AP Syllabus focus:

‘Internal and international migration expanded the industrial workforce and made it more diverse in the late nineteenth century.’

Industrial growth after the Civil War drew millions of newcomers into expanding urban and industrial centers, creating a larger and more diverse workforce that reshaped economic, social, and cultural life.

Expanding Labor Needs in an Industrializing Nation

The rapid expansion of factories, railroads, and large-scale enterprises in the late nineteenth century created an unprecedented demand for labor. As mechanization increased output, industrial employers sought workers who could operate machines, endure repetitive tasks, and sustain continuous production cycles. This demand pushed businesses to recruit labor from both within the United States and across the world, driving population movement on a massive scale.

Internal Migration and Workforce Growth

Internal migration contributed significantly to workforce expansion, as individuals and families moved toward industrializing regions for new opportunities.

Rural-to-urban migration accelerated as agricultural overproduction, falling crop prices, and economic volatility pushed many Americans off the land.

Southern Black migrants, facing persistent discrimination, limited economic mobility, and racial violence, moved into Northern and Midwestern cities where industrial work offered comparatively higher wages and the possibility of community formation.

Western migrants relocated toward rail hubs and mining centers as certain resource-based industries began incorporating wage labor and mechanized processes.

The movement of Americans into industrial centers diversified the workforce by region, background, and skill level, reshaping urban demographics and working-class culture.

International Migration: Sources and Patterns

Industrial employers also relied heavily on international migrants, whose arrival dramatically altered labor markets. These migrants came from global regions undergoing their own economic and political transformations.

Southern and Eastern Europeans—including Italians, Poles, Russians, and Austro-Hungarians—arrived in increasingly large numbers, fleeing poverty, land shortages, and political repression.

Asian migrants, particularly Chinese and later Japanese laborers, contributed substantially to railroad construction, mining, and service-sector work in the West.

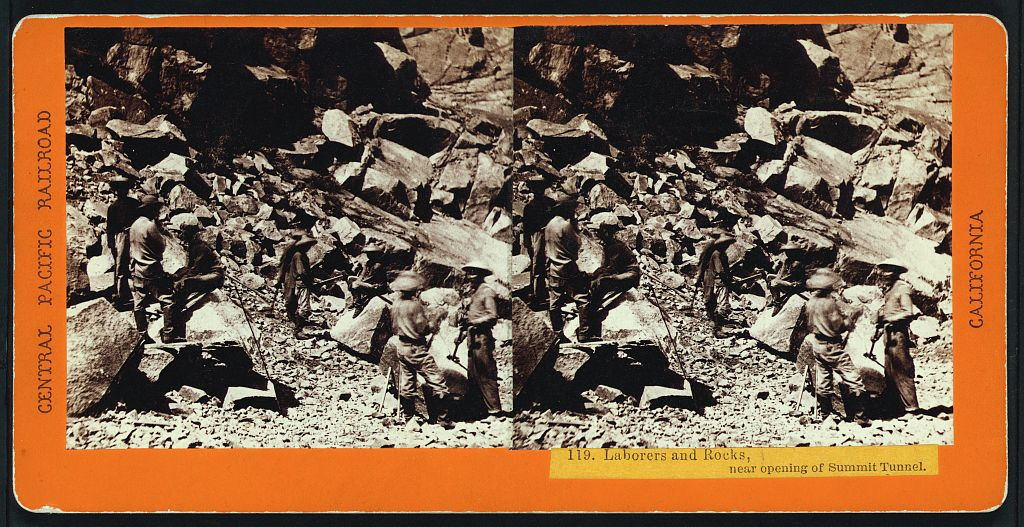

Chinese laborers work among blasted rock near the Summit Tunnel of the Central Pacific Railroad in the Sierra Nevada during the 1860s. Their low-paid but dangerous work helped complete the first transcontinental rail line, tying Western resources and towns to national industrial markets. Although focused on railroad construction rather than later urban jobs, the image directly represents Asian migrants’ central role in Western labor. Source.

Canadian and Latin American migrants crossed land borders for seasonal, industrial, and agricultural labor, serving as flexible components of the growing labor force.

When historians refer to the New Immigration, they describe the wave of migrants from Southern and Eastern Europe after the 1880s.

New Immigration: A late nineteenth-century migration wave dominated by Southern and Eastern European arrivals who differed culturally, linguistically, and religiously from earlier Northern and Western European migrants.

A sentence here reiterates how definitions support understanding of broader labor trends.

Why Migration Increased Workforce Diversity

Industrial growth intersected with global and domestic pressures that encouraged population movements. Several push-and-pull factors shaped the workforce:

Economic Push Factors

Agricultural crises, including soil exhaustion and declining global crop prices

Mechanization reducing agricultural labor demand

European economic stagnation and land scarcity

Debt burdens and rural poverty in multiple world regions

Economic Pull Factors

Availability of factory jobs, particularly in textiles, steel, oil, and food processing

Wage labor opportunities in construction, railroads, and mining

Growing urban centers that promised upward mobility

Expanding transportation networks that reduced travel time and cost

Employers actively encouraged these migrations by offering incentives or recruiting directly through labor agents. Such proactive strategies expanded the labor pool and allowed firms to maintain low wages and high production levels.

Changing Urban and Workplace Environments

The growth of a diverse labor force fundamentally altered American cities and workplaces.

Ethnic neighborhoods emerged as migrants settled near people who shared language, religion, and cultural practices.

Boardinghouses and tenements became common living arrangements, especially among recent arrivals who needed affordable housing.

Industrial discipline shaped worker experiences, introducing strict schedules, close supervision, and mechanized routines unfamiliar to many newcomers.

Cities transformed into mosaics of overlapping communities, each participating in the broader industrial economy while maintaining cultural distinctiveness.

Tensions and Interactions Within a Diverse Workforce

Workplace diversity fostered cooperation but also competition.

Wage competition between different groups sometimes intensified ethnic and racial animosities, particularly when employers used certain workers as strikebreakers.

Racial and ethnic hierarchies shaped access to skilled positions; native-born workers often gained supervisory roles, while immigrants and racial minorities filled lower-wage jobs.

Labor organizing efforts had to navigate linguistic barriers and cultural differences, complicating unionization but also inspiring more inclusive organizing strategies.

Despite tensions, shared working conditions—long hours, dangerous factories, and insecure wages—encouraged workers from diverse backgrounds to recognize common struggles.

Broader Social and Cultural Implications

The influx of internal and international migrants helped create the dynamic, heterogeneous society characteristic of Gilded Age America.

Migrants reshaped urban culture through new languages, traditions, foods, and religious practices.

Public debates intensified over assimilation, Americanization, and national identity as the workforce diversified.

Policymakers and social reformers grappled with how to respond to rapidly changing demographics.

Industrial migration thus served as both an economic necessity and a catalyst for profound cultural transformation in the late nineteenth century.

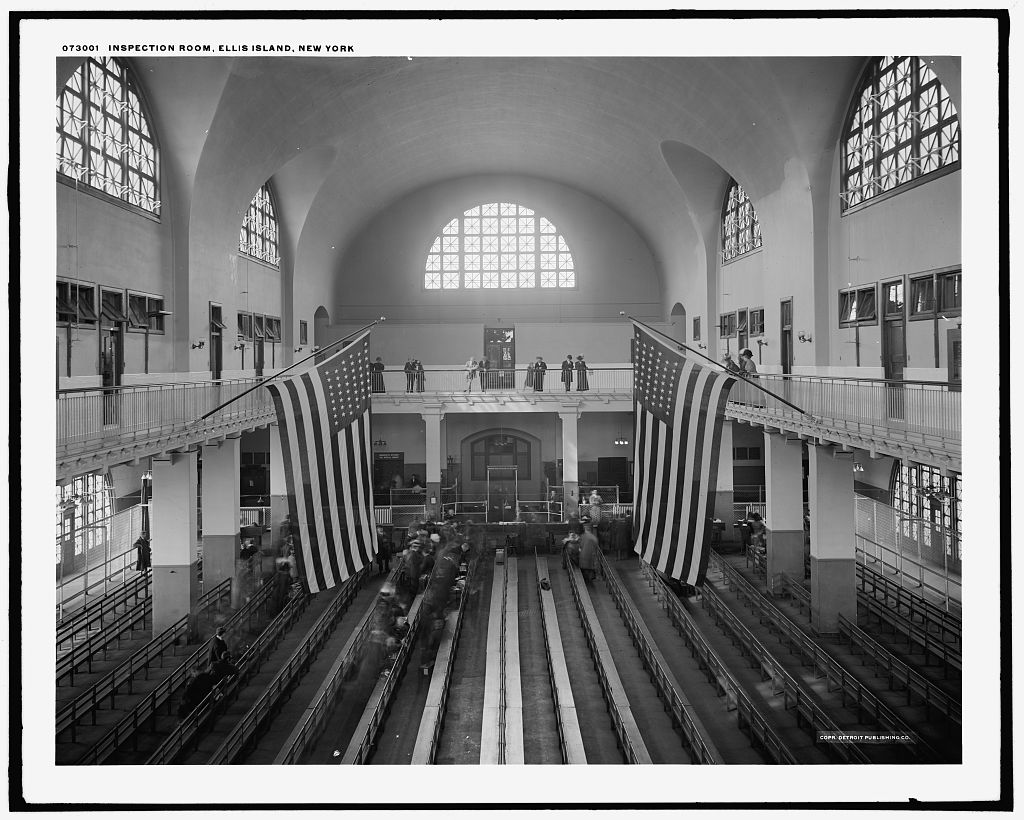

Immigrants line up in the inspection room at Ellis Island, the primary federal receiving station for European arrivals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The image highlights how mass immigration was organized through large, regimented processing spaces before newcomers could move on to jobs in factories and cities. The photograph slightly postdates 1898 but reflects procedures already shaping the Gilded Age workforce. Source.

Immigrants crowd the bow of the S.S. Canopic as it arrives in Boston in 1920, one of many ships that carried European migrants to U.S. industrial ports. The scene illustrates how steamship technology sustained large-scale transatlantic migration into northern cities. Although dated just after 1898, it visually represents migration processes already well

FAQ

Recruitment networks often relied on chain migration, where earlier migrants wrote home describing job opportunities and living conditions, encouraging relatives and neighbours to follow.

Steamship companies, labour agents, and shipping posters in European port cities promoted inexpensive passage and emphasised plentiful industrial jobs in American cities.

Some employers paid intermediaries to recruit workers directly, especially for railroads, mining, and low-wage factory work.

A significant number of immigrants—particularly Southern and Eastern Europeans—engaged in circular or return migration, travelling to the United States for seasonal or short-term industrial work and then going home.

This practice created a fluctuating labour pool that employers could tap during periods of high demand, especially in construction, steel production, and mining.

Return migrants often used their earnings to purchase land, start businesses, or improve family livelihoods in their home countries.

Crowded tenements near factories allowed migrants to live within walking distance of workplaces, reducing transport costs and enabling long working hours.

Shared housing arrangements, such as boarding houses and ethnic lodgings, helped newcomers pool resources and adapt more easily to urban environments.

These housing patterns reinforced community networks that supported job searching, childcare, and mutual aid.

Language diversity often made communication within factories difficult, especially in industries relying on large migrant workforces such as steel and textiles.

Employers sometimes used linguistic divisions to discourage collective action, placing workers from different language groups in separate teams.

When unions began organising across ethnic lines, they developed multilingual pamphlets and meetings to overcome communication challenges.

Internal migrants—particularly African Americans and rural whites—were more likely to speak English and therefore accessed a broader range of semi-skilled jobs.

International migrants often entered the lowest-paid, most physically demanding roles, though some groups formed ethnic niches in specific industries such as mining, garment work, or food processing.

Over time, as communities stabilised, both internal and international migrants gradually moved into skilled trades, small business ownership, or supervisory positions, though racial discrimination limited these paths unevenly.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one specific pull factor that encouraged international migrants to move to the United States during the late nineteenth century and explain how it contributed to the growth of a more diverse industrial workforce.

Question 1

• 1 mark for correctly identifying a pull factor, such as higher wages, factory job availability, or improved transport links.

• 1 mark for explaining how the pull factor encouraged migrants to relocate to the United States.

• 1 mark for explicitly linking the migration to the growth of a more diverse industrial workforce (e.g., migrants supplying labour to factories, railroads, or urban industries).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how both internal and international migration contributed to the expansion and diversification of the industrial workforce in the late nineteenth century. In your answer, refer to at least two distinct migrant groups and discuss how economic conditions shaped their movement and employment patte

Question 2

• 1–2 marks for describing internal migration (e.g., rural Americans or African Americans moving to industrial cities).

• 1–2 marks for describing international migration (e.g., Southern/Eastern Europeans, Chinese labourers).

• 1 mark for explaining the economic conditions that pushed or pulled these groups (e.g., poverty, mechanisation, wage opportunities).

• 1 mark for linking these migrations to workforce expansion and increased diversity (e.g., linguistic, cultural, racial, and occupational variety in industrial centres).

High-level responses (6 marks) will:

• Provide clear explanations of both internal and international migration.

• Use specific examples of migrant groups.

• Explicitly connect these patterns to changes in the industrial workforce.