AP Syllabus focus:

‘New systems of production and transportation consolidated agriculture; instability and market pressures encouraged farmers to organize and respond in different ways.’

Late nineteenth-century American farming became increasingly commercialized as new technologies and transportation networks reshaped production, tied farmers to national markets, and prompted organized responses to growing economic pressures.

The Transformation of Agricultural Production

New production systems created a more commercial, market-oriented agriculture in the post–Civil War period. As mechanization spread, farms shifted from subsistence patterns toward large-scale output intended for distant consumers. Farmers embraced innovations that enhanced efficiency but also deepened reliance on market fluctuations they could not control.

Mechanization and Rising Productivity

Technological advances—such as improved steel plows, mechanized reapers, and threshing machines—multiplied yields and encouraged specialization in cash crops. Greater output pushed farmers to participate fully in a national marketplace, linking their prosperity to broader economic conditions.

Specialization: The process by which farmers focus on producing a narrow range of crops for sale rather than a variety for home use.

Mechanization altered the rhythm of agricultural work, reduced labor needs, and raised expectations for productivity. However, it also required capital investment, often financed through credit, making farmers vulnerable to debt cycles and interest-rate shifts.

New reapers, binders, and eventually combine harvesters allowed a single farm family to cultivate and harvest far more acreage than before.

This photograph shows a McCormick reaper, a 19th-century harvesting machine that dramatically increased the amount of grain a single farm family could cut. By replacing hand-cutting with a horse-drawn mechanical system, the reaper helped push Midwestern farms toward large-scale commercial production. Although displayed in a modern setting, the machine closely resembles the design used during the agricultural expansion of the Gilded Age. Source.

Commercial Farming and Market Dependence

As agricultural goods flowed into national and international markets, competition intensified. Larger yields depressed prices, reducing farm incomes even as production increased. This paradox—overproduction lowering prices—became a defining feature of Gilded Age agriculture. Farmers now operated within a system where global supply, railroad freight rates, and distant market conditions shaped their daily livelihoods.

Transportation Networks and Integration into a National Market

Transportation innovations drew farmers into a rapidly expanding national economy. Railroads, in particular, revolutionized commercial agriculture by linking remote rural regions with urban processing centers and faraway consumers.

Railroad Expansion and Freight Rates

Railroads provided critical access to markets but also wielded disproportionate economic power. Their control over freight rates, storage, and shipping schedules placed farmers in a dependent position. Many railroads adopted discriminatory pricing, charging small farmers more per mile than large shippers, which sharpened rural resentment.

Discriminatory pricing: A practice in which railroads charged different customers unequal rates for similar services, often privileging large corporations over individual farmers.

Despite frustrations, railroads remained indispensable. Time-sensitive farm goods required rapid, reliable transport, and no alternative system offered comparable access. Freight networks also encouraged settlement, creating new regional farming centers that deepened agricultural integration across states.

Grain Elevators, Middlemen, and Market Pressures

Beyond the railroads, farmers contended with grain-elevator operators and commodity buyers who influenced prices. Middlemen frequently set grading standards and purchasing terms that reduced farmers’ bargaining power. As a result, many producers felt squeezed between rising costs and declining profits.

Farmer Responses to Market Instability

Persistent market volatility—combined with structural disadvantages—motivated farmers to organize collectively. These movements sought to counterbalance the economic power of railroads, grain buyers, and lenders. Their responses shaped emerging political and cooperative traditions in rural America.

Cooperative Experiments and Local Action

Farmers experimented with cooperatives designed to pool resources, negotiate better prices, and bypass exploitative intermediaries. These efforts reflected a growing belief that individual farmers acting alone lacked leverage in an increasingly consolidated national economy.

Cooperative: A jointly owned enterprise through which farmers shared costs, marketed goods collectively, or purchased supplies in bulk to secure better terms.

Cooperatives attempted to reduce expenses for equipment and storage, and some even launched cooperative grain elevators or retail stores. While results varied, the movement demonstrated farmers’ commitment to mutual aid in confronting structural disadvantages.

The Grange and the Power of Community

The Grange (Patrons of Husbandry) emerged as an influential organization blending social support with economic activism. It encouraged educational programming, promoted moral uplift, and called for cooperative enterprise. Grangers lobbied state governments to regulate railroad rates and grain-elevator fees, contributing to early regulatory laws known as Granger laws.

These laws aimed to curb the most abusive practices of transportation and storage companies. Though court challenges later weakened some measures, the movement established a precedent for state intervention in agricultural markets.

Alliances and Broader Political Mobilization

By the 1880s, farmers’ activism expanded into regional Farmers’ Alliances, which blended cooperative solutions with more ambitious political goals. Alliances advocated federal regulation of railroads, currency reform, and the creation of a subtreasury system to provide low-interest loans and crop storage. While this subsubtopic does not extend into later political developments, these organizing efforts reveal how instability and market pressures generated sustained collective action.

Agricultural Consolidation and the National Market

As new production and transportation systems reshaped rural life, farming became deeply embedded in a national economy characterized by consolidation. Larger farms often benefitted more from mechanization and long-distance shipping, increasing disparities within rural communities. Smaller farmers faced mounting costs and volatile prices, fueling demands for reform and solidarity.

Large grain elevators and terminal markets in cities like Chicago stored and blended grain from many local stations, turning it into standardized commodities that could be traded and shipped worldwide.

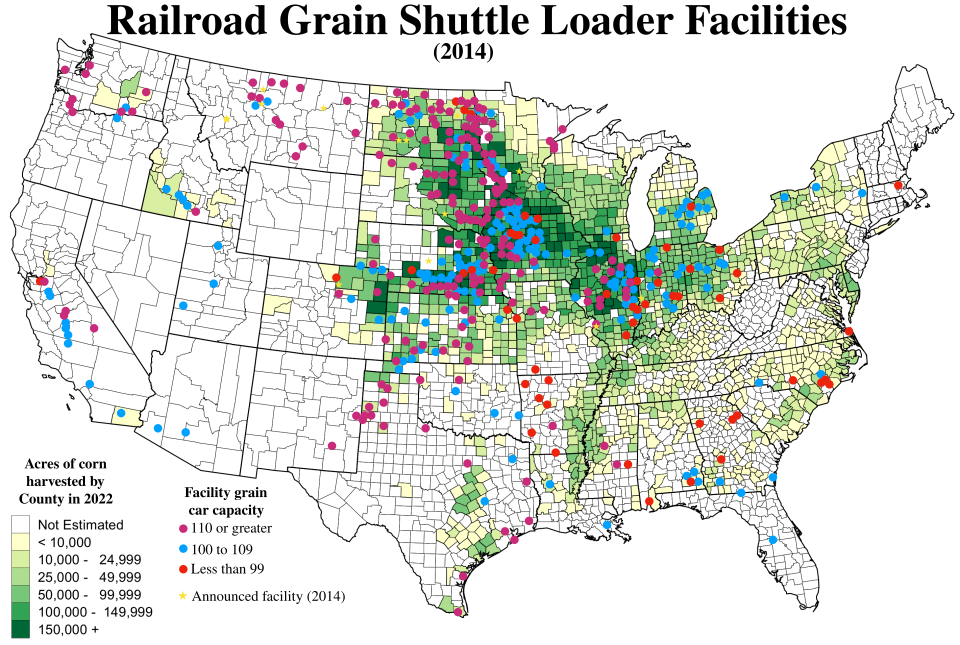

This schematic map shows the distribution of major U.S. grain shuttle loader facilities, which—like their 19th-century predecessors—link storage sites to rail lines for long-distance shipment. Although the facilities shown are modern, the diagram clearly illustrates how grain elevators and rail infrastructure together create a national marketing system. The map includes more locations than are required by the AP syllabus, but visually reinforces the integration of storage and transport in commercial agriculture. Source.

Many rural Americans recognized that the promise of technological innovation came with significant risks: dependence on powerful corporations, vulnerability to fluctuating markets, and erosion of local autonomy. Their organized responses reflected both the challenges and the adaptive resilience that defined agricultural life in the Gilded Age.

FAQ

Federal land policies such as the Homestead Act encouraged settlement across the Plains, creating vast new farming regions that quickly connected to rail lines.

This expansion increased the volume of grain entering national markets and strengthened the economic rationale for long-distance rail shipping and large terminal grain hubs.

Grain grading determined the price farmers received, since higher grades fetched premium rates in national exchanges.

Because grading was controlled by elevator operators and middlemen, farmers often believed standards were applied inconsistently, reducing their income.

This reinforced their desire for cooperative elevators and regulatory reforms.

Agricultural newspapers and magazines circulated technical advice, equipment reviews, and updates on national commodity prices.

They also helped farmers understand emerging economic trends, from freight pricing structures to market volatility, encouraging informed decision-making.

Some publications even promoted cooperative action and political reform, strengthening farmers’ shared identity.

Smaller farmers typically had less access to credit, fewer machines, and higher per-unit shipping costs.

They also lacked the bargaining power needed to negotiate favourable freight rates or storage fees.

Larger farms could absorb price swings more easily, reinforcing economic inequality within rural communities.

Harvest surpluses often coincided with peak shipping demand, enabling railroads and elevators to raise rates or limit access.

Farmers who could not store crops long-term had to sell immediately, usually at lower prices.

This seasonal vulnerability contributed to frustration and spurred efforts to create cooperative storage facilities.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which improved transportation systems affected farmers’ participation in national markets in the late nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for a general statement about transportation influencing market access.

2 marks for a clear explanation of how railroads or related systems enabled farmers to sell goods beyond local markets.

3 marks for a developed explanation showing the link between improved transportation and farmers’ increased dependence on national market prices, freight rates, or middlemen.

Acceptable points include:

Railroads allowed quicker shipment of crops to distant markets.

Access to national markets increased competition and tied farmers to fluctuating prices.

Freight rate structures could disadvantage farmers, increasing economic pressure.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which new systems of agricultural production and transportation contributed to farmer unrest and collective organisation between 1865 and 1898.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks for a basic analysis describing how new production or transport systems contributed to farmer unrest.

5 marks for analysis that explains both the economic pressures produced by mechanisation or transportation systems and the farmer responses.

6 marks for a well-developed analysis addressing multiple causes (mechanisation, price instability, discriminatory freight rates, grain elevator practices) and showing how these led to organised movements such as cooperatives, the Grange, or the Farmers’ Alliances.

Acceptable points include:

Mechanisation increased output but also debt burdens and dependence on market prices.

Overproduction contributed to declining crop prices and farmer hardship.

Railroads’ discriminatory freight rates limited farmers’ bargaining power.

Grain elevator operators and middlemen controlled grading and pricing, fuelling resentment.

These conditions stimulated cooperative action and the rise of organisations aiming to regulate railroads and achieve fairer market conditions.