and replaceable, and they considered the system successful if it maintained social control and steady production.

Economic conservatism and lack of capital also contributed, as landowners resisted investing in diversification or fertilisation.

Merchants functioned as the primary source of credit, effectively acting as financial gatekeepers for sharecroppers and landowners alike.

Their control over prices, interest rates, and crop marketing often dictated whether farming families survived each season.

They also held social influence: alliances between merchants and large landowners reinforced existing power structures and limited opportunities for economic reform.

Both groups faced chronic debt, landlessness, and dependence on credit, which created similar economic hardships.

However, poor white farmers often had slightly better access to legal support, credit opportunities, or mobility, due to racial hierarchies that shaped everyday interactions.

Despite this, many remained trapped in the same exploitative system, illustrating how class and race interacted to reinforce Southern agricultural dependency.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify two ways in which the sharecropping system limited African Americans’ economic independence in the post-Reconstruction South.

Question 1

Award 1 mark for each valid way (up to 2).

Possible correct points include:

Sharecroppers lacked ownership of land, preventing accumulation of wealth. (1 mark)

High-interest credit and debt cycles trapped families in long-term financial dependency. (1 mark)

Merchants’ control over crop sales meant croppers rarely retained enough profit to become self-sufficient. (1 mark)

Reliance on cotton monoculture made farmers vulnerable to price fluctuations and soil depletion. (1 mark)

Any two of the above or equivalent.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how the crop-lien system contributed to long-term economic dependency among sharecroppers in the late nineteenth-century South. In your answer, refer to both African American and poor white farmers.

Question 2

Award marks according to the following criteria:

Identification of the crop-lien system and its basic function.

For example: noting that it provided supplies on credit using future crops as collateral. (1 mark)Explanation of how high interest rates and merchant control led to debt accumulation.

Must reference annual cycles of indebtedness. (1 mark)Discussion of how debt restricted mobility or bargaining power for sharecroppers.

May include inability to leave land or negotiate better terms. (1 mark)

Reference to racial dimensions, noting additional barriers faced by African Americans.

For example: discriminatory credit practices or threats of violence enforcing dependency. (1 mark)Inclusion of poor white farmers in the explanation, showing shared but unequal experiences of debt dependency.

Must indicate both common economic pressures and differences in treatment. (1 mark)

Answers may vary in wording, but they must address the structural nature of credit, debt, and labour relations in the sharecropping economy.