AP Syllabus focus:

‘New production and transportation systems consolidated agriculture; instability and market pressures spurred cooperative and political responses from farmers.’

Late nineteenth-century agriculture transformed as national markets expanded, technologies spread, and new transportation systems integrated farms into a volatile economy that drove farmers toward collective organization and political activism.

National Market Integration and Agricultural Consolidation

The post–Civil War period witnessed sweeping changes that bound American farmers to a rapidly nationalizing economy. New production and transportation systems reshaped how crops were grown, shipped, and sold across an increasingly interconnected nation.

Rising Mechanization and the Logic of Scale

Improved machinery such as steel plows, reapers, and threshers heightened output and encouraged larger farm operations. These innovations lowered labor needs, widened cultivated acreage, and knit rural producers more tightly into national commodity markets.

Mechanization boosted yields but required capital investment, increasing farmers’ dependence on credit.

Greater market orientation meant farm income fluctuated with national supply and demand rather than purely local conditions.

Large, mechanized farms often outcompeted smaller producers, fostering a sense of consolidation in agriculture.

As farms scaled up, farmers confronted high start-up costs and ongoing expenses tied to equipment maintenance, interest payments, and fluctuating crop prices.

Transportation Networks and Market Dependence

Railroads as Gatekeepers of Market Access

Railroads were essential for moving crops to distant urban and industrial markets.

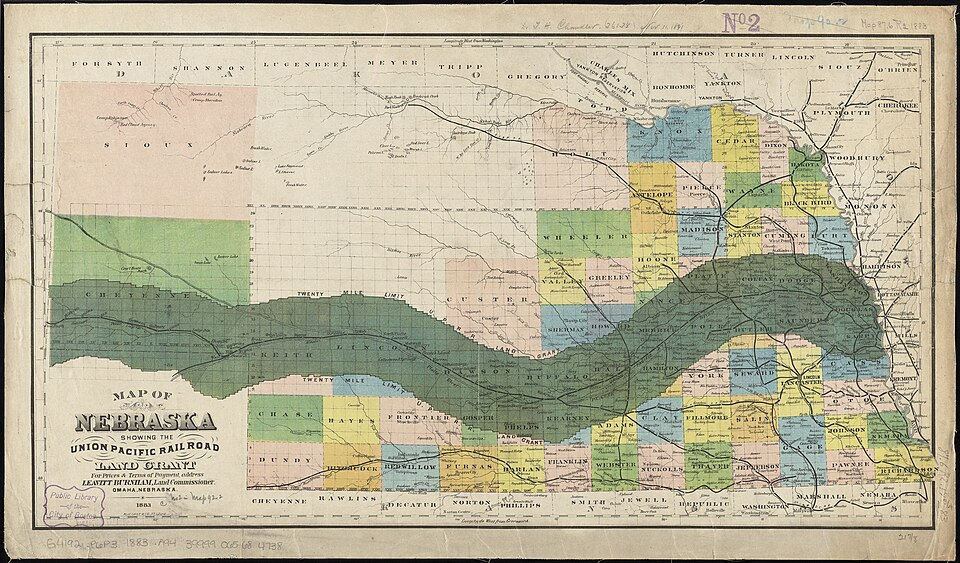

This 1883 map shows how Union Pacific rail lines and land grants opened agricultural regions to national markets, illustrating farmers’ dependence on long-distance transportation systems. Additional geographic and promotional details appear that extend beyond syllabus requirements but help contextualize regional development. Source.

Yet their dominance made farmers economically vulnerable.

Railroad companies set freight rates, often charging rural shippers more due to a lack of competition.

Warehouse operators and grain elevator companies also controlled storage fees, shaping farm profitability.

National transportation networks increased exposure to faraway market shocks, magnifying local economic instability.

Farmers perceived these transportation and shipping systems as monopolistic, a term used to describe businesses exerting excessive control over prices or market access.

Monopoly: A market condition in which a single company or a small group of companies controls prices and access, limiting competition.

Although improved transportation integrated regions, it also intensified frustrations over unequal economic power.

Price Instability and Market Pressures on Farmers

Overproduction and Global Competition

Expanding acreage and mechanized output contributed to overproduction, which pushed down crop prices in increasingly competitive global markets. Even as productivity rose, net farm income often fell.

Rising global grain supply depressed prices throughout the 1870s–1890s.

Farmers’ fixed costs (mortgages, equipment, shipping fees) remained high even when market prices collapsed.

Many farmers struggled to repay loans, facing foreclosure or deepening debt cycles.

Deflation and the Burden of Debt

Deflation in the late nineteenth century increased the real value of debts, making repayment harder. The mismatch between falling crop prices and stable or rising interest rates created acute financial strain.

Farmers interpreted these pressures as structural rather than personal failures, prompting collective economic and political responses aimed at reforming market conditions.

Farmer Organization and Cooperative Responses

Building Local and Regional Cooperatives

In reaction to market consolidation, farmers developed organizations to assert greater control over economic life.

The Grange (Patrons of Husbandry) formed after the Civil War to promote social support, cooperative purchasing, and educational programs.

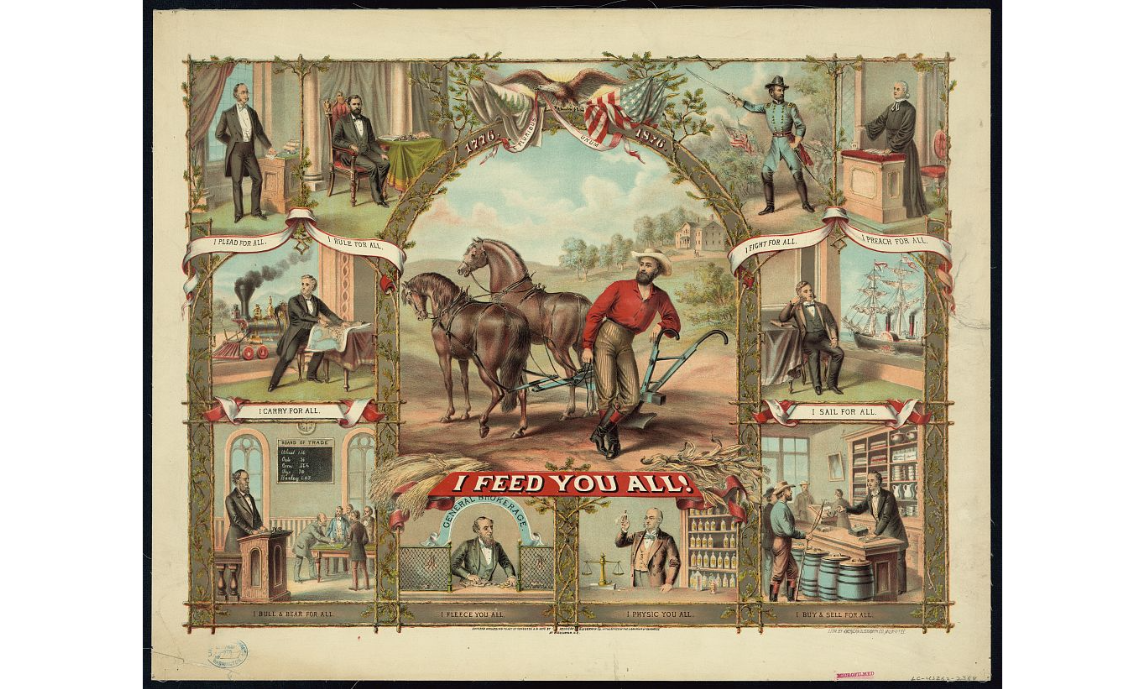

This lithograph reflects the Granger movement’s message that farmers sustained the nation even as they confronted monopolistic power structures. Symbolic patriotic and professional imagery appears beyond syllabus essentials, illustrating the broader cultural meaning attached to agrarian identity. Source.

Granger cooperatives attempted to bypass middlemen by operating their own stores, grain elevators, and warehouses.

Through state-level activism, Grangers advocated Granger Laws regulating railroad rates and grain storage fees.

Cooperative: A business or service owned collectively by its members, who share benefits and decision-making authority.

These cooperative efforts aimed to reduce costs and rebalance market power but often struggled against entrenched corporate and financial interests.

The Farmers’ Alliances and Broader Economic Strategies

The Farmers’ Alliances, emerging in the 1870s–1880s, expanded organizational reach beyond earlier cooperative models.

The Southern and Northwestern Alliances recruited millions, focusing on rural education, credit reform, and railroad regulation.

The proposed subtreasury plan sought federal warehouses to store crops and provide low-interest loans, allowing farmers to wait for better market prices.

Alliances promoted collective bargaining, political mobilization, and economic literacy to reduce dependency on banks and railroads.

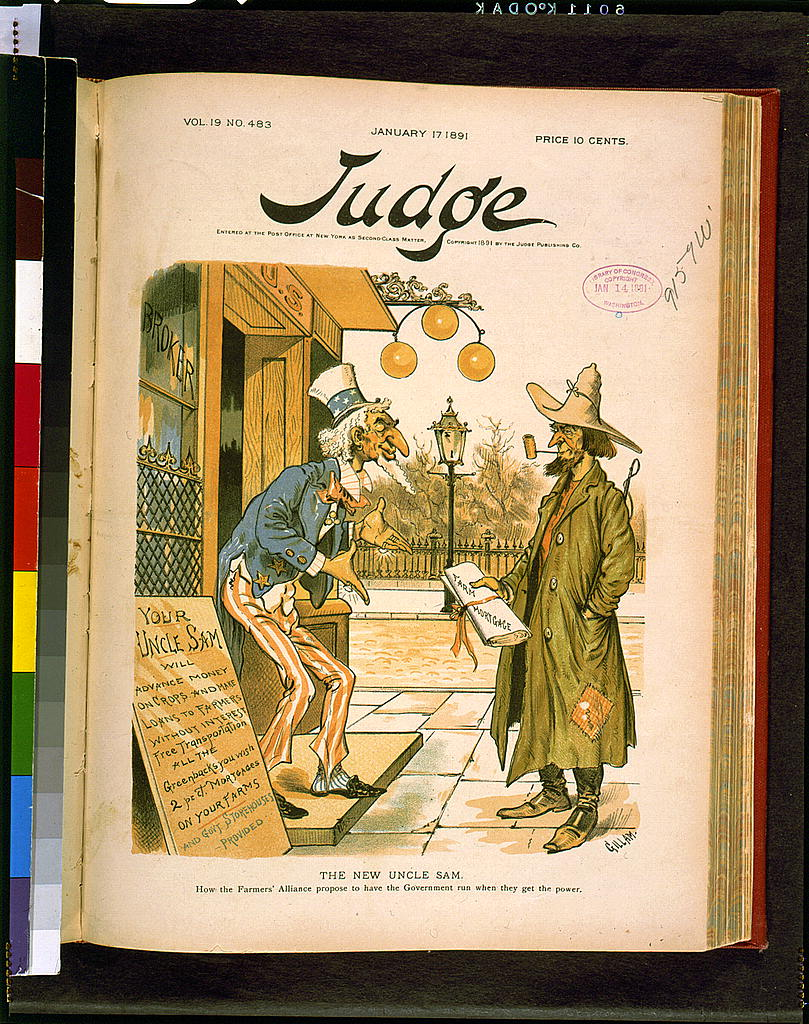

This 1891 cartoon critiques Farmers’ Alliance proposals for government intervention in credit and currency, reflecting public anxieties about expanding federal roles. The drawing includes ethnically stereotyped imagery not required by the syllabus but valuable for understanding contemporary political rhetoric. Source.

These organizations reflected farmers’ belief that only systemic reform could stabilize agricultural life within a national market.

Political Mobilization and Demand for Government Intervention

From Economic Protest to the People’s Party

By the early 1890s, persistent instability and perceived corporate dominance propelled many farmers into national politics.

Alliance activism helped form the People’s (Populist) Party, which championed expanded federal authority to regulate transportation, currency, and credit.

Populists supported bimetallism, the use of both silver and gold to expand the money supply, which they believed would ease debt burdens.

The party advocated federal ownership of railroads, graduated income taxes, and direct election of senators to limit elite influence.

Political mobilization signaled a shift from localized cooperative responses toward broad national reform efforts aimed at reshaping the relationship between farmers, markets, and government.

Lasting Significance of Farmer Responses

Although the Populists ultimately lacked long-term electoral success, their demands highlighted deep tensions within an industrializing economy. Their critiques of market consolidation, calls for regulatory oversight, and push for monetary reform reflected widespread rural frustration and helped lay groundwork for later Progressive Era reforms.

Farmers’ experiences in a nationalized agricultural market thus reveal significant changes between 1865 and 1898, demonstrating how technological and transportation systems transformed economic life and intensified collective responses to structural pressures.

FAQ

American farmers increasingly competed in international grain markets as transport and communication advances linked global supply chains.

Large harvests in Russia, Canada, and Argentina depressed world prices, making American crop values unstable and often insufficient to cover debt repayments.

Because farmers had little influence over global supply, they struggled to adapt quickly, heightening their sense of vulnerability within the expanding national market.

Grain elevators often operated as regional monopolies, setting storage and grading terms that farmers could not negotiate.

Problems included:

• Unfair grading practices that undervalued high-quality grain

• Storage fees that rose during periods of high demand

• Delayed payments that forced farmers to rely on further credit

These factors deepened farmers’ distrust of the wider commercial system that mediated access to national markets.

Environmental shocks intensified the economic fragility created by national price swings.

Droughts in the 1880s forced farmers to borrow more heavily to purchase seed and equipment, locking them further into debt cycles.

Crop failures also meant they faced foreclosure sooner when market prices were unfavourable.

The combination of ecological and market pressures strengthened support for cooperative and regulatory reform.

Advances in postal delivery, rural newspapers, and telegraph lines helped farmers share information quickly across vast distances.

These networks enabled:

• Rapid spread of cooperative strategies

• Coordination of regional and national meetings

• Circulation of economic critiques and reform proposals

Better communication helped transform scattered frustrations into organised movements like the Farmers’ Alliances.

Many rural banks had limited capital and charged high interest rates, making borrowing expensive and risky.

When crop prices fell, farmers struggled to repay loans, and local banks frequently foreclosed, worsening rural instability.

This experience encouraged support for federal credit alternatives, such as the subtreasury plan, which promised lower rates and greater financial security independent of private lenders.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the expansion of national transportation networks affected farmers in the late nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark

• Identifies a valid impact, such as increased dependence on railroads or exposure to national price fluctuations.

2 marks

• Provides a clear explanation of the impact, for example noting how freight rates or storage fees raised farmers’ costs.

3 marks

• Offers further accurate detail, such as describing monopolistic practices by railroads or how national transportation systems heightened vulnerability to distant market changes.

(4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which farmers’ cooperative and political movements between 1865 and 1898 represented a response to economic instability created by national market integration. Use specific historical evidence to support your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks

• Gives a generally accurate explanation linking economic instability (falling prices, overproduction, debt, monopolistic transport networks) to the formation of cooperative and political movements.

• Uses at least one specific piece of evidence (e.g., the Grange, Farmers’ Alliances, Granger Laws, subtreasury plan, the Populist Party).

5 marks

• Provides a more developed analysis that clearly connects market pressures to changing organisational strategies.

• Explains how these movements sought structural reform, such as government intervention in credit or railroad regulation.

6 marks

• Presents a well-structured, analytical response addressing the extent of the connection between economic instability and farmer mobilisation.

• Integrates multiple specific examples (e.g., Grange cooperatives, Alliance economic programmes, Populist monetary reform).

• Shows nuanced understanding, such as noting limits of these responses or acknowledging both economic and political motivations.