AP Syllabus focus:

‘Growing cities attracted immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe and drew African American migrants seeking jobs and to escape poverty, persecution, and limited mobility.’

Urban America in the late nineteenth century exerted a powerful pull on diverse populations, offering industrial jobs, economic mobility, and escape from political, social, and economic hardship across the United States and abroad.

Expanding Urban Economies and the Attraction of Industrial Employment

Cities grew rapidly after the Civil War as industrial capitalism reshaped the national economy. Urban centers such as Chicago, New York, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland became hubs of factory production, drawing large numbers of workers with promises of steady wages and mass employment opportunities.

Industrial Work as a Pull Factor

The expansion of mass production and mechanized systems generated unprecedented labor demand. Factories, steel mills, meatpacking plants, and textile industries required constant staffing, attracting both domestic and international migrants.

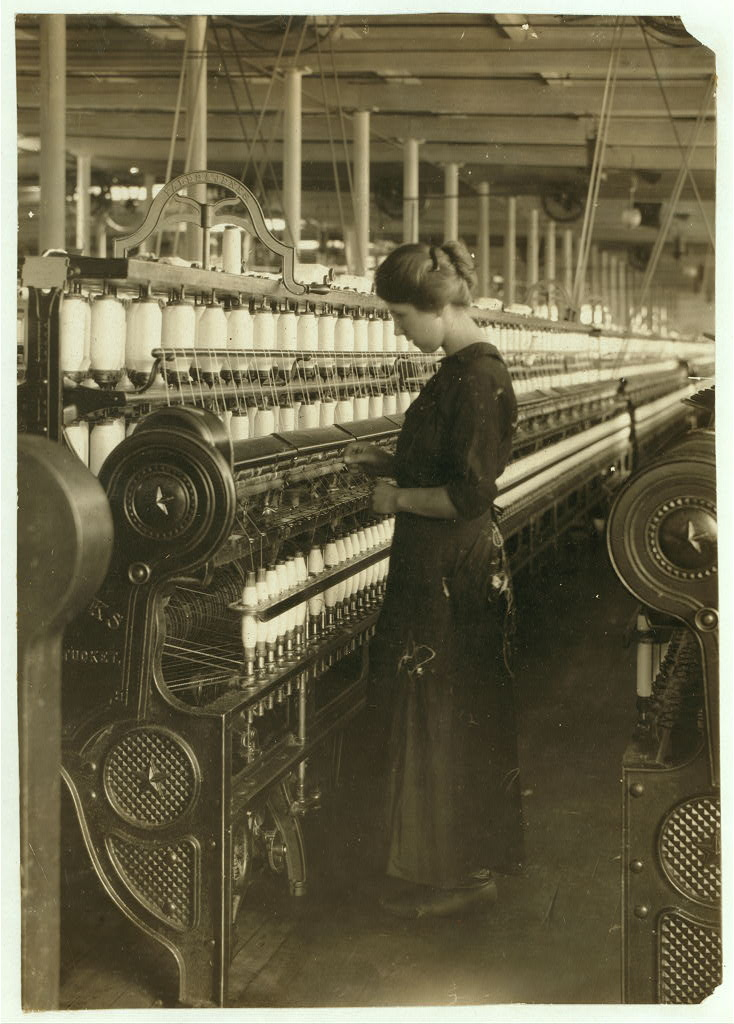

A fourteen-year-old spinner stands beside rows of spindles in a cotton mill, illustrating how industrial employment created steady—if demanding—work that drew migrants to urban industrial centers. The inclusion of a child worker adds detail beyond the syllabus but highlights the intensity of labor demand in textile factories. Source.

Recruitment strategies by major employers brought workers from rural America and abroad.

Low-skill, high-demand jobs allowed recent arrivals to quickly enter the workforce.

Wage labor provided more predictable income compared to farming or seasonal rural work.

New Opportunities for African American Migrants

African Americans, primarily from the South, relocated to cities in search of economic security and increased autonomy. They were drawn by

higher urban wages,

escape from sharecropping debt cycles,

and avoidance of racial persecution that persisted after Reconstruction.

Sharecropping: A labor system in which tenants farmed land owned by others in exchange for a share of the crops, often creating long-term debt and dependency.

African Americans hoped urban life would provide mobility unavailable under the restrictive Jim Crow framework developing across the South.

Immigration Waves and the Urban Labor Force

The late nineteenth century witnessed massive migration from southern and eastern Europe, as well as continued arrivals from China and other parts of Asia.

Immigrants walk toward inspection facilities at Ellis Island, reflecting how U.S. port cities served as gateways to growing urban labor markets. Although from 1902, the image captures the broader migration patterns that accelerated during the late nineteenth century. Source.

Motivations for International Migrants

International migrants were influenced by both push and pull factors.

Push factors included political turmoil, religious persecution—particularly for Jewish migrants—economic stagnation, and agricultural crises.

Pull factors centered on the promise of urban employment, rising industrial wages, and family or community networks that eased transition.

Many newcomers entered rapidly expanding labor sectors:

construction work,

garment manufacturing,

mining-related urban industries,

and service jobs supporting growing urban populations.

Escaping Poverty and Hardship

Economic hardship across rural America and abroad meant that cities symbolized opportunity for self-improvement. The shift to wage labor represented a significant life change, especially for those burdened by stagnant rural economies, famine conditions, or exploitative labor arrangements.

Limited Mobility and Barriers at Home

Rural populations—both native-born and immigrant—faced declining agricultural prices, limited access to land, and restricted educational or economic pathways. In many countries, rigid social structures limited mobility, making the United States’ urban centers particularly appealing.

Economic mobility: The ability of individuals or families to improve their economic status through wages, education, or changes in occupation.

Urban migration was viewed as an avenue for achieving upward mobility not readily available elsewhere.

Expanding Infrastructure and the Ease of Movement

Transportation and communication developments accelerated migration into cities.

Railroads connected rural regions and facilitated long-distance moves.

Steamship travel reduced international voyage time and cost.

Telegraphs and postal systems allowed migrants to communicate with relatives, lowering uncertainty about conditions in the United States.

These innovations supported continuous migration flows that reinforced the labor supply essential to industrial growth.

Social Networks and Community Anchors

Urban migration was rarely an isolated decision. Many migrants relied on chain migration, in which early arrivals from a region or community encouraged others to follow.

Immigrant neighborhoods provided language support, cultural familiarity, and assistance navigating labor markets.

African American migrants often settled near existing Black communities, where churches and mutual aid societies eased adjustment.

These community anchors reduced risk and strengthened the urban pull for new arrivals.

The Appeal of Urban Modernity

Cities offered attractions unavailable in rural areas, including

public schools,

electricity and modern utilities,

mass transit systems,

and diverse commercial goods.

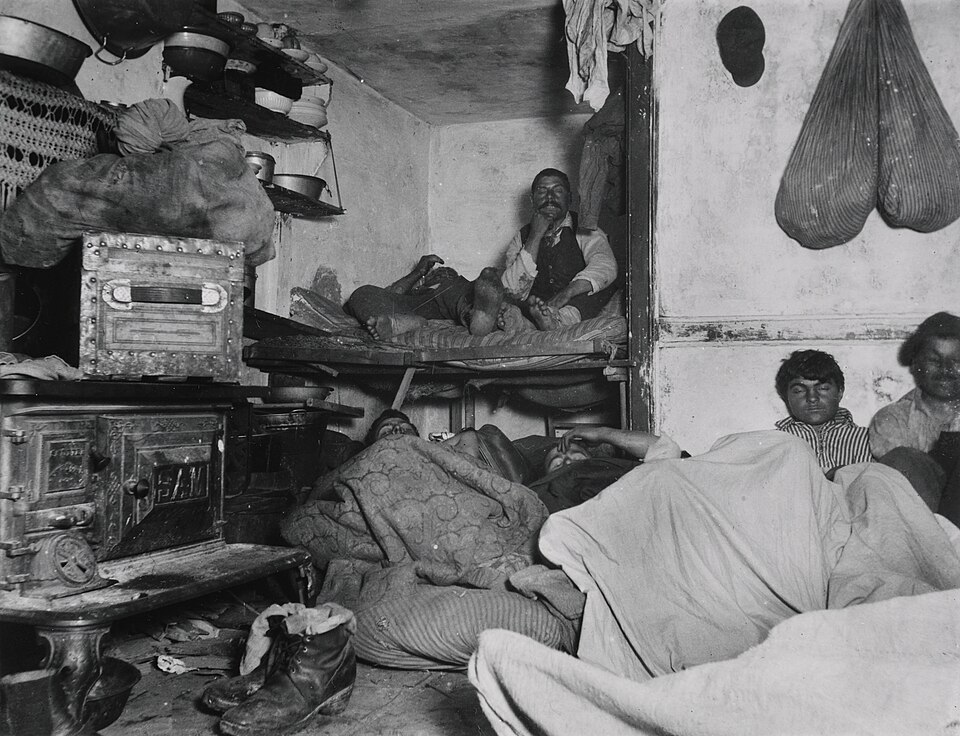

Such amenities contributed to a perception of progress and possibility. Even though living conditions could be harsh—crowded tenements, pollution, and labor exploitation—migrants weighed these challenges against the lack of opportunity in their places of origin.

Riis’s photograph depicts an overcrowded tenement interior, demonstrating the harsh living environments many migrants encountered despite the draw of urban employment. The image contains additional muckraking context not required by the syllabus but clearly illustrates conditions in Gilded Age working-class housing. Source.

Urban Migration and the Reshaping of American Society

By the end of the nineteenth century, migration into cities had transformed the national demographic landscape. Burgeoning urban centers became engines of economic output, cultural exchange, and social change. The diverse groups drawn by factories, jobs, and the desire to escape hardship reshaped the workforce and redefined the character of American urban life in the Gilded Age.

FAQ

Steamship companies played an active role in shaping migration flows by lowering fares, improving travel conditions, and increasing the regularity of transatlantic routes.

They marketed aggressively in rural Europe and Asia, making urban-bound migration more accessible and predictable.

Because ships commonly arrived at major ports such as New York and Boston, migrants tended to remain in or near these cities, reinforcing urban concentration.

In addition to large industrial employers, migrants often entered sectors that supported urban growth, including:

• streetcar operation and maintenance

• dock and warehousing labour

• food-processing trades outside major factories

• domestic service and laundry work

• small-scale retail and workshop manufacturing

These roles were plentiful in expanding cities and required minimal formal training.

Urban jobs offered more consistent wages, making it easier for migrants to send remittances to families abroad.

Reliable income streams encouraged permanent or semi-permanent city residence, as rural or agricultural work provided less stable earnings.

Remittances also reinforced chain migration, with relatives following those who had successfully secured urban employment.

Yes. Port cities such as New York and Boston tended to receive the largest influx of newcomers, resulting in dense ethnic neighbourhoods close to docks and factories.

Inland centres like Chicago or Cleveland drew migrants who had either travelled onwards from ports or who were recruited directly by companies seeking labour.

These inland cities often developed more occupationally diverse migrant communities due to their mixed industrial economies.

Community institutions eased adaptation by offering:

• language classes

• small loans or emergency assistance

• employment referrals

• cultural events and festivals

They also provided social stability in crowded, unfamiliar environments, helping migrants navigate housing, work disputes, and local politics.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one major pull factor that encouraged international migrants to settle in American cities during the late nineteenth century, and briefly explain why it attracted them.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a valid pull factor (e.g., availability of factory jobs, higher wages, access to modern urban services).

1 additional mark: Provides a brief explanation of why this factor attracted migrants (e.g., factory work offered steady wage labour compared to unstable agricultural work).

1 additional mark: Explanation clearly connects the factor to urban growth or industrial expansion (e.g., industrial cities required constant staffing, drawing newcomers into expanding labour markets).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how both economic opportunity and conditions in migrants’ places of origin contributed to increased urban migration in the United States during the late nineteenth century. In your answer, refer to at least two different migrant groups.

Question 2

1 mark: Identifies at least one economic pull factor (such as industrial jobs, mass production industries, wage labour).

1 mark: Explains why these opportunities were appealing to migrants, linking to the broader context of urban industrial growth.

1 mark: Identifies at least one push factor from places of origin (e.g., poverty, agricultural decline, persecution, limited mobility).

1 mark: Explains how these push factors motivated migration.

1 mark: Uses at least two specific migrant groups discussed in the syllabus (e.g., southern and eastern European immigrants, Asian migrants, African Americans from the South).

1 mark: Provides coherent explanation of how both push and pull factors worked together to increase migration to American cities.