AP Syllabus focus:

‘Financial panics and downturns shaped debates over labor, wages, and the proper relationship between workers, employers, and government.’

Economic instability in the late nineteenth century reshaped American debates over labor, wages, workplace power, and the responsibilities of government during recurring financial crises and industrial conflict.

Changing Labor Conditions in an Unstable Economy

During Period 6, recurring financial panics—especially those of 1873 and 1893—intensified national discussions about the nature of work and the balance of power between labor and capital. These downturns occurred as industrial capitalism expanded, heightening tensions surrounding wage labor, job security, and economic fairness.

The Structure of Wage Labor

The rise of industrial wage labor created new dependencies for American workers. As factories replaced earlier independent or artisanal work structures, laborers faced long hours, low pay, and dangerous working environments. Growing industrial scale meant individual workers had less bargaining power.

Because industrialization produced a new national labor market, layoffs linked to market cycles became more common, reinforcing debates about the vulnerability of wage earners in a capitalist economy.

Wage Labor: A labor system in which workers sell their time and effort for wages rather than owning the tools or products of their work.

Throughout these shifts, many Americans questioned whether industrial capitalism offered opportunity or entrenched exploitation.

Financial Panics and Their Effects on Work and Wages

Financial crises struck hard at workers and employers alike, but their impacts were distributed unequally.

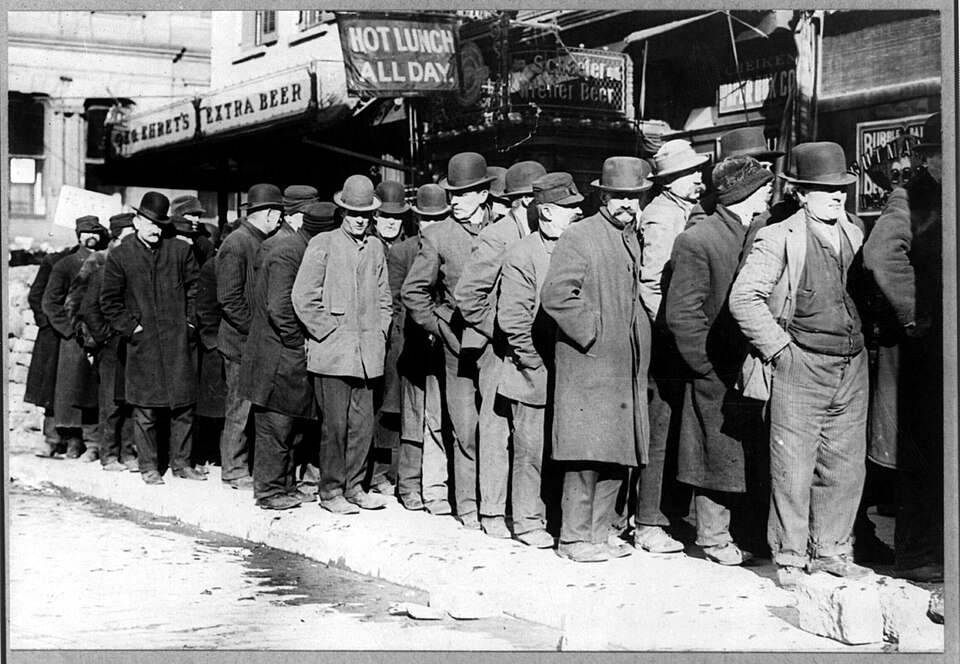

Men wait in a breadline during a period of economic distress, reflecting how unemployment and wage loss left industrial workers dependent on charity. The scene illustrates the human consequences of financial panics. Although taken in 1910, it closely parallels Gilded Age economic hardship. Source.

The Panic of 1873

• Triggered by railroad overbuilding and the collapse of major financial firms.

• Sent shockwaves through industries reliant on credit and rapid expansion.

• Led to wage cuts, layoffs, and major strikes, such as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

The Panic of 1893

• Sparked by railroad bankruptcies, declining agricultural prices, and unstable financial markets.

• Produced one of the nineteenth century’s worst depressions.

• Forced employers to slash wages even as living costs remained unstable.

Workers interpreted these panics as evidence that unfettered capitalism created cycles of instability that harmed working families. Employers, however, often defended reductions as unavoidable responses to market conditions.

Competing Economic Perspectives

Financial downturns deepened ideological divides over the causes of instability and the best remedies for labor-market inequities.

Employer and Business Perspectives

Many business leaders argued that:

• Laissez-faire principles allowed efficient markets to allocate resources.

• Wage cuts during downturns were necessary to keep firms afloat.

• Government intervention would distort market signals and slow recovery.

• Labor unions threatened economic stability by demanding wages unrelated to productivity.

This viewpoint aligned closely with classical liberalism and the belief that competition—however harsh—ultimately promoted long-term economic growth.

Worker and Reform Perspectives

Workers and reformers offered contrasting explanations:

• They saw wage cuts and layoffs as symptoms of structural economic imbalance.

• Large corporations, trusts, and railroads appeared to manipulate markets, creating artificial scarcity or instability.

• The absence of legal protections left workers vulnerable to exploitation.

• Many questioned whether the benefits of industrial capitalism were shared fairly.

These ideas fueled labor organizing and reform movements that challenged the concentration of economic power.

Labor Movements and Public Debate

Labor activism in this period grew partly in response to recurring downturns that exposed the precariousness of wage labor.

Union Responses

Major unions, including the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor (AFL), developed strategies to secure better wages and safer conditions. Their demands intensified when panics pushed employers to impose wage cuts.

Unions also publicized how economic cycles disproportionately harmed workers, reinforcing calls for new policies.

Collective Bargaining: Negotiation between organized workers and employers to determine wages, hours, and working conditions.

Unions used collective bargaining to challenge managerial authority during both boom and bust years.

This cartoon portrays organized labor as a force advancing societal progress despite resistance from employers. The exaggerated boot emphasizes the growing power of unions. Although created in 1913, it reflects themes central to Gilded Age labor debates. Source.

Strikes and Public Perception

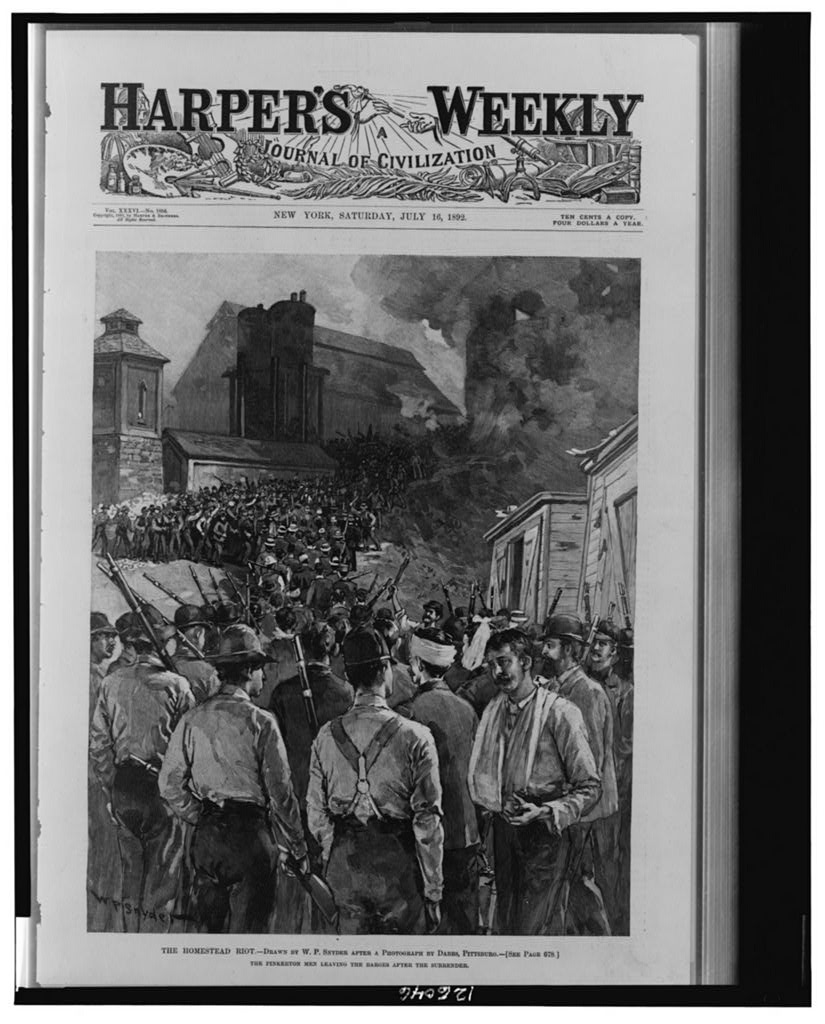

Strikes during economic downturns reflected the desperation of workers who faced shrinking wages and rising unemployment. Notable conflicts, such as the Homestead Strike (1892) and Pullman Strike (1894), highlighted deep tensions:

This engraving depicts the violent confrontation at Homestead between striking steelworkers and Pinkerton agents. It visualizes the intensity of Gilded Age labor conflict and the willingness of employers to use private force. The image includes scene-specific details that exceed the syllabus but clearly illustrate main themes of industrial labor tensions. Source.

• Employers framed strikes as threats to order and economic progress.

• Workers framed them as necessary defenses of dignity and livelihood.

• Government intervention—often on behalf of employers—reinforced perceptions of unequal power.

These events shaped national debates about whether government should remain neutral, support business stability, or protect workers’ rights.

Government’s Role in Labor and Economic Stability

Disagreement over the proper role of government lay at the heart of debates shaped by financial panics.

Minimal-State Advocates

Supporters of limited government believed:

• Market competition would correct downturns without state action.

• Intervention risked moral hazard and hindered recovery.

• Aid to the unemployed or regulation of industry was inappropriate and potentially unconstitutional.

Reformers and Pro-Intervention Voices

Others argued that:

• Industrial capitalism produced new social responsibilities for government.

• Regulation of working conditions, corporate power, and financial systems was necessary.

• Economic downturns revealed the insufficiency of relying solely on market forces.

These conflicting visions would continue into the Progressive Era, but their origins were firmly rooted in the labor tensions and panics of Period 6.

FAQ

Skilled workers often had greater bargaining power and were more likely to retain employment or secure modest wage protections during downturns, as their specialised abilities were harder to replace.

Unskilled labourers, by contrast, faced immediate layoffs and steep wage reductions, as employers viewed their roles as interchangeable and expendable.

These differences sometimes created divisions within the labour movement over strategy and priorities.

Reformers argued that recurring crises showed the system concentrated too much economic power in corporations and railroads.

They claimed instability stemmed from overproduction, speculative investment, and a lack of regulation.

Some insisted that without government oversight, cycles of boom and bust would continue to disproportionately harm wage earners.

Many workers believed government intervention on behalf of business signalled that political institutions were controlled by corporate interests.

This perception fostered distrust in state and federal authorities and encouraged support for reform movements advocating greater protection of workers’ rights.

Middle-class observers were divided: some viewed intervention as necessary to preserve order, while others criticised it as evidence of systemic inequality.

Public opinion often shifted depending on the severity of the crisis.

During deep downturns, sympathy for workers increased as many families experienced hardship, making union demands appear reasonable.

However, when strikes disrupted transport or essential services, newspapers and middle-class citizens sometimes blamed unions for worsening instability.

Because no federal safety net existed, debates focused on whether poverty during downturns reflected personal failure or structural economic forces.

Charity-based aid remained dominant, but discussions grew about whether state or municipal governments should intervene during mass unemployment.

These debates laid groundwork for later Progressive Era policies advocating more formal social welfare mechanisms.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which financial panics in the late nineteenth century influenced debates over the relationship between workers and employers, and briefly explain why.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for identifying a valid effect of financial panics (e.g., wage cuts, unemployment, labour unrest, strikes).

• 1 mark for linking the panic to a shift in debates over worker–employer relations (e.g., employers defending wage reductions; workers arguing capitalism was unstable).

• 1 mark for explaining why this influenced the debate (e.g., evidence of exploitation, justification for union organising, reinforcement of laissez-faire arguments).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how economic downturns such as the Panics of 1873 and 1893 contributed to competing perspectives on industrial capitalism between business leaders and labour reformers in the period 1865–1898. In your answer, refer to specific developments in labour relations, wage labour, or government policy.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 1 mark for describing economic instability during the Panics of 1873 and/or 1893.

• 1–2 marks for explaining business leaders’ perspectives (e.g., justification of wage cuts, defence of laissez-faire, belief that market forces should be allowed to operate).

• 1–2 marks for explaining labour or reform perspectives (e.g., belief that wage labour was insecure, corporations manipulated markets, call for regulation or unionisation).

• 1 mark for using specific evidence (e.g., Homestead Strike, wage cuts, expansion of wage labour, debates over government intervention).