AP Syllabus focus:

‘Southern leaders promoted a “New South” through industrialization, but sharecropping and tenant farming remained the South’s primary economic activity.’

The “New South” vision promoted industrial growth and modernization after the Civil War, yet most Southerners continued to depend on agricultural systems that limited economic transformation.

The Postwar Quest for a “New South”

Southern boosters—politicians, journalists, and business leaders—argued that the former Confederate states required a dramatic economic shift. They envisioned a diversified economy grounded in modern industry, railroad expansion, and urban development that would move the South away from its prewar dependence on plantation agriculture. Despite this optimistic rhetoric, the postwar South experienced a difficult economic transition marked by entrenched poverty and limited industrial investment.

Ideology Behind the New South Vision

Advocates such as Henry Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, portrayed industrialization as the key to regional recovery. They promoted a future marked by economic self-sufficiency, competitive manufacturing, and stronger integration with national markets. This ideological campaign emphasized:

Attracting Northern capital to build factories, mills, and railroads

Diversifying agricultural and industrial output

Developing cities to rival northern manufacturing centers

Reforming labor systems to increase efficiency

Supporters insisted that industrial capitalism would replace the old plantation elite with a modern commercial class. Yet structural realities prevented this vision from becoming widespread.

Portrait of Henry W. Grady, an influential Atlanta journalist and leading spokesman for the “New South” vision. Grady championed railroad expansion, textile growth, and diversified industry as keys to Southern recovery. His rhetoric contrasted sharply with the region’s persistent agricultural dependence. Source.

Limited Industrial Growth in Practice

Industrial development did occur—textile mills expanded, the Birmingham iron and steel industry grew, and railroad mileage increased dramatically. However, these enterprises were geographically concentrated and insufficient to transform the broader economy. Investment depended heavily on Northern financiers, leaving Southern industrialization shaped by outside interests. This meant profits often flowed out of the region rather than circulating locally.

Interior of Magnolia Cotton Mills in Mississippi, with spinning machinery stretching across the room and children working among the frames. The photo illustrates the rise of Southern textile industries promoted by New South boosters, while highlighting the exploitative labor conditions that accompanied limited industrial growth. Its 1911 date extends slightly beyond the period but accurately reflects established Gilded Age industrial patterns. Source.

Constraints on Industrial Expansion

Several barriers slowed industrial growth and preserved agricultural dominance:

Chronic capital shortages, which forced reliance on Northern investors

Low consumer purchasing power in a predominantly impoverished region

A poorly educated workforce, limiting labor flexibility

Limited urbanization, preventing the emergence of robust industrial markets

Persistent racial hierarchy, discouraging equitable economic participation

Because these obstacles remained unresolved, industrialization could not offset the enduring power of agricultural labor systems.

Sharecropping and Tenant Farming as Dominant Labor Systems

Following the Civil War, sharecropping and tenant farming became the primary means of agricultural production across the South. Landowners, lacking enslaved labor and capital, divided land into small plots that families worked in exchange for a share of the crop. This system quickly spread among formerly enslaved African Americans and poor white farmers.

Sharecropping: A labor arrangement in which workers farm a landowner’s plot in exchange for a portion of the harvested crop.

Because landlords controlled supplies, credit, and crop sales, sharecroppers remained trapped in cycles of debt peonage, making economic mobility rare. Tenant farming, a related system in which workers rented land for cash or a larger crop share, offered slightly more autonomy but still imposed severe financial pressures.

Normal sentence between definition blocks.

Debt Peonage: A condition in which workers cannot leave their jobs because accumulated debts bind them to landowners or merchants.

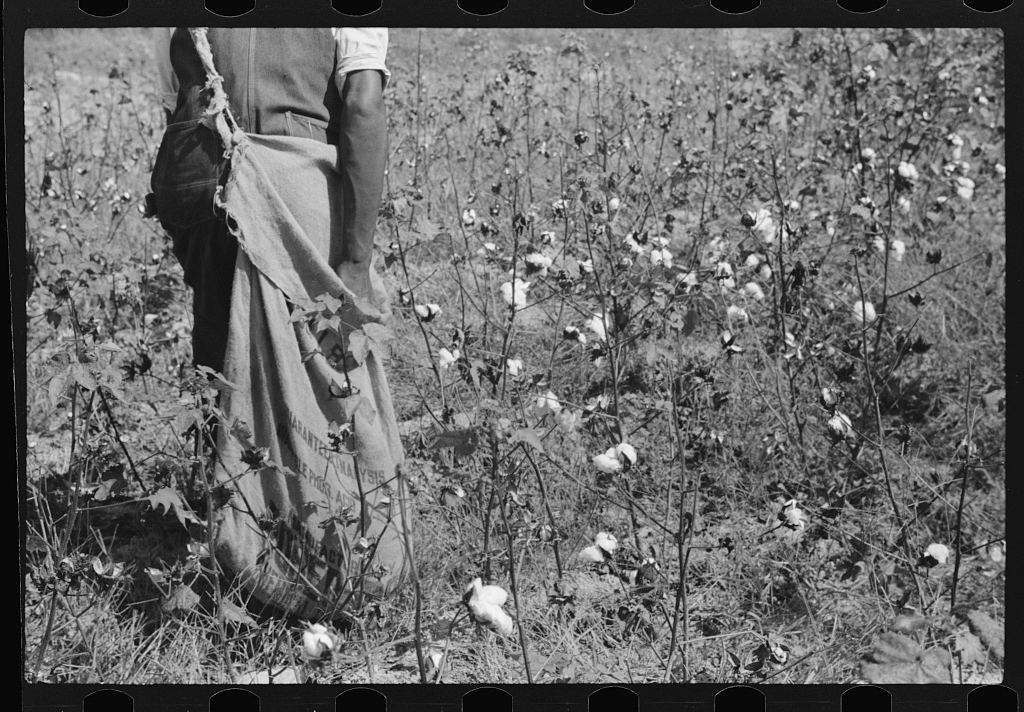

African American sharecropper picking cotton in North Carolina in 1939. The image reflects the labor-intensive agricultural system that dominated the South long after emancipation, illustrating the persistence of poverty and limited mobility under sharecropping. Although taken later than the 1865–1898 period, it accurately represents the economic patterns established in the New South era. Source.

These systems tied the Southern economy to cotton cultivation and discouraged innovation or diversification. They also reinforced racial and class inequalities that paralleled the region’s political structures.

Agricultural Dependence and Its Economic Consequences

With most Southerners living in rural areas, agricultural production shaped regional life more strongly than industrial ventures. The dominance of cotton meant:

Vulnerability to global price fluctuations, which could devastate farmers’ incomes

Reliance on credit from local merchants, often at exorbitant interest rates

Slow adoption of mechanization, unlike the rapidly industrializing Midwest

The South’s dependence on cotton depressed wages, limited urban growth, and hindered the development of a consumer base that could support large-scale industry. Industrial leaders promoted the image of progress, but the economic reality for ordinary Southerners remained defined by subsistence labor and precarious finances.

Regional Inequality and the Persistence of the Old Order

Despite claims of modernization, power remained concentrated among a small group of landowners, merchants, and industrial investors. These elites benefitted from the existing agricultural system, which provided inexpensive labor and minimized political challenges from impoverished workers. Racial discrimination further structured opportunity, constraining African Americans and ensuring the continuation of social systems resembling those of the prewar era.

Outcomes of the Limited New South Transformation

Industrialization occurred but remained secondary to agriculture

Manufacturing centers emerged but did not rival Northern cities

Most Southerners continued in low-wage, low-mobility agricultural work

Wealth inequalities persisted across racial and class lines

The region remained the poorest in the nation through the late nineteenth century

The contrast between the New South rhetoric and its economic reality reveals a region attempting modernization while constrained by entrenched labor systems, limited capital, and enduring social hierarchies.

FAQ

Boosters used speeches, newspaper campaigns, and investment fairs to present the South as a region open to business, emphasising cheap labour, abundant natural resources, and low taxes.

They also promoted the idea that racial stability and political conservatism would protect investors’ interests, making the region appear economically dependable.

Southern farmers faced chronic debt, which forced them to prioritise high-demand cash crops like cotton rather than experiment with diversified farming.

Merchants and lenders further reinforced cotton dependence by offering credit only to those growing profitable staple crops, creating a cycle that discouraged agricultural innovation.

Railroad expansion was portrayed as the backbone of regional modernisation, enabling industrial growth and connecting Southern towns to national markets.

However, many lines were controlled by Northern companies, limiting local economic autonomy and channelling profits out of the South.

The region relied heavily on low-wage, often landless workers whose skills were rooted in agriculture rather than manufacturing.

This labour pool made industries possible but not necessarily competitive, since productivity lagged behind northern factories requiring more specialised, mechanised skills.

Cities grew around rail hubs and mill towns, but most remained small due to persistent rural poverty and the dominance of agricultural employment.

Urban centres struggled to attract a diverse workforce, and limited municipal investment slowed improvements in housing, infrastructure, and public services needed to sustain larger populations.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why Southern industrialisation remained limited during the period associated with the “New South” vision after the Civil War.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award marks for the following:

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., lack of capital, dominance of sharecropping, limited infrastructure, reliance on Northern investment).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation of how this reason limited industrialisation.

3 marks: Gives a developed explanation that clearly links the factor to the broader economic continuity in the South.

(4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1865–1898, assess the extent to which the “New South” vision succeeded in transforming the Southern economy.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks for the following:

1–2 marks: Describes features of the “New South” vision or briefly outlines some economic changes.

3–4 marks: Provides accurate, relevant examples (e.g., growth of textile mills, Birmingham steel industry, continued dependence on cotton agriculture) and explains how they support an argument about the success or failure of the vision.

5–6 marks: Constructs a balanced assessment that recognises both aspirations and limitations, uses specific evidence, and clearly evaluates the overall extent of economic transformation.