AP Syllabus focus:

‘As migrants increased and the bison population declined, competition for land and resources among settlers, American Indians, and Mexican Americans intensified into violent conflict.’

Growing migration into the West after the Civil War intensified struggles for scarce land, water, minerals, and especially the declining bison herds, heightening conflict among diverse groups.

Competition for Western Land and Natural Resources

The post–Civil War West became a contested region as expanding settlement and resource extraction drew diverse populations into closer and often hostile contact. Land, water, and bison—the central pillars of Indigenous subsistence and cultural life—were profoundly reshaped by federal policy and private economic interests. These pressures reflected broader national trends of industrial capitalism and migration.

Expansion of Settler Populations and Demands on the Land

Farmers, ranchers, miners, and railroad companies moved westward in greater numbers during the late nineteenth century, supported by federal incentives such as the Homestead Act and railroad land grants. Their presence dramatically increased demand for arable land, grazing space, and access to mineral-rich regions.

Settlers claimed property through homesteading and purchase, often disregarding or violating existing Indigenous and Mexican American land use patterns.

Ranching interests sought open-range grazing, which encroached on traditional hunting territories and communal lands.

Mining booms brought large corporate enterprises whose extraction methods disrupted water sources and degraded shared environments.

Competition escalated because Western ecosystems were not capable of supporting unrestricted use by all groups simultaneously. As more settlers arrived, conflicts sharpened over water rights and grazing lands, especially during periods of drought.

The Central Role of the Bison and Its Rapid Decline

For many Plains tribes—particularly the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa—the bison formed the foundation of economic, social, and spiritual life. Migrants entering the West, however, contributed to a devastating decline in bison herds.

Bison Extermination: The large-scale destruction of bison herds in the late nineteenth century, driven by overhunting, market demand, and U.S. military strategy.

Commercial hunters sought hides for industrial uses, while railroad routes enabled easy transport of carcasses and encouraged recreational shooting. Industrial capitalism transformed the bison into a commodity, accelerating the pace of destruction. By the 1880s, only a few hundred bison remained.

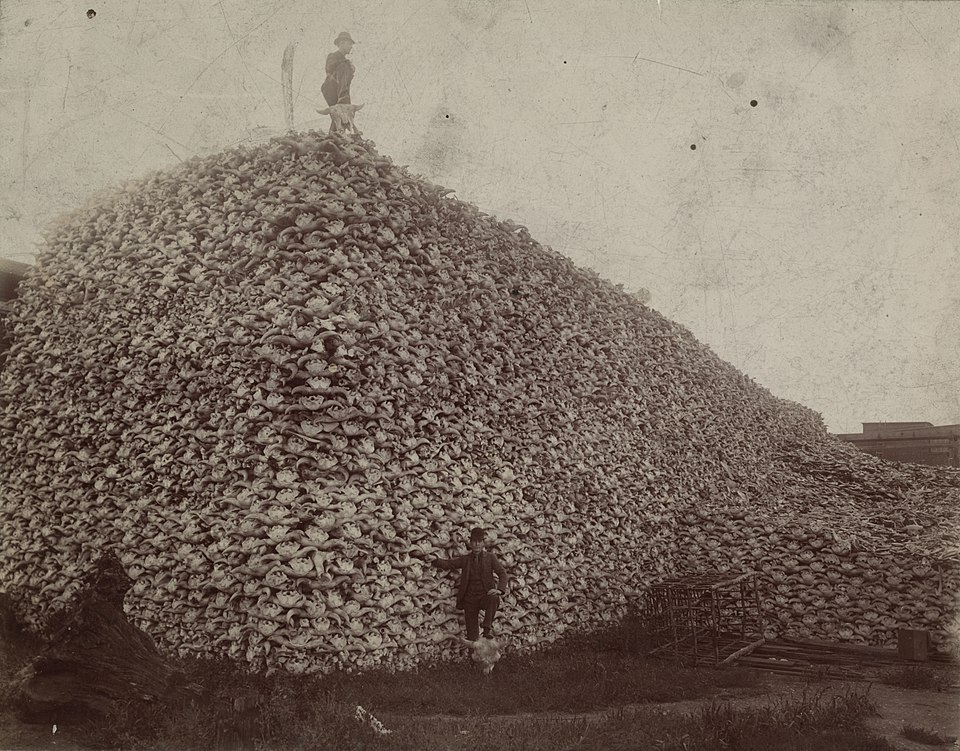

Photograph of a huge pyramid of American bison skulls awaiting industrial processing around 1892. It illustrates the extraordinary scale of commercial slaughter that nearly eliminated bison herds central to Plains Indian life. Extra context is visible, as the bones were processed into fertilizer and other industrial products, reflecting broader economic forces beyond the syllabus scope. Source.

The near-extinction of the bison undermined Indigenous autonomy by eliminating a primary food source and economic base. It also weakened resistance to U.S. military campaigns, since dependent communities faced starvation, reduced mobility, and increased vulnerability.

Conflict Among Settlers, American Indians, and Mexican Americans

As the syllabus emphasizes, rising migration intensified competition that frequently erupted into violence. These conflicts stemmed from fundamentally different understandings of property, land use, and sovereignty.

Tensions Between Settlers and American Indians

Many Indigenous nations resisted the encroachment of settlers who occupied lands guaranteed by earlier treaties. Armed clashes emerged across the Great Plains, Southwest, and Northwest. Settlers often portrayed these conflicts as obstacles to progress, while Indigenous groups defended long-held territories crucial to their cultural survival.

Key factors that drove conflict included:

Expansion of railroads, which cut through hunting grounds and brought military outposts.

Resource extraction, which restricted Indigenous access to water, timber, and minerals.

U.S. military intervention, used to suppress resistance and force Indigenous relocation.

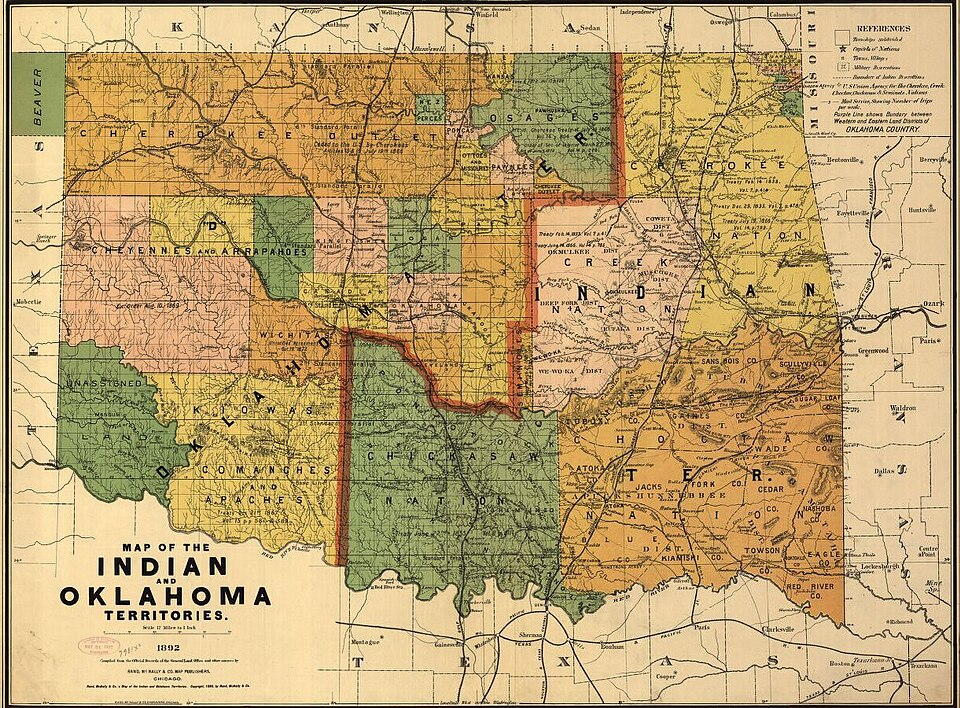

After major defeats for Indigenous groups, such as the Red River War and the Nez Perce conflict, federal authorities increasingly confined tribes to reservations, intensifying hardship and reducing their control over land and resources.

A late nineteenth-century map illustrating the territorial divisions imposed on Native nations and areas opened for non-Native settlement. It reinforces the notes’ discussion of reservation confinement and reduced Indigenous land control. Additional features such as railroads and towns extend beyond the syllabus but help contextualize regional geography. Source.

Mexican American Land Loss and Local Conflicts

Mexican Americans in the Southwest experienced similar pressures. Despite the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo’s guarantees, many lost access to land through legal manipulation, restrictive property laws, or direct seizure. Anglo settlers, cattle barons, and speculators claimed lands used communally for grazing and farming.

Courts often refused to recognize older Spanish and Mexican land grants.

Vigilante violence and intimidation targeted communities resisting displacement.

Groups such as Las Gorras Blancas resisted enclosure of communal lands by cutting fences and confronting large ranching interests.

These conflicts reflected deeper debates over cultural autonomy, property rights, and racial hierarchy in the late nineteenth-century West.

Environmental Transformation and Heightened Competition

Waves of migrants altered Western ecosystems in ways that intensified competition. Farming and ranching consumed water supplies, mining disrupted landscapes, and railroad construction fragmented habitats. Environmental degradation compounded tensions as groups fought over dwindling resources.

Overgrazing on the plains created disputes between cattle ranchers and sheep herders.

Irrigation projects diverted water from Indigenous and Mexican American communities.

The collapse of the bison population forced tribes to rely on government rations, shifting power toward federal authorities and settlers.

These transformations reveal how ecological change and human conflict were tightly intertwined.

Violent Encounters and Shifting Power Dynamics

Violence manifested in battles, raids, and retaliatory attacks, but also in systemic and state-supported forms. The U.S. government framed resource conflict as a security issue, justifying military presence and policies that advanced settler interests.

Military campaigns targeted Indigenous resistance and sought to secure land for settlement.

Local militias and vigilantes enforced racialized hierarchies and property claims.

Federal policy increasingly prioritized settler expansion over Indigenous or Mexican American rights.

As competition for land and resources intensified, power shifted decisively toward settlers backed by state authority, reshaping the social and political order of the West.

FAQ

Railroads created fixed transport corridors that cut directly through hunting grounds, water sources, and communal lands. This made conflict more likely by concentrating settlement and commercial activity along narrow strips of territory.

They also enabled mass shipments of hides and bones, encouraging large-scale bison slaughter.

Additionally, railroads attracted towns, military posts, and speculative land claims, intensifying pressure on Indigenous and Mexican American communities.

Many settlers viewed land as a commodity to be owned privately, while numerous Indigenous groups understood land collectively, tied to seasonal movement or spiritual significance.

Mexican American communities frequently relied on communal grazing or village-based landholding patterns, which settlers misinterpreted as evidence of weak property rights.

These divergent land cultures led each group to see the others’ practices as either illegitimate or threatening.

Control of water meant control of farming, ranching, milling, and transport routes. Settlers often diverted streams, built irrigation ditches, or dammed waterways to concentrate resources for their own use.

This restricted Indigenous and Mexican American groups from maintaining agricultural plots, watering livestock, or sustaining traditional practices.

Water monopolisation frequently acted as a tool for asserting long-term economic dominance.

Periodic droughts in the late nineteenth century lowered river levels and reduced available grazing land. When resources shrank naturally, competition became harsher.

Wildfires, harsh winters, and cyclical grassland decline further limited what communities could share.

Environmental strain magnified disputes over access, making armed confrontation or legal battles more likely.

Local armed groups often intervened when formal law enforcement favoured settlers or failed to act. Vigilantes commonly enforced racial hierarchies by intimidating Mexican American and Indigenous residents.

They targeted fence-cutters, communal landholders, or hunting parties viewed as trespassers.

Such groups blurred the line between policing and private coercion, allowing settlers to advance land claims through force rather than negotiation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the decline of the bison contributed to increased conflict between American Indian groups and settlers in the late nineteenth-century West.

Mark scheme:

1 mark: Identifies a valid effect of bison decline (e.g., loss of a key food source, undermining of Indigenous autonomy).

1 mark: Explains how this effect increased tension or competition (e.g., greater reliance on contested resources, increased vulnerability).

1 mark: Clearly links the decline of the bison to heightened conflict with settlers or the U.S. government (e.g., settlers expanding into former hunting grounds, military using bison destruction strategically).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which competition for land and resources was the main cause of violent conflict among settlers, American Indians, and Mexican Americans in the post–Civil War West.

Mark scheme:

1 mark: Provides a clear argument addressing the extent to which resource competition caused conflict.

1–2 marks: Uses specific evidence about competition for land, water, minerals, or bison to support the argument.

1–2 marks: Acknowledges and explains additional factors contributing to conflict, such as cultural misunderstandings, racial hierarchies, or federal policies (e.g., reservation system, land seizures).

1 mark: Demonstrates coherent reasoning and connects evidence to the overall argument.