AP Syllabus focus:

‘National leaders attempted to resolve slavery in the territories through measures like the Kansas–Nebraska Act, but these efforts failed to reduce conflict.’

The Kansas–Nebraska Act shattered previous compromises on territorial slavery, intensifying sectional rivalry, destabilizing national politics, and accelerating the nation’s march toward open conflict and civil war.

The Breakdown of Earlier Territorial Compromises

The Kansas–Nebraska Act emerged in 1854 as a direct challenge to the Missouri Compromise, the long-standing agreement that had prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ line in the Louisiana Territory. The Missouri Compromise had provided a workable—though imperfect—framework for limiting slavery’s expansion.

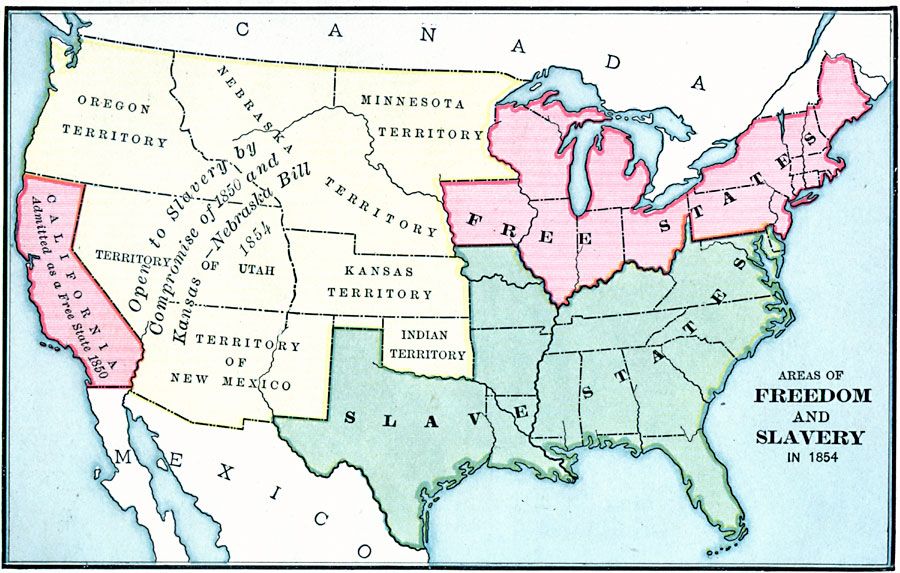

This map illustrates the political geography of the United States in 1854, distinguishing free states, slave states, and territories opened to slavery after earlier compromises. Kansas and Nebraska are clearly labeled, situating the territorial debates triggered by the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Additional territorial labels extend beyond this subsubtopic but help contextualize the region within the broader continental landscape. Source.

The Push for a Northern Transcontinental Railroad

Senator Stephen A. Douglas, a key architect of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, sought federal approval for a northern transcontinental railroad. To secure Southern support, Douglas needed to structure the remaining Louisiana Purchase territories—Kansas and Nebraska—in ways favorable to pro-slavery interests. The political bargaining surrounding infrastructure thus became intertwined with the intensifying national debate over slavery.

Popular Sovereignty and Its Political Calculations

Douglas’s proposed solution was popular sovereignty, the idea that settlers in a territory should vote to determine whether slavery would exist there.

Popular Sovereignty: A doctrine asserting that residents of a territory, rather than Congress, should decide the status of slavery within that territory.

By framing the policy as democratic self-determination, Douglas hoped to ease sectional tensions. Instead, popular sovereignty destabilized the political landscape.

Why Popular Sovereignty Undermined Stability

Popular sovereignty appeared neutral, but in practice it nullified the Missouri Compromise and opened regions previously closed to slavery. This shift ignited immediate controversy:

Northern free-soilers condemned the proposal as capitulation to the “Slave Power.”

Southern pro-slavery leaders welcomed the possibility of expanding slavery into areas once barred.

Moderate politicians feared the loss of a clear national standard, predicting intensified disputes.

The act set the stage for aggressive migration into the new territories as groups sought to control the outcome of local votes.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854

The legislation created two new territories—Kansas and Nebraska—and declared that the question of slavery would be decided by popular sovereignty. Its passage required support from both Northern and Southern Democrats, but it sharply divided the Democratic Party and devastated Whig unity.

The Immediate Political Effects

The act’s consequences for national politics were dramatic:

It ended the viability of the Whig Party, already weakened by internal divisions over slavery.

It deepened fractures within the Democratic Party, particularly in the North.

It contributed directly to the rise of sectional political parties, which would soon coalesce into the Republican Party.

These cascading effects mirrored the AP syllabus emphasis that national leaders’ attempts to settle territorial slavery “failed to reduce conflict.”

Bleeding Kansas: Violence as a Consequence of Legislative Failure

The most visible sign of the act’s failure appeared in Kansas itself. Competing pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers rushed into the region to influence elections, leading to a period of widespread violence known as Bleeding Kansas.

This 1856 cartoon depicts Northern fears that the Kansas–Nebraska Act enabled pro-slavery leaders to impose slavery on free territories. Political figures such as Pierce, Douglas, and Buchanan appear forcing a bound freesoiler onto the “Democratic Platform” labeled with “Kansas.” The cartoon also contains extra references to expansionist aims such as “Cuba” and “Central America,” which extend beyond this subsubtopic but help illustrate the broader anxieties of the era. Source.

Conditions That Fostered Conflict

The collapse of a clear territorial standard created:

Competing legislatures, each claiming legitimacy

Election fraud, including organized efforts by pro-slavery “Border Ruffians” from Missouri

Militant abolitionist resistance, including armed groups determined to protect free-soil settlements

The territory effectively became a battleground, and national newspapers publicized brutality on both sides.

National Reactions to Kansas Violence

Bleeding Kansas convinced many Northerners that the Slave Power sought expansion at any cost, while Southerners grew increasingly suspicious of what they viewed as violent Northern abolitionism. This mutual distrust contributed to the unraveling of national political cooperation.

Collapse of Territorial Compromise and Intensifying Sectionalism

With the Kansas–Nebraska Act, Congress abandoned a concrete, long-standing territorial standard. This not only revived debates once presumed settled but also proved that legislative compromise could no longer contain sectional animosity.

Key Factors in the Collapse

The repeal of the Missouri Compromise signaled a break with past national agreements.

Popular sovereignty invited conflict rather than resolving it, as competing factions attempted to manipulate territorial outcomes.

National leaders proved unable to enforce stability, undermining public faith in congressional problem-solving.

Broader Implications for the Union

The act illustrated how deeply sectional the nation had become by the 1850s. Instead of smoothing tensions, it:

Encouraged radicalization in both regions

Accelerated the formation of new political coalitions

Created territorial flashpoints that exposed national weakness

The Kansas–Nebraska Act demonstrated that legislative power struggles could not override the profound moral, economic, and political differences dividing North and South.

FAQ

Douglas assumed that removing Congress from slavery decisions would neutralise sectional arguments. He believed that local settlers, not national politicians, were best placed to determine their own institutions.

He also hoped that popular sovereignty would broaden support for westward expansion by making territorial organisation appear more democratic.

Finally, Douglas calculated that decentralising the slavery question would preserve the Democratic Party’s national coalition, although this proved incorrect.

Settlers engaged in organised political activity intended to tip the balance in favour of their faction.

Methods included:

• Forming emigrant aid societies to encourage mass migration of like-minded settlers

• Establishing armed vigilance groups to defend polling sites

• Creating parallel territorial governments claiming legality

• Publishing political newspapers to sway new arrivals and discredit rivals

These activities reflected the weakness of federal oversight and the high stakes attached to territorial status.

The federal government struggled to enforce consistent authority in Kansas, creating opportunities for factional control.

Presidents Pierce and Buchanan appointed pro-slavery territorial officials, which undermined confidence among free-soil settlers.

Federal troops were occasionally deployed but mainly to prevent open warfare rather than resolve political legitimacy disputes, leaving fundamental questions unanswered.

This vacuum of enforcement encouraged further fraud, legislative duplication and violent intimidation.

Newspapers framed Kansas as a symbolic struggle for the future of the Union.

Northern papers reported Border Ruffian raids, fraudulent elections and attacks on free-soil communities as proof of a Slave Power conspiracy.

Southern papers emphasised abolitionist militancy and portrayed free-soil settlers as violent radicals threatening property rights.

The highly partisan coverage intensified mutual suspicion, turning a territorial dispute into a national ideological conflict.

The Act destroyed the credibility of previous compromises, convincing many Northerners that only a new party could prevent slavery’s expansion.

Former Whigs, Free Soilers and anti-Nebraska Democrats united around opposition to the Act’s repeal of the Missouri Compromise.

The party’s early growth was strongest in regions where outrage over Bleeding Kansas was most pronounced, giving the Republicans both moral urgency and electoral momentum.

This realignment made politics increasingly sectional in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Kansas–Nebraska Act contributed to increasing sectional tensions in the 1850s.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid impact (e.g., repeal of the Missouri Compromise; rise of sectional parties; outbreak of violence).

1 mark for explaining how the Kansas–Nebraska Act directly caused that impact (e.g., popular sovereignty opening new territories to slavery).

1 mark for linking this impact to growing sectional tension (e.g., Northern outrage, Southern hopes of expansion, collapse of national political cooperation).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which the Kansas–Nebraska Act was responsible for the collapse of national political compromise in the decade before the Civil War.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for establishing a clear argument or line of reasoning (e.g., that the Act was highly significant, partly significant, or less significant).

1 mark for explaining how the Act undermined earlier compromises (e.g., repealing the Missouri Compromise; introducing popular sovereignty).

1 mark for describing political consequences (e.g., disintegration of the Whig Party; deepening Democratic divisions; rise of the Republican Party).

1 mark for describing social or territorial consequences (e.g., Bleeding Kansas, publicised violence, national polarisation).

1 mark for considering an additional factor beyond the Kansas–Nebraska Act (e.g., abolitionist activism, pro-slavery expansion, economic differences).

1 mark for a reasoned judgement on the relative importance of the Act in the breakdown of political compromise.