AP Syllabus focus:

‘Despite assimilation policies, many American Indians preserved culture and tribal identity and pursued self-sustaining economic practices.’

American Indians faced intense assimilation pressures in the late nineteenth century, yet many communities adapted creatively, preserving cultural identity, resisting coercive policies, and forging new pathways for economic and social survival.

Indigenous Resilience Under Assimilation Pressures

Federal Assimilation Policies and Indigenous Responses

Late nineteenth-century federal Indian policy aimed to eradicate tribal sovereignty, replace communal landholding, and impose Euro-American cultural norms. These goals shaped a vast assimilation project that profoundly affected daily life in Native nations. The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 attempted to convert Indigenous peoples into individual landowners by dividing reservations into private allotments. Policymakers believed that breaking communal land tenure would accelerate cultural transformation and open “surplus” lands to white settlers.

Many Native communities responded with a blend of resistance, adaptation, and strategic engagement. Rather than passively accepting allotment or forced acculturation, tribes evaluated ways to preserve identity, protect land, and maintain continuity amid federal pressure. Some communities attempted to leverage the law to defend resources or avoid further displacement, while others opposed or evaded allotment programs entirely.

Cultural Preservation Despite Assimilation Efforts

Assimilationists expected Native children to abandon traditional languages and beliefs through boarding school systems, which removed children from their families and imposed strict linguistic and cultural rules.

Pupils at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School pose in uniform clothing before brick dormitories, illustrating the scale and regimentation of boarding school life. The photo reflects federal attempts to impose English-language instruction and cultural conformity. Architectural details in the setting extend beyond the syllabus focus but support understanding of institutional assimilation environments. Source.

Yet Indigenous youth often found ways to maintain connections to tribal identity through covert cultural practice, storytelling, and forming supportive peer networks. Families also worked to re-teach cultural knowledge upon students’ return, ensuring the endurance of core traditions.

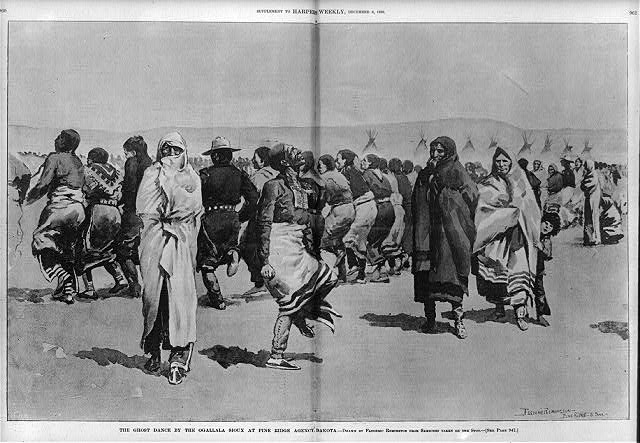

Syncretic religious movements, especially the Ghost Dance, reflected Indigenous attempts to sustain spiritual life in the face of oppression.

This 1890 illustration shows Oglala Lakota dancers performing the Ghost Dance, a syncretic movement expressing spiritual resilience amid dispossession. The circular formation conveys collective identity and hope. Background figures such as soldiers provide additional context beyond syllabus requirements but clarify federal fears surrounding the movement. Source.

Syncretism: The blending of different cultural, spiritual, or social traditions into a new, cohesive practice.

Maintaining seasonal ceremonies, kinship structures, and oral histories allowed tribes to safeguard identity even as federal agents attempted to suppress traditional customs.

Adaptation Through Economics and Community Strategies

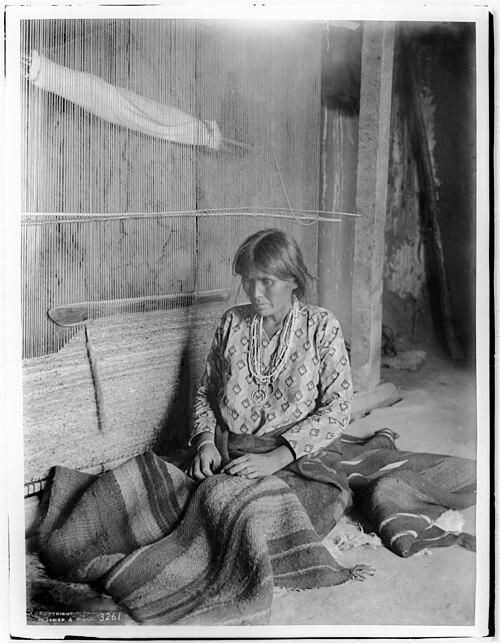

Indigenous people developed self-sustaining economic practices that blended traditional lifeways with opportunities emerging in the late nineteenth-century market economy.

A Navajo woman weaves at a traditional loom while completed blankets hang nearby, illustrating the continuity of craft-based economies under federal assimilation pressure. Weaving sustained cultural knowledge and supported economic independence. Elements of domestic setting shown exceed syllabus scope but deepen understanding of daily life and labor. Source.

Key adaptive economic approaches included:

Small-scale agriculture and ranching, which many tribes pursued to meet subsistence needs and reduce dependence on federal rations.

Participation in wage labor, including railroad construction, mining, military scouting, and seasonal agricultural work, enabling families to supplement limited reservation resources.

Traditional crafts production, such as basketry, beadwork, and pottery, which found growing markets among tourists and collectors, allowing cultural expression to support material survival.

These practices did not reflect assimilation into mainstream economic norms as much as they demonstrated resourcefulness in reshaping new systems to fit tribal needs.

Political and Legal Adaptation

Despite attempts to destroy tribal sovereignty, Native nations continued to assert political authority. Tribal councils met to resolve internal matters, maintain legal customs, and limit the reach of federal agents. Leaders protested treaty violations, petitioned Congress, and used the U.S. legal system to challenge federal policies.

Indigenous political resilience included:

Collective petitions defending treaty rights and land claims.

Intertribal diplomacy, strengthening alliances to resist encroachment.

Use of legal appeals, as in the landmark case Cherokee Nation v. Hitchcock (1902), demonstrating persistent efforts to protect community autonomy.

These actions revealed that tribes were not passive subjects of federal control but active participants shaping their own futures.

Education, Knowledge, and Selective Adaptation

While federal schooling aimed to eradicate Indigenous knowledge, many Native communities selectively embraced forms of education that could support tribal survival. Students learned English literacy, agricultural methods, or vocational skills that later aided political advocacy, resource management, and intertribal communication.

At the same time, elders ensured that traditional knowledge—ecological understanding, oral literature, and cultural teachings—remained central to identity formation. The coexistence of Western and Indigenous knowledge systems exemplified adaptation rather than cultural surrender.

Community Continuity and Identity Maintenance

Even under the most restrictive assimilation regimes, Indigenous peoples anchored identity through family networks, communal rituals, and landscape-based memory. Reservation boundaries could not erase long-standing relationships to land, which continued to structure spiritual practice and social organization.

Cultural resilience appeared in:

Continuity of kinship obligations, which reinforced community cohesion.

Preservation of Indigenous languages, maintained in homes and ceremonial spaces.

Cultural transmission, as elders taught children history, songs, and values outside the reach of federal schools.

These actions ensured that the foundation of tribal life persisted despite policies designed to eliminate it.

Adaptation as Resistance

Indigenous resilience in the late nineteenth century was not merely survival but a form of resistance. By preserving culture, adapting economic strategies, and reasserting political authority, Native communities contested the logic of assimilation and forged pathways for future sovereignty movements. Their responses revealed the limits of federal power and the enduring strength of tribal identity across the United States.

FAQ

Kinship networks provided a framework for political coordination, resource sharing, and collective decision making, enabling communities to negotiate or subtly resist federal demands.

These networks also helped distribute labour and care responsibilities, ensuring that cultural teachings, land knowledge, and social norms persisted across generations even when families were fragmented by boarding schools.

Spiritual leaders often reframed older traditions in ways less visible to federal agents, integrating elements of Christianity to avoid punishment while retaining core spiritual meanings.

Some teachings shifted into domestic or familial spaces rather than public ceremonies, helping protect rituals from surveillance.

Women frequently acted as cultural anchors, maintaining language, domestic crafts, and foodways that federal agents viewed as less politically threatening.

Men engaged in seasonal or wage labour that expanded economic choices and reduced reliance on federal rations, offering families greater autonomy.

Together, gendered roles created a complementary framework for cultural continuity.

Intertribal alliances allowed communities to exchange strategies for navigating allotment, resist aggressive land policies, and support displaced individuals.

These alliances also facilitated shared ceremonial gatherings and cultural exchange, strengthening morale and reinforcing broader Indigenous identity beyond individual nations.

Artisans adapted traditional motifs to new materials and markets, allowing cultural symbolism to persist even within commercial contexts.

Some crafts encoded historical memory and political messages, enabling art to serve both economic and cultural functions.

In many communities, artistic production became a way to teach younger generations cultural meaning without attracting federal scrutiny.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which American Indian communities preserved their cultural identity despite late nineteenth-century federal assimilation policies.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

• Identifies a valid example of cultural preservation (e.g., maintaining Indigenous languages, continuing ceremonial practices, sustaining oral traditions).

2 marks:

• Provides a brief explanation of how the example preserved cultural identity (e.g., language maintenance kept tribal identity intact even within boarding schools).

3 marks:

• Offers a clear, historically grounded explanation linking the example directly to federal assimilation pressures and demonstrating how it resisted or mitigated those pressures.

(4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which Indigenous economic adaptation in the late nineteenth century represented a form of resistance to federal assimilation policies. Use specific historical evidence to support your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

• Describes at least one economic adaptation (e.g., traditional crafts, small-scale agriculture, wage labour) and explains how it supported community survival.

• Shows basic understanding of federal assimilation aims (e.g., allotment, reservation dependency).

5 marks:

• Uses specific evidence to link economic adaptation to active resistance (e.g., weaving maintained cultural knowledge while generating independent income; wage labour reduced reliance on federal rations).

• Demonstrates awareness of Indigenous agency in reshaping imposed economic conditions.

6 marks:

• Provides a well-reasoned assessment of the extent of resistance, considering both limits and strengths of economic adaptation under assimilation pressures.

• Integrates precise historical detail and shows clear analytical judgement about how adaptation served as both economic necessity and cultural resilience.