AP Syllabus focus:

‘Court decisions such as Dred Scott were meant to settle slavery in the territories, but ultimately increased sectional conflict rather than reducing it.’

The Dred Scott decision attempted to impose a national legal resolution on slavery in the territories, but instead deepened sectional polarization and exposed the limits of federal authority.

The Dred Scott Decision in Historical Context

The Dred Scott v. Sandford ruling of 1857 emerged in a moment of escalating national tension over territorial slavery. After the Kansas–Nebraska Act reopened sectional disputes by promoting popular sovereignty—the idea that territorial settlers should decide the status of slavery—the Supreme Court sought to impose a definitive constitutional settlement. Instead, the ruling intensified conflict by widening the gulf between Northern and Southern interpretations of federal power, citizenship, and the future of slavery in the national territories.

Scott’s Claim and the Legal Path to the Supreme Court

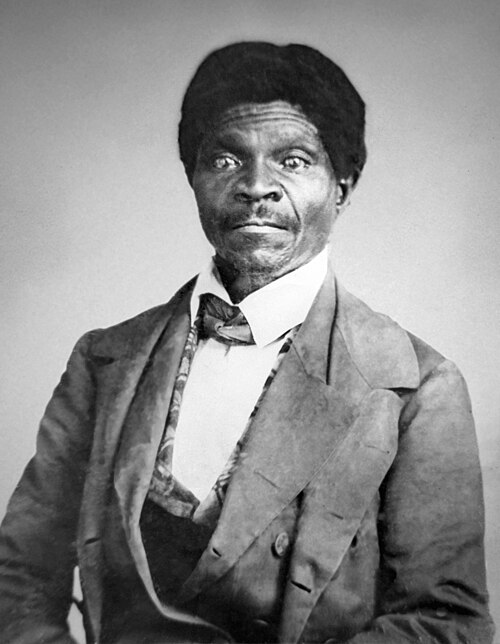

Enslaved man Dred Scott sued for his freedom on the grounds that extended residence in free territory made him legally free.

This photograph shows Dred Scott, the enslaved man whose freedom suit became the basis of the landmark 1857 Supreme Court decision. His case raised significant questions about citizenship, federal authority, and slavery in free territories. The image emphasizes that the constitutional crisis centered on the lived experiences of an individual rather than abstract legal theory. Source.

Popular Sovereignty: The principle that settlers in a U.S. territory should decide whether slavery would be permitted.

His case moved through multiple state and federal courts, reflecting how slavery questions increasingly demanded clarification from the highest constitutional authority. The Supreme Court’s willingness to hear the case showed how deeply national leaders hoped legal rulings could prevent further political collapse.

Taney’s Majority Opinion: Defining Citizenship and Limiting Federal Power

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered an expansive majority opinion that reinterpreted the Constitution in ways that profoundly shaped sectional debate. His argument addressed citizenship, the status of enslaved people, and federal authority over the territories.

Citizenship and Constitutional Personhood

Taney declared that no person of African descent—enslaved or free—could be a citizen of the United States.

Citizenship (Antebellum Legal Meaning): Membership in the national political community that conferred rights such as suing in federal court.

This sweeping statement contradicted state laws recognizing free African Americans as citizens and stripped them of claims to national legal protection.

Enslaved People as Property

Taney argued that enslaved people were property, protected by the Fifth Amendment. By placing slaveholders’ property rights above federal or territorial regulation, the ruling nationalized a pro-slavery interpretation of the Constitution. This interpretation directly threatened Northern states and territories that sought to limit slavery’s advance.

The Missouri Compromise Declared Unconstitutional

The Court struck down the Missouri Compromise of 1820, ruling that Congress lacked constitutional authority to ban slavery in any U.S. territory.

This map illustrates the Missouri Compromise of 1820, marking free states, slave states, and the dividing line at 36°30′. It clarifies the geographic boundaries Congress attempted to impose on the expansion of slavery, which the Dred Scott decision later declared unconstitutional. Additional territorial labels and state names appear but serve to orient the viewer within the broader national landscape. Source.

Because Congress had long exercised power over territorial legislation, this declaration represented a dramatic redefinition of federal authority. According to Taney, territorial legislatures were similarly barred from prohibiting slavery, effectively forcing all U.S. territories to remain legally open to slaveholding.

The Limits of Federal Solutions

Although intended to settle slavery in the territories once and for all, the ruling demonstrated how federal judicial action could actually exacerbate sectional divisions.

Northern Reactions: Rejecting the Court’s Legitimacy

Northerners responded with outrage. Many viewed the decision as evidence of a Slave Power conspiracy—the belief that pro-slavery interests controlled national institutions.

Slave Power: A Northern term describing the perceived political dominance of Southern slaveholders over federal institutions.

Republicans, whose platform was built on preventing the expansion of slavery, rejected the Court’s authority on territorial slavery questions. Northern newspapers, ministers, and politicians framed the ruling as an attack on free-labor ideology and on the rights of states and territories to restrict slavery.

After this rejection, the judicial attempt to impose a uniform national policy became unenforceable in large sections of the country.

Southern Reactions: Validation of Constitutional Pro-Slavery Arguments

Southerners, by contrast, celebrated the ruling as a long-awaited constitutional vindication. Taney’s reasoning aligned with strict constructionist and states’ rights arguments that portrayed slavery as protected by the nation’s founding document. Many Southern leaders now believed that territorial slavery was constitutionally secure and that any federal restriction—legislative or executive—was illegitimate.

Political Consequences and Escalating Conflict

The decision’s impact extended beyond legal doctrine, influencing political alignments and undermining attempts at compromise.

Weakening of National Compromise Efforts

Because the ruling nullified a long-standing legislative compromise and rejected congressional authority to regulate slavery in the territories, it weakened the federal government’s ability to manage sectional disputes. Leaders who had attempted compromise through legislation or judicial resolution found themselves without viable tools to contain the crisis.

Strengthening the Republican Party

The decision energized the Republican Party, which framed resistance to its implications as a defense of both free labor and democratic self-government. Republican leaders—most notably Abraham Lincoln—argued that the ruling threatened not only political liberty but the Founders’ vision of limiting slavery’s growth. The widening divide over whether to accept or resist the ruling rapidly polarized national politics.

Increasing the Probability of Secession

By 1860, the Dred Scott decision had helped solidify irreconcilable constitutional visions between North and South. Southerners insisted the ruling must be enforced; Northerners refused. This breakdown in shared constitutional interpretation contributed directly to the crisis that followed Lincoln’s election and made federal compromise increasingly impossible.

The Lasting Significance for Sectional Conflict

The Dred Scott decision exemplified the limits of federal solutions when national institutions were themselves polarized. Instead of grounding national unity in constitutional interpretation, the ruling exposed the inability of the Supreme Court to resolve territorial slavery. By invalidating legislative compromise and redefining constitutional citizenship, it accelerated the sectional breakdown that propelled the United States toward civil war.

FAQ

The Court aimed to settle multiple unresolved constitutional questions about slavery in one judgment, believing that a comprehensive ruling would stabilise the nation.

Taney and several justices sought to resolve:

• Whether African Americans could be citizens.

• Whether Congress had authority to regulate slavery in the territories.

• Whether territorial governments could prohibit slavery.

Their broad approach reflected the belief that only a sweeping constitutional interpretation could prevent further national conflict, though the opposite occurred.

The ruling prompted many Northerners to argue that the Court had exceeded its constitutional role, challenging the notion that judicial decisions were automatically binding on all political actors.

Some Northern legal scholars and politicians contended that:

• The Court had effectively rewritten the Constitution to support slavery.

• Citizens and legislators retained the right to resist rulings they believed violated republican principles.

This contributed to a growing belief that the Supreme Court could not serve as a neutral arbiter in sectional disputes.

Political parties interpreted the ruling through the lens of their sectional commitments, which amplified rather than tempered national divisions.

• Democrats generally accepted or supported the ruling, especially Southern factions who saw it as a confirmation of constitutional protections for slavery.

• Northern Democrats were more divided but often defended the Court to maintain party unity.

• Republicans uniformly rejected the ruling, using it to argue that the federal government had been captured by pro-slavery interests.

The decision therefore widened existing fractures within and between national parties.

Many Northern moderates had accepted the Missouri Compromise as a workable, long-term framework for containing slavery geographically.

The ruling alarmed them because:

• It removed a long-standing political boundary that had prevented the westward spread of slavery.

• It suggested that no federal compromise on slavery would be considered constitutional.

• It signalled that slaveholding interests might demand the right to bring enslaved people anywhere in the nation.

This pushed some moderates closer to Republican positions.

In practical terms, the ruling emboldened slaveholders and weakened the security of enslaved people seeking refuge in territories that had previously prohibited slavery.

• Slaveholders gained confidence that federal law would protect their claims in any territory.

• Enslaved people could no longer rely on territorial legal frameworks that had previously offered hope of freedom.

• Pro-slavery territorial governments felt affirmed in enforcing slave codes or resisting anti-slavery legislation.

The ruling did not expand slavery everywhere immediately, but it dramatically reduced legal barriers that had previously restricted its movement.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Dred Scott decision increased sectional tensions in the United States.

Question 1

1 mark

General statement identifying that the ruling heightened tensions between North and South.

2 marks

Clear explanation of a specific reason, such as the North’s rejection of the ruling or the South’s celebration of it, showing polarisation.

3 marks

Well-developed explanation demonstrating how the decision directly escalated sectional conflict, for example by invalidating the Missouri Compromise or by suggesting Congress lacked the power to restrict slavery.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford demonstrated the limits of federal authority in resolving the issue of slavery in the territories.

Question 2

4 marks

Basic analysis explaining that the ruling attempted to settle the slavery issue but failed, touching on at least one limit of federal solutions (e.g., lack of national acceptance).

5 marks

More detailed analysis referencing both Northern and Southern reactions or discussing how the ruling undermined political compromise and congressional authority.

6 marks

Sustained, well-argued analysis demonstrating deep understanding of the ruling’s constitutional reasoning, its reception across sections, and how it exposed the federal government’s inability to impose a unifying policy on territorial slavery.