AP Syllabus focus:

‘As party loyalties weakened, sectional parties emerged—most notably the Republican Party in the North.’

As national political loyalties fractured in the 1850s, worsening sectional tensions produced new political alignments, enabling the emergence of the Republican Party as a dominant Northern force.

The Breakdown of National Parties in the 1850s

The rise of the Republican Party must be understood against the collapse of the Second Party System, long dominated by the Whigs and Democrats. Growing disputes over slavery’s expansion, intensified by the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, destabilized long-standing coalitions. Politicians who once relied on broad national appeal increasingly found their bases fractured along sectional lines.

Declining Cross-Regional Party Unity

Both major national parties suffered when slavery expansion could no longer be managed through compromise legislation.

Northern and Southern wings of the Democratic Party diverged over whether the federal government should protect slavery in the territories.

The Whig Party disintegrated as antislavery Northern Whigs and proslavery Southern Whigs could no longer share a coherent platform.

Nativist movements, particularly the Know-Nothings, further disrupted traditional party loyalties, drawing voters away from older parties even if only temporarily.

This political fragmentation created a vacuum, especially in the North, in which a new sectional party could emerge.

Foundations of the Republican Party

The Republican Party developed as a coalition of groups united primarily by opposition to the expansion of slavery, though they differed on many other issues. It quickly formed the most successful sectional party in American history up to that point, drawing together diverse political traditions.

Composition of the Emerging Coalition

The party’s founders included:

Former Northern Whigs, displaced by their party’s collapse.

Free-Soilers, who opposed slavery’s expansion to preserve opportunities for free labor.

Anti-Nebraska Democrats, disillusioned by their party’s support of the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

Abolitionists, though the party itself initially stopped short of demanding immediate abolition.

Their shared political aim focused on stopping slavery’s territorial growth, not eliminating slavery where it already existed, which allowed the coalition to broaden support among moderate Northern voters.

Campaign banner for the 1856 Republican ticket of John C. Frémont and William L. Dayton, decorated with patriotic symbols. The design reflects early Republican efforts to craft a unified public identity. The banner visually reinforces the party’s emergence as a new sectional coalition. Source.

Sectional Party: A political party whose support is concentrated in one geographic region and whose platform reflects the interests and priorities of that region.

This coalition’s structure reflected broader sectional realignments across the nation.

Ideological Foundations: Free Labor, Republicanism, and Moral Opposition

Although not all Republicans were abolitionists, the party forged a powerful ideology emphasizing the superiority of free labor and the dangers of slavery’s expansion for Northern society. These ideas helped transform opposition to slavery from a moral concern into a core political principle.

The Free-Labor Vision

Republicans argued that slavery threatened the economic and social foundations of the North. Their free-labor ideology rested on several key claims:

Free labor promoted social mobility, allowing individuals to rise through hard work.

Slavery degraded labor, reducing incentives for innovation and obstructing opportunities for white workers.

Territorial expansion of slavery threatened to shut free labor out of new lands, foreclosing opportunities for independent landholding and enterprise.

Many Republicans believed the West should remain reserved for free white settlers, a view tied to both egalitarian and exclusionary assumptions. While this ideology contained racial limitations, it proved effective in drawing wide support among white Northern voters.

Political Strategy and Party Organization

The Republican Party’s rapid rise was also the result of effective political organization and strategic framing.

Building a Broad Northern Base

Republicans capitalized on public outrage over the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which had overturned the Missouri Compromise’s restriction on slavery’s expansion. Their messaging emphasized:

Moral concerns, portraying slaveholders as a powerful “Slave Power” conspiracy threatening republican liberty.

Economic arguments, claiming slavery distorted markets and harmed white workers.

Constitutional reasoning, asserting that Congress had full authority to restrict slavery in the territories.

By blending these appeals, Republicans created a message that resonated across class lines in the North.

The Role of Political Innovation

Republicans pioneered modern campaigning techniques, including:

Coordinated state and local party committees

Well-developed partisan newspapers

Large-scale rallies and political pamphlets

These organizational innovations strengthened party cohesion and helped unify diverse factions.

From Sectional Movement to National Influence

By the late 1850s, the Republican Party had become the dominant political force in the North. Their growing political success reshaped national politics.

Electoral Growth and the Road to 1860

Republican electoral success illustrated the deepening sectional divide:

In many Northern states, Republicans quickly replaced the Whigs as the principal alternative to the Democrats.

The party’s strong showing in the 1856 presidential election, though not victorious, demonstrated its viability as a major political force.

As sectional tensions escalated, Southern voters rejected the possibility of supporting a party dedicated to halting slavery’s expansion.

Republicans remained almost entirely a Northern party, but within that region they surged toward majority status.

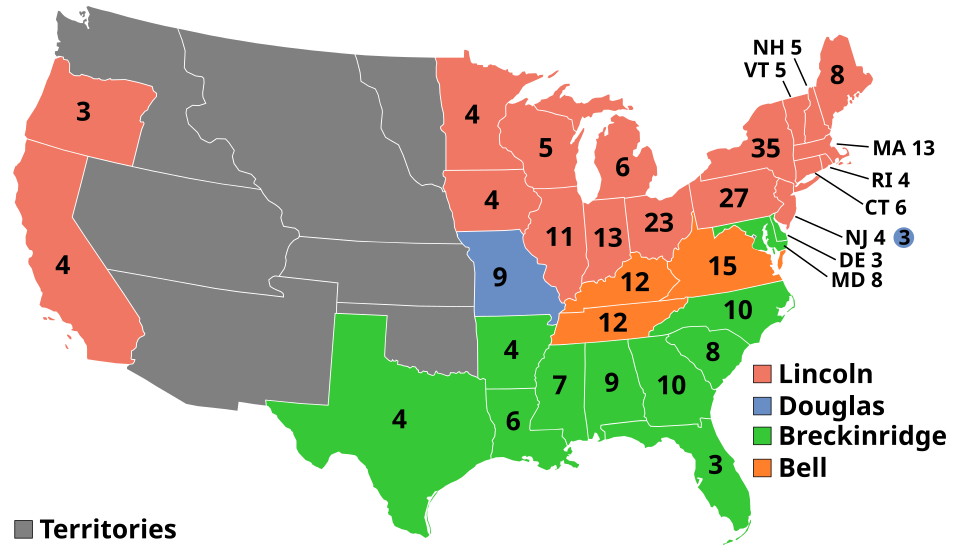

Map of the 1860 presidential election results, highlighting Lincoln’s electoral dominance in the North and West. The distribution of state colors visually demonstrates the sectional nature of Republican support. The image includes detailed vote information that goes beyond the syllabus but reinforces the regional political divide. Source.

Foreshadowing National Crisis

The rise of a powerful sectional party deepened national polarization. For many white Southerners, a Republican victory was unacceptable, as it signaled a government controlled by a region hostile to slavery’s future. This fear would become central to secessionist arguments after Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, when the Republican ascendancy directly contributed to the unraveling of the Union.

Legacy Within the Sectional Crisis

By emerging as the most influential sectional party of the era, the Republican Party fundamentally reshaped the nation’s political landscape. Its commitment to stopping slavery’s expansion positioned it at the center of the debates that propelled the United States toward civil war and ultimately transformed its political order.

FAQ

The Republicans prioritised stopping the expansion of slavery, framing it as the central political and moral issue threatening national liberty.

In contrast, the Know-Nothings focused on anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic policies. While some early Republicans had nativist leanings, the party chose to emphasise slavery-related issues to build a broader Northern coalition, enabling it to attract former Whigs, Free-Soilers, and disaffected Democrats who disagreed on immigration but united in opposing slavery’s growth.

Republican organisers used a rapidly expanding network of Northern newspapers to promote anti-slavery expansion rhetoric and counter Southern pro-slavery publications.

Editors often published political cartoons, reprinted speeches, and circulated ideological arguments connecting the Slave Power to threats against free labour.

This print culture created a shared political language across the North, helping unify supporters across states and reinforcing the party’s sectional identity.

Republicans adopted new forms of political outreach:

Highly coordinated county and state party committees

Mass rallies that framed political participation as civic duty

Distribution of pamphlets written in accessible language

These strategies energised voters who felt alienated from traditional party politics, especially young men in urban areas and settlers in expanding Western states.

Southern leaders believed Republican success would erode their long-standing influence in national institutions.

They feared that halting slavery’s expansion would ultimately weaken slavery where it already existed by limiting economic growth, political leverage, and representation in Congress.

Moreover, Republican critiques of the Slave Power were interpreted as direct attacks on Southern honour and social order, intensifying their sense of vulnerability.

The coalition included moderate anti-slavery expansionists, Free-Soilers focused on white labour, and more radical abolitionists.

Internal debates often centred on whether the party should stress moral condemnation of slavery or focus on economic arguments about free labour.

This diversity helped widen the party’s appeal but also required careful compromise in platform writing to avoid alienating key groups within the Northern electorate.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Explain one reason why the Republican Party emerged as a sectional political party in the 1850s.

Mark scheme:

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., collapse of the Whig Party, reaction to the Kansas–Nebraska Act).

2 marks: Provides a basic explanation linking the reason to opposition to slavery’s expansion or growing sectional tensions.

3 marks: Gives a well-developed explanation showing how that reason specifically encouraged the Republican Party to form as a Northern, anti-slavery-expansion party.

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Analyse the extent to which the rise of the Republican Party contributed to increasing sectional tension in the United States during the 1850s.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks: Identifies relevant points (e.g., Republican opposition to slavery expansion, Southern fears of a Northern-dominated government).

3–4 marks: Develops these points with clear explanation of how Republican electoral growth, ideological positions, or political strategies heightened sectional division.

5–6 marks: Provides a fully analytical answer that clearly links Republican Party rise to national polarisation while also considering other contributing factors (e.g., the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Democratic Party divisions), showing a nuanced understanding of its relative importance.