AP Syllabus focus:

‘Technological advances, large-scale production methods, and new markets fueled the rise of industrial capitalism in the United States.’

In the decades after the Civil War, the United States experienced dramatic industrial expansion driven by transformative technologies, reorganized production, and rapidly widening national and international markets.

Big-Picture Causes of Post–Civil War Industrial Capitalism

Industrial capitalism grew rapidly after 1865 because several long-term forces converged to reshape the economy. These forces operated together, linking innovation, investment, and geography into a national industrial system.

Technological Advances as a Catalyst

New industrial technologies accelerated production, lowered costs, and expanded the scale of business operations. Inventions such as improved steelmaking processes, advanced machinery, and communications technologies reshaped how firms operated.

Technological innovation: The development and application of new tools, processes, or systems that increase efficiency, reduce costs, or create new economic opportunities.

Telegraph networks and, later, telephone systems integrated distant regions into unified commercial zones. These communication systems enabled businesses to coordinate production, shipping, and pricing quickly across vast distances. As the country became more physically connected through railroads and telegraph lines, producers gained access to millions of potential customers.

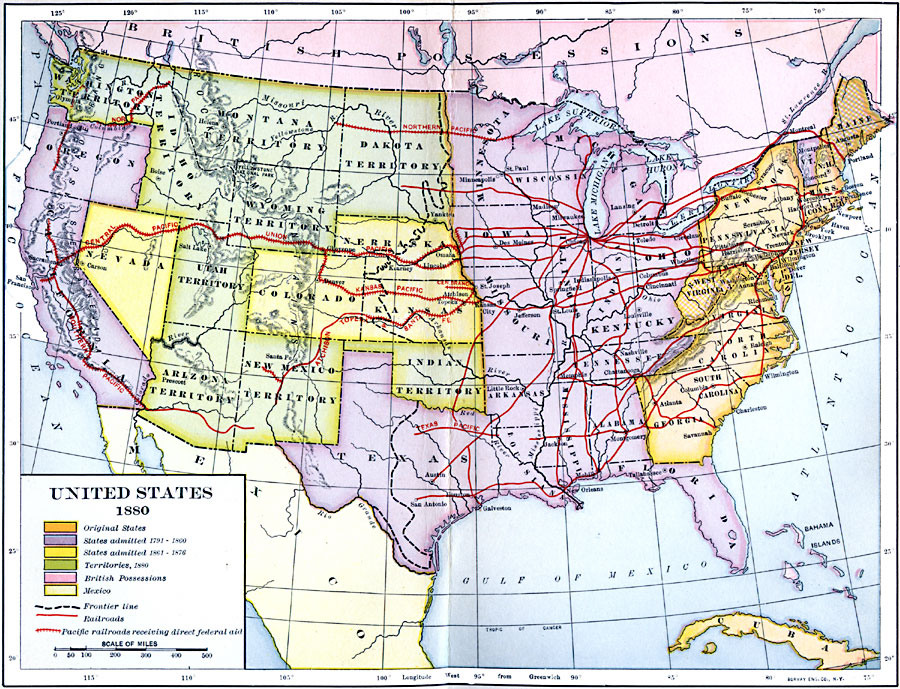

Map of United States Expansion and the Railroads, 1880, showing how expanding rail networks linked distant regions into a single national market. Additional geographic and territorial details extend beyond this subsubtopic but help contextualize the growth of industrial capitalism. Source.

Growing urban populations increased demand for mass-produced goods, while improved transportation allowed Western raw materials—such as coal, timber, and minerals—to reach Eastern factories quickly.

International markets also grew in importance. European demand for American agricultural and industrial products encouraged U.S. firms to scale production. Foreign investment flowed into American railroads and industry, accelerating economic growth and enabling the construction of the infrastructure on which national markets depended.

Large-Scale Production and the Rise of the Modern Factory

The shift toward large-scale production methods represented a defining feature of postwar industrial capitalism. Mechanized factories reorganized labor and capital in ways that dramatically increased output.

Key elements of large-scale production included:

Mechanization, which replaced or supplemented skilled labor with machines capable of continuous, standardized work.

Division of labor, breaking tasks into smaller steps, allowing unskilled or semi-skilled workers to perform specialized roles.

Capital-intensive facilities, requiring large upfront investments but producing far greater quantities of goods at lower per-unit costs.

Together, these changes created economies of scale, allowing businesses to compete effectively in expanding markets and undercut smaller producers.

National and International Markets Expand

The emergence of new national markets played a central role in fueling industrial capitalism. Railroad technology, particularly standard-gauge tracks and more powerful locomotives, ensured that goods could be moved efficiently nationwide, reinforcing the rise of a connected industrial economy.

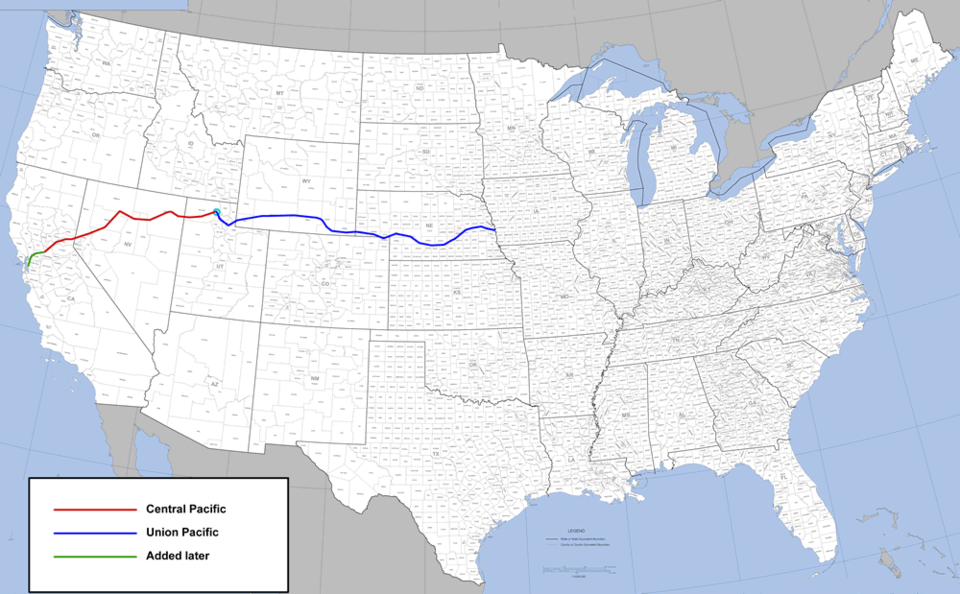

Map of the route of the first American transcontinental railroad from Omaha to Sacramento, illustrating how one continuous rail corridor connected distant regions. Its focus on a single route—rather than the full network—provides a clean view of a pivotal infrastructural achievement of industrial capitalism. Source.

As the country became more physically connected through railroads and telegraph lines, producers gained access to millions of potential customers. Growing urban populations increased demand for mass-produced goods, while improved transportation allowed Western raw materials—such as coal, timber, and minerals—to reach Eastern factories quickly.

International markets also grew in importance. European demand for American agricultural and industrial products encouraged U.S. firms to scale production. Foreign investment flowed into American railroads and industry, accelerating economic growth and enabling the construction of the infrastructure on which national markets depended.

Interconnected Systems of Production and Distribution

Industrial capitalism relied on networks that linked raw materials, production centers, and consumers. Several layers of this system emerged after the Civil War:

Resource extraction in the West supplied fuels and materials to industrial centers.

Railroad companies operated as both transportation systems and powerful business entities controlling access to markets.

Urban manufacturing hubs in the Northeast and Midwest housed enormous factories that produced steel, textiles, machinery, and consumer goods.

Commercial distributors and wholesalers moved manufactured goods into stores across the nation, standardizing retail experiences.

By integrating production and distribution, businesses could control costs more effectively and reduce dependence on local suppliers.

Capital Investment and Industrial Growth

Industrial capitalism after 1865 also depended on vast capital investment, particularly in railroads, factories, and heavy machinery. Investors and banks channeled money into enterprises promising high returns. The expansion of national capital markets enabled corporations to sell stocks and bonds to finance large operations.

Capital: Financial resources—such as money or assets—used to fund investment in production, infrastructure, or business expansion.

These financial tools allowed companies to grow far beyond what individual owners could fund. Firms could purchase advanced machinery, acquire competitors, and expand into new regions, reinforcing industrial consolidation.

Following this, investment supported continuous technological improvement, since firms with greater financial resources could adopt innovations faster, further widening the gap between large corporations and smaller businesses.

Labor Supply and Industrial Workforce Expansion

A growing and diverse labor force provided essential support for industrial capitalism. Immigration from Europe, internal migration from rural America, and the movement of formerly enslaved people into wage labor created a vast pool of workers willing to take industrial jobs.

This expanding workforce enabled factories to operate at large scale, while competitive labor markets kept wages relatively low—further reducing production costs.

Government Support and Economic Policy

Although not detailed extensively in the specification excerpt, pro-growth government policies indirectly supported the rise of industrial capitalism by encouraging infrastructure development and protecting business interests.

Policies included:

Protectionist tariffs promoting domestic manufacturing.

Subsidies and land grants aiding railroad construction.

Limited regulatory oversight, allowing corporations to expand with few constraints.

These conditions strengthened the environment in which technology, large-scale production, and new markets could interact to fuel industrial capitalism.

The Feedback Loop of Industrial Expansion

Once underway, industrial growth became self-reinforcing. New technologies increased production; larger markets demanded more goods; expanding factories required more labor and capital; and all these forces encouraged further innovation. The result was a dynamic, interconnected economic system that transformed the United States into a major industrial power by the late nineteenth century.

FAQ

Patent registrations surged after 1865, giving inventors legal protection and encouraging investment in new machinery and production systems.

This environment rewarded innovation by allowing inventors and firms to commercialise technologies without immediate imitation.

• Companies could plan large-scale production knowing their processes were temporarily protected.

• Investors were more willing to fund risky ventures because patents reduced competitive uncertainty.

Patent culture also fostered collaboration between engineers, entrepreneurs, and financiers, helping inventions move quickly from workshop prototypes to industrial application.

Rapid communication allowed businesses to coordinate supply chains across long distances, reducing delays and inefficiencies.

Telegraph lines enabled real-time updates on prices, shipping schedules, and inventory, allowing firms to plan production more accurately.

• Railroads depended on telegraphs to manage traffic and safety.

• Factories relied on quick information flow to synchronise material deliveries and distribution.

Together, these networks created a national commercial rhythm in which business decisions could be made at unprecedented speed.

As factories grew, owners could no longer oversee daily operations, leading to the rise of specialised managers.

These managers developed systems for tracking costs, supervising labour, and standardising production.

• Accounting methods became more sophisticated to handle vast inventories.

• Supervisory hierarchies ensured consistent output across large workforces.

Managerial skills became a competitive advantage, helping firms reduce waste and improve productivity within complex manufacturing environments.

Rural and urban areas became economically interdependent as industrial capitalism linked them through supply chains.

Cities relied on the countryside for raw materials such as grain, lumber, and minerals. Rural areas, in turn:

• Depended on cities for manufactured goods

• Accessed credit from urban banks

• Sold produce in distant markets rather than only locally

This reduced regional isolation and created a more integrated national economy with shared vulnerabilities to price swings and transportation disruptions.

Large-scale production required expensive machinery, extensive factory space, and steady supplies of raw materials—costs too high for most small producers.

Firms with greater capital could:

• Invest early in labour-saving technologies

• Withstand short-term losses during downturns

• Expand into multiple regions and secure wider markets

This financial advantage accelerated consolidation, as better-funded corporations outcompeted or absorbed smaller rivals, reinforcing the dominance of industrial capitalism.

Practice Questions

Explain one way in which technological advances contributed to the rise of industrial capitalism in the United States after the Civil War. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

Gives a basic description of a technological development (e.g., railroads, telegraph, mechanised factory equipment) with minimal or unclear linkage to industrial growth.

2 marks:

Explains a technological advance and provides a clear link to increased production, expanded markets, or business efficiency.

3 marks:

Offers a well-developed explanation showing how a specific technological innovation directly accelerated industrial capitalism, such as by lowering costs, integrating markets, enabling large-scale production, or improving communication and coordination.

Analyse the extent to which the expansion of national markets transformed patterns of production and distribution in the United States between 1865 and 1898. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

Identifies ways national markets expanded after 1865 and provides some explanation of how these changes influenced production or distribution.

May be descriptive rather than analytical, with limited discussion of extent.

5 marks:

Provides a clear analysis of how wider national markets reshaped production and distribution patterns, such as through large-scale factories, standardised goods, or expanded transport networks.

Shows an emerging judgement regarding the extent of transformation.

6 marks:

Presents a sustained and well-supported analysis demonstrating how expanded national markets fundamentally altered economic structures.

Integrates specific examples such as railroads connecting regions, increased availability of raw materials, urban growth driving demand, or factory reorganisation for mass production.

Makes a clear evaluative claim about the extent of change, supported by evidence.