AP Syllabus focus:

‘Technological advances, large-scale production, and new markets expanded industrial capitalism, accelerating economic growth and business consolidation.’

Industrial capitalism transformed the United States after 1865, as new technologies, production methods, and expanding markets reshaped business organization, encouraged large-scale consolidation, and altered economic relationships nationwide.

Industrial Capitalism After the Civil War

Industrial capitalism expanded rapidly in the decades following the Civil War, driven by structural changes in technology, production, and markets. This period witnessed the emergence of large, integrated corporations that replaced earlier small-scale enterprises. The United States became a leading industrial power as firms embraced mechanization, scientific management, and nationwide supply chains. Economic development accelerated, but so did tensions over corporate power and inequality.

Key Forces Driving Expansion

Several interconnected forces reshaped the national economy and accelerated business consolidation.

Technological advances such as the Bessemer steel process, long-distance telegraphy, and improved petroleum refining increased industrial output and lowered costs.

Large-scale production methods enabled corporations to manufacture goods more efficiently, allowing them to dominate markets and outcompete smaller rivals.

New markets—domestically integrated by railroads and expanded through international trade—gave businesses opportunities for greater profit and wider geographic reach.

Pro-growth government policies, including protective tariffs and favorable legal rulings, encouraged entrepreneurs to invest, consolidate, and innovate.

Technology and the Transformation of Production

Mechanical innovations reshaped how goods were produced and distributed. Factories became increasingly complex, relying on standardized parts, continuous-flow production, and precision engineering.

The expanding railroad network integrated regional economies, allowing firms to coordinate supply chains on an unprecedented scale. As transportation costs fell, national distribution became not only possible but essential to competitive success. The completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869 symbolized how rail lines knit the continent into an integrated national market.

Map of the route of the first transcontinental railroad, completed in 1869. The Central Pacific (red), Union Pacific (blue), and later Western Pacific (green) lines show how railroads linked western resources to eastern factories and markets. While the map focuses on this single route, it represents broader late-19th-century trends toward faster transportation and national economic integration. Source.

Industrial Capitalism: An economic system characterized by private ownership of industry, reliance on wage labor, and production for profit using mechanized, large-scale operations.

These technological systems fostered economies of scale, allowing firms to lower per-unit costs and operate more efficiently than small businesses.

Business Consolidation and Corporate Power

As production expanded, business leaders pursued new strategies for stabilizing markets, reducing competition, and increasing profits. These efforts led to the emergence of large corporations, trusts, and holding companies that dominated entire sectors of the economy.

Strategies of Integration

To control production and distribution, corporations increasingly adopted two major forms of integration:

Vertical integration, in which a company acquired every stage of production—from raw materials to transportation to retail—to reduce costs and improve control.

Horizontal integration, in which firms purchased or merged with competitors to limit competition and command larger market shares.

Trust: A business arrangement in which multiple companies in the same industry transfer shares to a single board of trustees, allowing unified control and reduced competition.

These approaches allowed industrial leaders such as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller to centralize decision-making, stabilize prices, and dominate steel, oil, and other core industries.

A key development in the 1880s and 1890s was the rise of the holding company, a corporation created solely to own stock in other companies. This structure provided a legal and organizational tool for large-scale consolidation.

Holding Company: A corporation that owns enough voting stock in other companies to control their policies and management without producing goods itself.

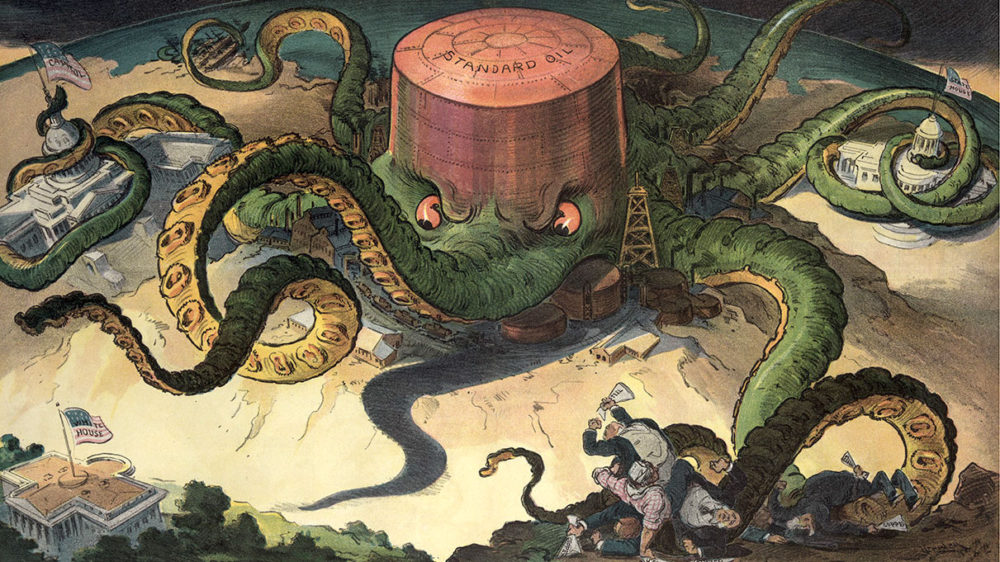

To illustrate how widely feared trusts had become as symbols of economic power: Standard Oil’s aggressive horizontal integration—buying up refineries and securing secret rebates from railroads—gave John D. Rockefeller near-total control of the refining industry.

Udo Keppler’s 1904 cartoon “Next!” shows Standard Oil as an octopus whose tentacles encircle key industries, a state capitol, and the U.S. Capitol, reaching toward the White House. The image captures contemporary anxieties that consolidated corporations could dominate markets and bend democratic institutions to their will. Because it dates from the early Progressive Era, it also reflects reformers’ backlash against the late-19th-century rise of industrial trusts, slightly extending beyond the AP time frame but illustrating its long-term consequences. Source.

Finance, Capital, and Industrial Growth

Industrial expansion required enormous capital investments for machinery, factories, and railroads. Wall Street banks and investment houses played an increasingly important role in underwriting corporate growth. Financial innovators, including J.P. Morgan, helped merge competing firms, reorganize struggling industries, and stabilize markets. The rise of the modern corporation depended on access to capital markets that could mobilize resources at a national scale.

New Markets and National Integration

The creation of national markets transformed the American economy. Railroads linked isolated regions, allowing goods to move quickly and reliably across thousands of miles. Improved communication systems such as the telegraph accelerated information flows, enabling firms to coordinate prices, production, and distribution across vast distances. Larger markets rewarded firms that could produce cheaply and consistently, intensifying pressures toward consolidation.

Measuring Change: Economic and Social Effects

Industrial consolidation reshaped not only how businesses operated but also how Americans experienced economic life.

Economic Growth and Increased Productivity

Industrial output soared between 1865 and 1898, driven by mechanization, capital investment, and corporate organization. The United States surpassed many European competitors in steel, oil, and manufactured goods. Consolidation produced more stable pricing, larger workforces, and greater overall productivity, contributing to national economic growth.

Concentration of Wealth and Corporate Influence

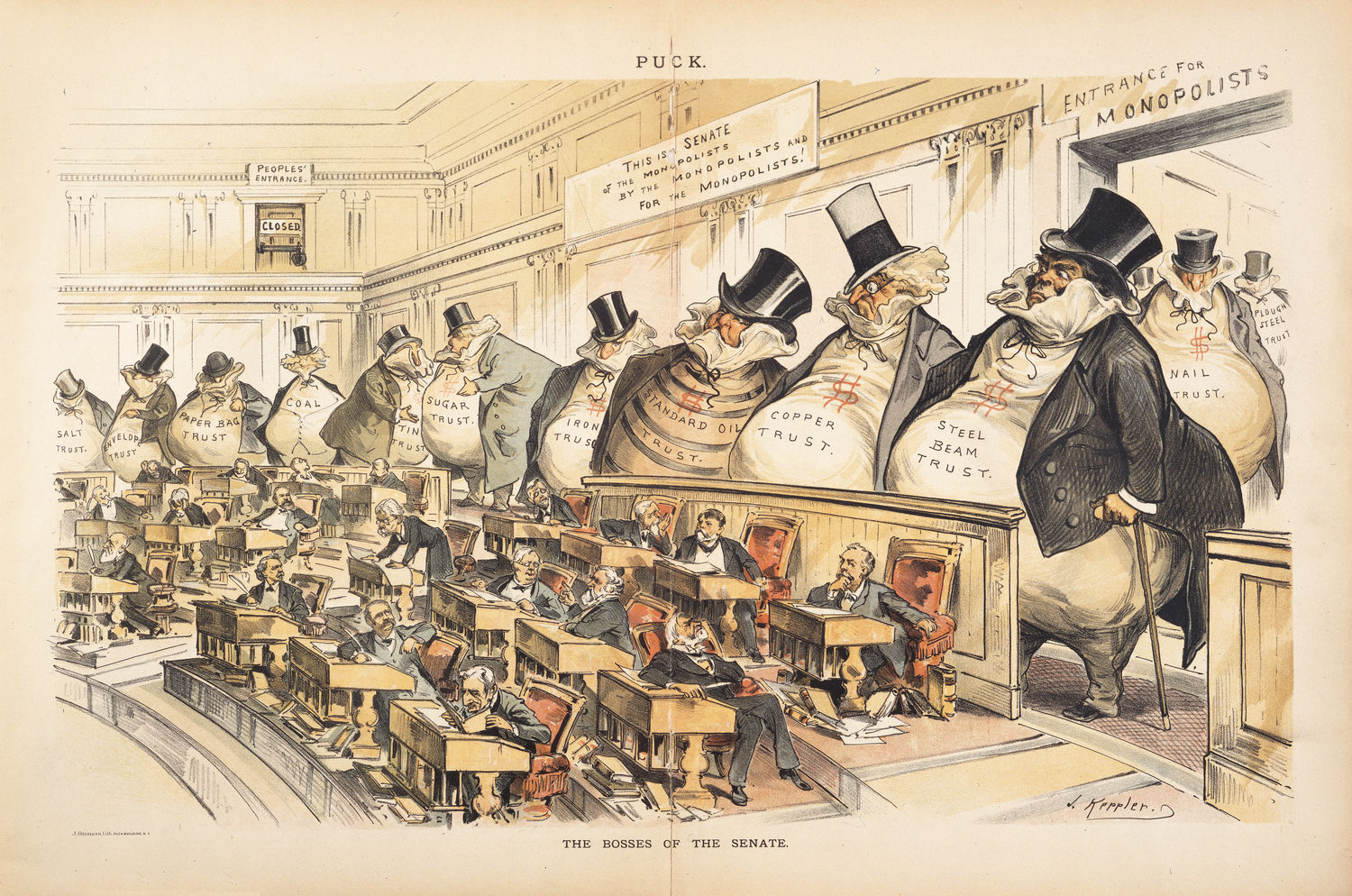

As large corporations amassed wealth, economic power became increasingly concentrated. Many Americans viewed the rise of “captains of industry” as a sign of progress, while others criticized “robber barons” for exploiting workers and manipulating markets. Critics warned that concentrated corporate wealth translated into outsized political influence over legislatures and the courts.

Joseph Keppler’s 1889 cartoon “The Bosses of the Senate” portrays enormous money-bag figures labeled with major industries standing behind the senators’ desks. A blocked “People’s Entrance” and the slogan “This is the Senate of the Monopolists by the Monopolists and for the Monopolists” underscore fears that big business had captured national politics. The cartoon includes specific industry labels and details not mentioned in the syllabus, but these elements all reinforce the central theme of monopoly power and corporate influence over government. Source.

Changing Labor and Market Dynamics

Large-scale corporate structures altered labor relations and market competition. Wage labor became more specialized, hierarchical, and closely supervised. Smaller firms struggled to compete with massive enterprises capable of undercutting prices or controlling supply chains. These shifts contributed to labor unrest, antitrust movements, and a growing demand for government intervention.

The Broader Significance of 1865–1898

The expansion of industrial capitalism and the consolidation of business power between 1865 and 1898 marked a profound transformation in American economic life. New technologies, large-scale production systems, and national markets permanently altered the balance between competition and corporate control. Industrial consolidation generated both prosperity and social tension, shaping political, economic, and cultural debates that would define the Gilded Age and beyond.

FAQ

States increasingly adopted permissive incorporation laws that made it easier to create and merge corporations across state lines.

These laws allowed companies to issue more stock, purchase other firms legally, and centralise management under boards of directors.

Some states, especially New Jersey and later Delaware, competed for corporate registrations by offering low taxes and flexible rules, encouraging nationwide consolidation.

Courts had begun challenging the legal basis of trusts, making them vulnerable to antitrust suits and state-level restrictions.

Holding companies offered a legally safer alternative because they owned stock rather than relying on trustee arrangements.

They also provided clearer, centralised control over multiple subsidiaries, which improved coordination and reduced managerial conflicts within large corporate empires.

As railroads linked regional economies, firms no longer competed locally but faced rivals across the country.

This encouraged businesses to lower prices, invest in mechanisation, and scale up production to remain viable.

Many small firms failed to adapt, which further accelerated consolidation as larger companies absorbed weaker competitors.

Expanding companies required more complex hierarchies to manage nationwide operations.

They developed specialised departments for accounting, purchasing, marketing, and workforce supervision.

Middle managers emerged as a new professional class, coordinating between top executives and shop-floor workers to maintain efficiency and standardise production.

Widespread fears that monopolies restricted competition and controlled prices led newspapers, labour unions, and reformers to campaign for government intervention.

Critics argued that concentrated wealth allowed corporate leaders to influence political decisions, undermining democratic accountability.

These debates laid essential groundwork for later legislative actions, even before federal regulators had meaningful authority to challenge large corporations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one factor that contributed to the rise of business consolidation in the United States between 1865 and 1898, and briefly explain how it encouraged the growth of large corporations.

Mark Scheme:

• 1 mark for correctly identifying a relevant factor (e.g. technological advances, economies of scale, national markets, pro-growth government policies).

• 1 mark for explaining how the factor contributed to consolidation.

• 1 mark for providing a precise, historically accurate link to the growth of large corporations (e.g. railroads enabling national distribution, technology lowering production costs, government rulings favouring corporate expansion).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how industrial capitalism between 1865 and 1898 transformed both the structure of American businesses and the distribution of economic power. Use specific historical examples in your response.

Mark Scheme:

• 1–2 marks for describing changes to business structure (e.g. rise of corporations, vertical and horizontal integration, creation of trusts and holding companies).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how these developments shifted economic power (e.g. concentration of wealth, dominance of national markets, influence over politics).

• 1–2 marks for using accurate, relevant examples (e.g. Standard Oil, Carnegie Steel, J. P. Morgan’s financial consolidation activities).