AP Syllabus focus:

‘The U.S. government violated treaties, used military force against resistance, confined American Indians to reservations, and denied tribal sovereignty.’

Federal Indian policy in the late nineteenth century reflected escalating conflicts over land, sovereignty, and cultural survival as the United States expanded westward and imposed increasingly coercive control.

Federal Indian Policy after the Civil War

Federal Indian policy between 1865 and 1898 centered on the consolidation of American Indian communities under tighter federal authority. This period witnessed the systematic violation of treaty agreements, the deployment of military force to suppress resistance, and the development of a formal reservation system designed to relocate Indigenous nations while opening Western lands to settlers, miners, and railroads. These actions reshaped the political and cultural landscape of Native nations and reinforced U.S. sovereignty claims across the continent.

Treaty Violations and the Erosion of Sovereignty

Changing Federal Approaches

During the antebellum era, treaties functioned as diplomatic agreements recognizing tribes as sovereign nations. After the Civil War, U.S. policymakers increasingly rejected this framework. Congress ended treaty-making with Indigenous nations in 1871, signaling that the federal government viewed tribes as dependent populations rather than independent political entities. This shift accelerated the erosion of tribal sovereignty, even as earlier treaties theoretically remained binding.

Systematic Violations

Federal and territorial authorities routinely broke treaty commitments to secure access to land, minerals, and strategic routes. Important examples include:

The Black Hills seizure (1870s) after the discovery of gold, despite the region being guaranteed to the Lakota in the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868).

Encroachments on Nez Perce lands, prompting conflicts when the government attempted to force non-treaty bands onto smaller reservations.

Reduction of reservation boundaries through repeated congressional acts and executive orders, often without tribal consent.

Sovereignty: The authority of a nation or people to govern itself without external control.

The denial of sovereignty justified federal claims that Indigenous peoples needed supervision, paving the way for assimilationist policies and increased military intervention.

Military Force and Armed Resistance

The Army as an Instrument of Policy

Military force became central to enforcing federal authority in the West. The U.S. Army established forts, patrolled transportation routes, and intervened whenever Indigenous resistance threatened settler expansion or commercial interests. Officials argued that force was necessary to protect migrants and ensure the “orderly” development of the frontier.

Major Conflicts

Key confrontations illustrate how military action shaped federal policy:

The Red River War (1874–1875) sought to remove Comanche, Kiowa, and Southern Cheyenne from the southern Plains and confine them to reservations.

The Great Sioux War (1876–1877) followed Black Hills disputes and included the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which prompted intensified U.S. military campaigns.

The Nez Perce War (1877) resulted from forced relocation demands and culminated in a long pursuit across the Northwest.

The Wounded Knee Massacre (1890) marked a violent end to the Plains wars as the Army cracked down on the Ghost Dance movement.

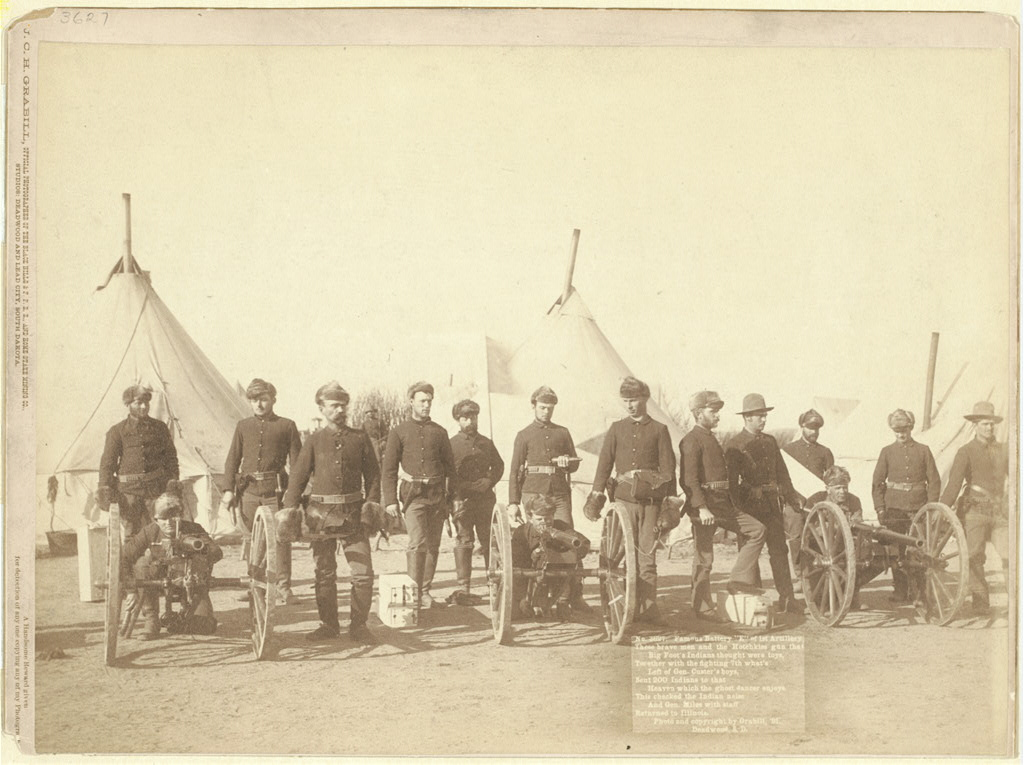

Group portrait of Battery “E” of the 1st U.S. Artillery, whose Hotchkiss guns were deployed against Lakota people at Wounded Knee in 1890. The soldiers stand in front of tents, emphasizing the militarized presence that enforced federal Indian policy in the late 19th century. This image extends beyond the syllabus by highlighting specific weaponry used at Wounded Knee, but it concretely visualizes how industrial-era firepower made resistance increasingly costly for Native nations. Source.

These conflicts demonstrated the willingness of the federal government to use overwhelming force to end Indigenous autonomy and secure land for U.S. settlement.

Establishing the Reservation System

Purposes and Structure

Reservations emerged as the centerpiece of federal policy, organized to confine tribes to specific territories under federal oversight.

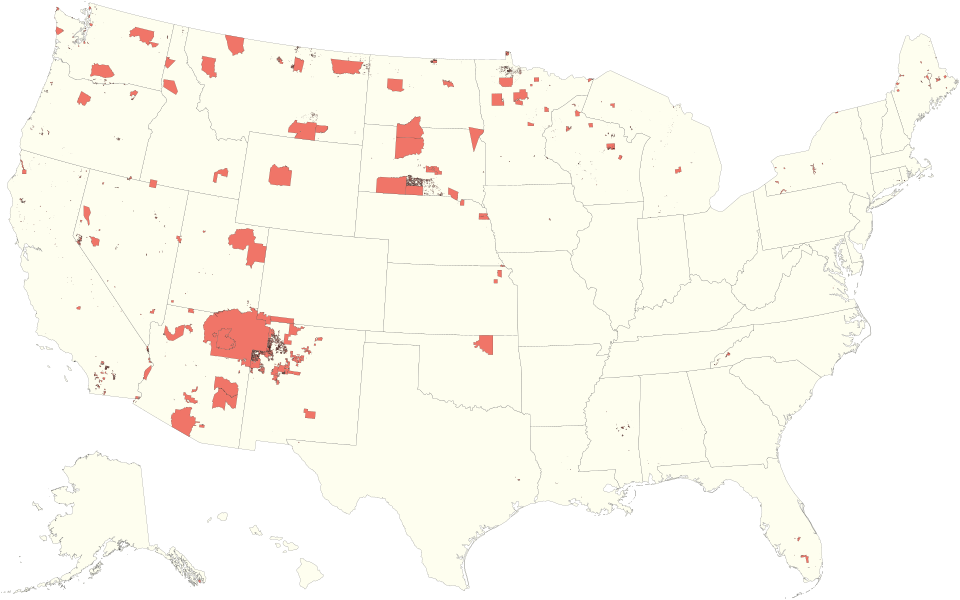

Map of Indian reservations and associated trust lands in the United States, highlighting how Native nations are confined to discrete, often isolated tracts of land. Although this is a modern map, it illustrates the long-term result of the 19th-century reservation policy discussed in the notes. Students should focus on how scattered and discontinuous these lands are, reflecting the fragmentation of tribal homelands over time. Source.

Their goals included:

Concentrating Indigenous populations for easier surveillance.

Opening remaining lands for white settlement, railroad construction, and resource extraction.

Facilitating cultural assimilation through regulation, education, and missionary activity.

Federal Administration

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) supervised reservations, often plagued by corruption, inadequate supplies, and harsh disciplinary practices. Indian agents wielded substantial power, distributing rations, enforcing rules, and reporting resistance to military authorities.

Living Conditions and Constraints

Reservation life severely restricted traditional economic systems such as hunting, seasonal migrations, and intertribal trade.

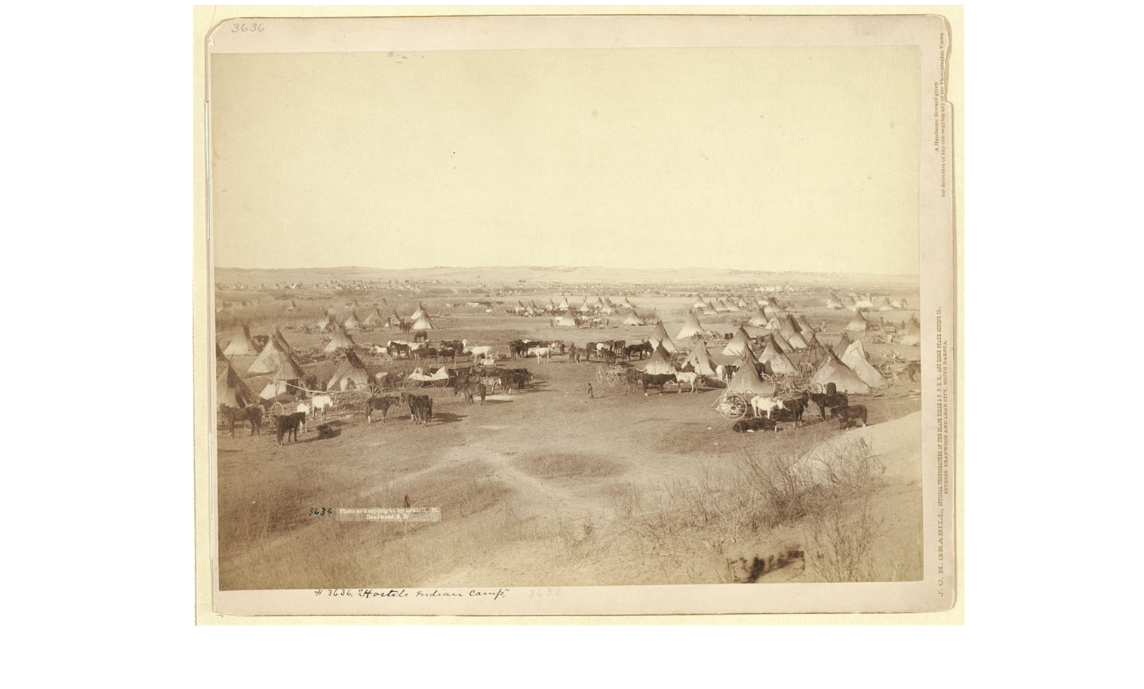

Bird’s-eye view of a Lakota camp near Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota, showing tipis, horses, and wagons grouped together under close observation. The scene illustrates how federal policy concentrated Native people in limited spaces rather than allowing broad seasonal migrations across the Plains. The hostile label on the original photograph reflects contemporary U.S. attitudes that treated Indigenous communities as threats even when simply encamped. Source.

Some key impacts included:

Dependence on government-issued rations.

Pressure to adopt sedentary farming despite environmental challenges.

Disruption of social structures and cultural practices.

Regulations limiting movement, political organization, and religious expression.

Assimilation: A process in which a dominant society pressures minority groups to adopt its cultural norms, values, and practices.

Reservation policies structured assimilation by separating Indigenous peoples from their homelands, weakening communal cohesion, and restricting spiritual traditions.

The Legal and Political Denial of Tribal Sovereignty

Federal Court Decisions

A series of court rulings reinforced the idea that tribes were “domestic dependent nations.” As a result, tribes retained limited internal authority but lacked full political independence. These decisions supported broad congressional power to alter agreements unilaterally.

Congressional and Administrative Policies

Congress increasingly legislated Indian affairs directly, culminating in measures like the Dawes Act of 1887, which divided communal reservation lands into individual allotments. Although allotment is covered more fully in other subsubtopics, its origins in federal assumptions about sovereignty and dependency began in the period addressed here.

Long-Term Implications

By denying sovereignty, violating treaties, and enforcing military control, the U.S. government aimed to integrate Indigenous peoples into an expanding national economy while erasing their political independence. The reservation system became both a physical and symbolic expression of these goals, shaping Indigenous life for generations.

FAQ

The 1871 decision meant Indigenous nations were no longer recognised as sovereign entities capable of negotiating formal diplomatic agreements. Instead, Congress assumed direct authority over Indian affairs.

This shifted power dramatically, allowing the government to alter land boundaries, impose policies, and manage reservations without tribal consent.

It also reinforced the idea that Native peoples were domestic dependants rather than independent political communities.

Many policymakers assumed that concentrating Indigenous peoples on defined tracts of land would prevent clashes over hunting grounds, migration routes, and settlement activity.

They argued that reservations would:

• Create physical separation between Native communities and incoming settlers.

• Allow the Army and the Bureau of Indian Affairs to monitor tribes more closely.

• Make it easier to deliver rations and enforce assimilation policies.

Indian agents had extensive authority, often exceeding what was typical for federal administrators elsewhere.

They controlled ration distribution, reported resistance to military commanders, enforced farming requirements, regulated movement, and approved or denied tribal leadership decisions.

Corruption was common, and mismanagement could lead to hunger, unrest, or federal military intervention.

When boundaries were broken, tribes were forced into smaller spaces or compelled to share reservations with groups they had long-standing disputes with.

This created:

• Competition for limited resources.

• Disruption of traditional alliances and rivalries.

• Increased dependence on federal mediation, further weakening sovereignty.

Army officials misinterpreted such movements as signs of impending rebellion rather than as religious or cultural responses to crisis.

Believing the frontier needed strict control, officers viewed mass gatherings and spiritual revivalism as indicators of potential coordinated resistance.

This fear contributed to escalated surveillance and ultimately violent interventions such as those leading to Wounded Knee.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify two ways in which the United States government restricted tribal sovereignty through its Indian policy in the late nineteenth century.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for each accurate and relevant way (up to 2 ways).

• 1 additional mark for brief elaboration of either point showing understanding of how sovereignty was limited.

Acceptable answers may include:

• Ending treaty-making in 1871 (1 mark).

• Unilaterally altering or breaking existing treaties (1 mark).

• Using military force to compel relocation or suppress resistance (1 mark).

• Confined tribes to reservations under federal authority (1 mark).

• Additional elaboration such as noting that tribes were treated as dependent populations or lost the ability to negotiate as sovereign nations (1 mark).

Maximum: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how federal violations of treaties and the use of military force contributed to the development and enforcement of the reservation system between 1865 and 1898.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1–2 marks for describing treaty violations (e.g., land seizures, unilateral reductions of reservation boundaries).

• 1–2 marks for describing the use of military force (e.g., suppression of resistance, conflicts such as the Great Sioux War or Wounded Knee).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how these actions contributed to the formation and enforcement of the reservation system (e.g., justification for confinement, federal authority, enabling westward expansion).

• Responses that coherently link causes and consequences may receive the top marks.

Indicative content:

• Treaty violations undermined Native sovereignty and removed legal protections of land, allowing the government to impose relocation.

• Military campaigns against resisting tribes demonstrated federal willingness to use force to secure land for settlers and enforce policy.

• These actions enabled the reservation system by concentrating tribes in restricted areas for surveillance and control, supporting the wider aims of westward expansion and assimilation.

Maximum: 6 marks.