AP Syllabus focus:

‘Financial panics and economic downturns shaped a variety of perspectives on the economy, wages, work, and the role of labor in industrial society.’

Industrial capitalism’s rapid expansion after the Civil War produced both immense opportunity and deep insecurity, prompting Americans to debate wages, labor rights, corporate power, and the causes of recurring financial crises.

Debating the Nature of Industrial Capitalism

Economic Volatility and the Problem of Financial Panics

During the late nineteenth century, the United States experienced repeated financial panics—rapid economic collapses fueled by factors such as overproduction, unstable banking systems, and speculation. These downturns severely affected workers, farmers, and small businesses, who often lacked savings or safety nets.

Financial Panic: A sudden economic crisis marked by collapsing credit markets, falling prices, and widespread business failures.

Financial panics in 1873 and 1893 intensified national debates over whether unregulated markets truly promoted long-term stability.

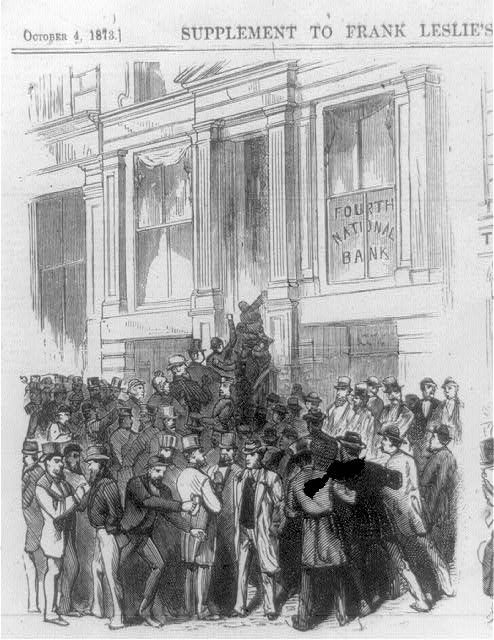

This engraving shows crowds rushing the Fourth National Bank in New York City during the Panic of 1873, illustrating how collapsing confidence triggered bank runs and intensified economic crises. The scene highlights the fragility of financial institutions during downturns. Although depicting one bank, it reflects broader national fears about unregulated capitalism’s instability. Source.

After panics subsided, tensions persisted because recovery typically favored large corporations, which could endure losses and consolidate competitors. Smaller firms and individual wage laborers remained vulnerable, reinforcing concerns that capitalism in its Gilded Age form disproportionately benefited the wealthy.

Perspectives on Wages, Work, and Inequality

Industrialization dramatically reshaped daily labor. Long hours, low wages, and dangerous conditions became common in factories, mines, and railroads. In this environment, differing viewpoints emerged about what constituted fair treatment and appropriate compensation.

Many workers argued that employers exploited economic insecurity to suppress wages, particularly during downturns when job scarcity heightened competition. Reformers emphasized the widening gap between wealthy industrialists—sometimes called robber barons—and ordinary laborers.

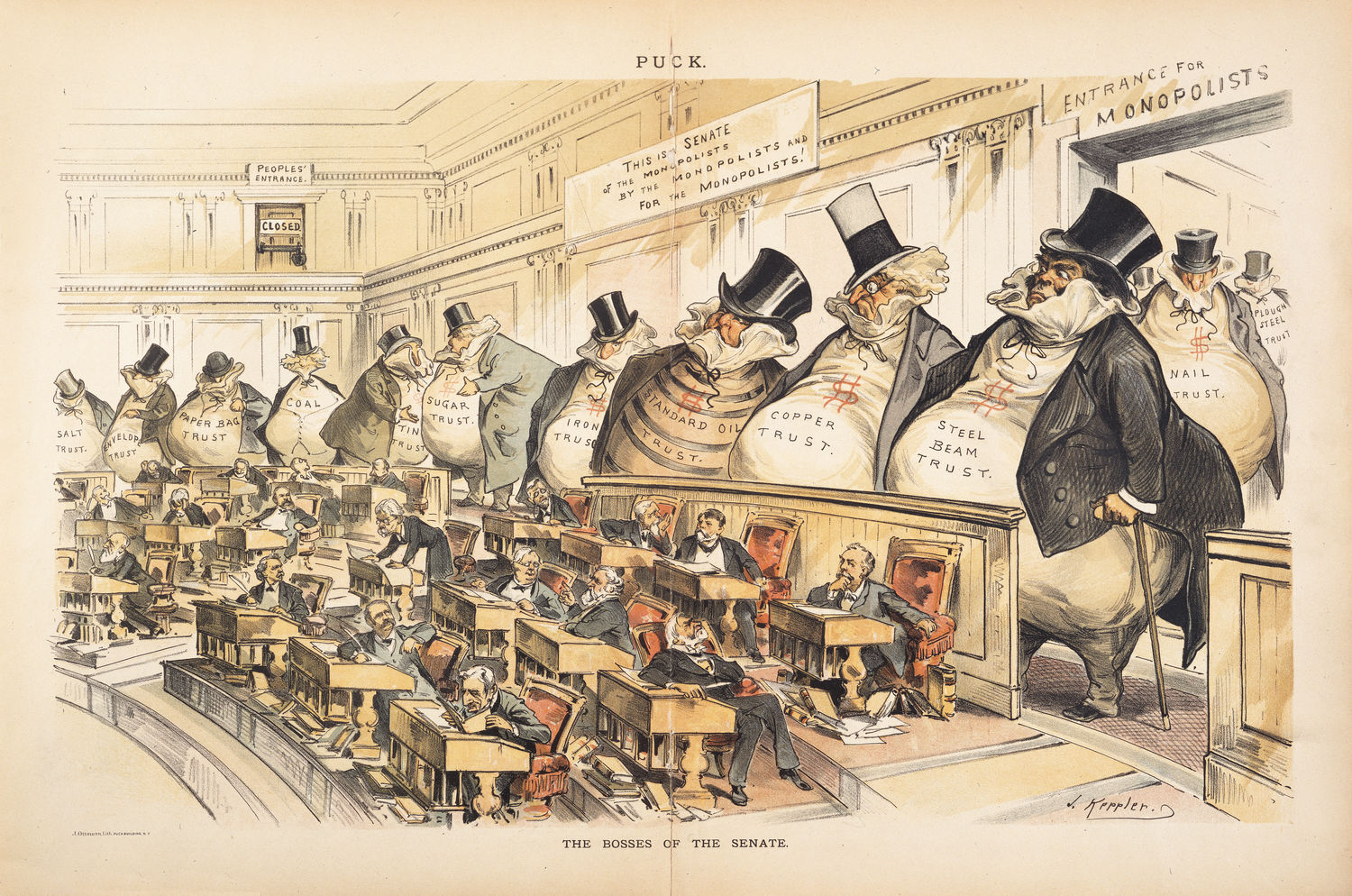

This cartoon depicts industrial monopolists as towering money bags dominating the Senate, symbolizing public fears that corporate power overshadowed democratic institutions. The sealed “people’s entrance” underscores concerns about political exclusion. While also referencing antitrust debates, it directly visualizes Gilded Age critiques of concentrated wealth and inequality. Source.

Robber Baron: A critical term describing powerful industrialists perceived as enriching themselves through exploitative business practices and anti-competitive tactics.

Some commentators believed wage labor undermined traditional republican ideals of economic independence. Others accepted wage labor as modern and unavoidable but insisted on safeguards to ensure dignity and stability. These views influenced rising support for labor organizations and political reforms.

In contrast, many business leaders defended their wealth as the product of talent, innovation, and risk-taking. They often invoked laissez-faire principles, arguing that government interference distorted markets and slowed progress.

Labor Movements and Collective Action

Workers responded to economic instability and wage pressures by forming unions that articulated alternative visions of workplace relationships. These groups advanced new claims about the rights and responsibilities of workers in an industrial society.

Key forms of collective action included:

Organizing trade unions to negotiate better wages and conditions

Launching strikes to pressure employers during contract disputes

Advocating legislation to regulate hours, safety, and child labor

Building cross-industry alliances that challenged the concentration of corporate power

While some strikes succeeded temporarily, many failed due to employer resistance, court injunctions, or state intervention. Conflict between labor and management intensified post-panic, as employers sought stability and workers sought protection from volatility.

Competing Intellectual and Cultural Perspectives

Economic downturns spurred intense debate about the causes of inequality and the proper role of government. Several schools of thought emerged:

Classical liberalism promoted unregulated markets, asserting that competition ensured efficiency and innovation.

Social Darwinism, applied to economic life, claimed inequality reflected natural hierarchies of ability and effort.

Labor republicanism maintained that concentrated wealth undermined civic virtue and democracy.

Producerism celebrated those who directly created economic value—farmers, artisans, and workers—and criticized financiers for profiting without producing.

Religious critiques, including early Social Gospel ideas, condemned harsh working conditions as morally unacceptable.

These frameworks shaped how Americans interpreted the causes and consequences of panics. For example, supporters of laissez-faire blamed downturns on misguided monetary policy or natural business cycles, while critics argued that weak protections and unchecked speculation produced preventable instability.

Government Responses and Regulatory Debate

Financial crises raised questions about whether government should intervene to stabilize markets. Some citizens demanded federal action to regulate banking, curb monopolies, and ensure fair labor practices. Others insisted that intervention would hinder economic freedom and recovery.

Debates over policy often included:

Whether the government should regulate currency and credit to prevent speculative bubbles

How tariff policies influenced industrial growth and labor markets

Whether antitrust laws were necessary to curb excessive corporate consolidation

The extent to which the state should protect workers harmed by cyclical downturns

These controversies reflected broader anxieties about modern industrial society and illuminated the deep ideological divides that shaped Gilded Age politics. Disputes over financial panics, wages, and labor ultimately helped propel later reforms in the Progressive Era, when many unresolved questions from this period finally reached the national agenda.

FAQ

Financial panics affected Americans unevenly because income stability varied widely across occupations.

Farmers often struggled with falling crop prices and limited access to credit, making it difficult to recover from downturns.

Factory workers faced mass layoffs or steep wage cuts, forcing families to rely on irregular employment.

Small business owners risked closure when banks restricted lending and customers reduced spending.

Wealthier industrialists were better insulated, as they had savings, diversified holdings, and access to private financial networks.

Workers tended to focus on grievances that worsened during periods of economic contraction.

Key concerns included:

• Wage cuts imposed to reduce employer costs

• Speed-ups, in which employers increased workloads without raising pay

• Safety standards deteriorating as firms minimised operational expenses

• Irregular hours or temporary shutdowns leaving workers without income

These grievances deepened perceptions that employers prioritised profits over worker wellbeing, strengthening support for collective action.

Newspapers played a central role in influencing how Americans interpreted labour conflicts.

Many urban papers framed strikes as threats to public order, emphasising violence or disruption rather than underlying worker grievances.

Business-aligned editors often defended employers, arguing that strikes hindered recovery.

In contrast, some labour or reform newspapers highlighted unsafe conditions, wage exploitation, and the social impact of corporate power.

These competing portrayals contributed to polarised public attitudes about the legitimacy of unions and the fairness of industrial capitalism.

Not all workers joined unions, even when conditions deteriorated.

Reasons included:

• Fear of dismissal or blacklisting by employers

• Distrust of union leadership or internal factionalism

• Belief in individual self-reliance rather than collective action

• Concerns that strikes would interrupt wages needed for family survival

Immigrant workers sometimes worried that union participation would draw unwanted attention from authorities or jeopardise community networks.

Financial crises often pushed labourers to engage more actively with political movements advocating reform.

Workers joined parties or organisations promoting currency reform, antitrust enforcement, and labour protections.

Rallies, public meetings, and petition campaigns became common ways to express frustration with corporate dominance and government inaction.

Some labourers aligned with emerging reform coalitions that challenged traditional party loyalties, seeking policies to stabilise wages and reduce economic uncertainty.

These developments reflected a growing belief that economic security required structural political change.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which financial panics in the late nineteenth century influenced debates about industrial capitalism in the United States.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid impact of financial panics (e.g., heightened public distrust of unregulated markets).

2 marks for explaining how the panic influenced debates (e.g., reformers argued that instability proved the need for government intervention).

3 marks for providing a developed explanation linking the panic to broader discussions about wages, labour rights, or corporate power.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which labour movements' responses to economic downturns reflected broader ideological debates about the role of government and corporate power in the Gilded Age (1865–1898).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1–2 marks for describing labour movements’ actions during downturns (e.g., strikes, unionisation, demands for regulation).

3–4 marks for connecting those actions to wider ideological debates, such as laissez-faire principles, Social Darwinism, labour republicanism, or critiques of monopolies.

5–6 marks for a sustained, well-supported evaluation of the extent to which labour responses reflected these debates, showing nuanced understanding of competing perspectives and the broader Gilded Age context.