AP Syllabus focus:

‘Urban neighborhoods organized by ethnicity, race, and class created new cultural opportunities and shaped daily life in American cities.’

Late-nineteenth-century migration fueled the growth of ethnic neighborhoods, where shared traditions, institutions, and social networks created distinctive urban cultures that shaped community identity and daily life.

Ethnic Neighborhood Formation

Large numbers of immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe, along with African American migrants from the rural South, settled in rapidly expanding cities. These migrants often clustered with others who shared similar languages, religions, or cultural practices, creating concentrated districts that reflected the diversity of the Gilded Age.

Geographic and Social Concentration

Specific sections of cities developed reputations as cultural enclaves. Immigrants typically gravitated to familiar faces, trusted networks, and walkable areas close to industrial jobs.

Chain migration—a process in which earlier arrivals helped relatives or villagers follow—reinforced neighborhood clustering.

Shared hiring networks and ethnic labor brokers connected newcomers to factories, docks, and service work.

Religious landmarks such as churches, synagogues, and temples anchored community life and offered familiarity amid rapid urbanization.

Chain Migration: A migration pattern in which earlier migrants assist friends or relatives in relocating to the same destination community.

Living conditions in these enclaves varied widely. While some areas supported thriving businesses and institutions, many others experienced overcrowding, poor sanitation, and high rents due to rapid urban growth and limited urban planning.

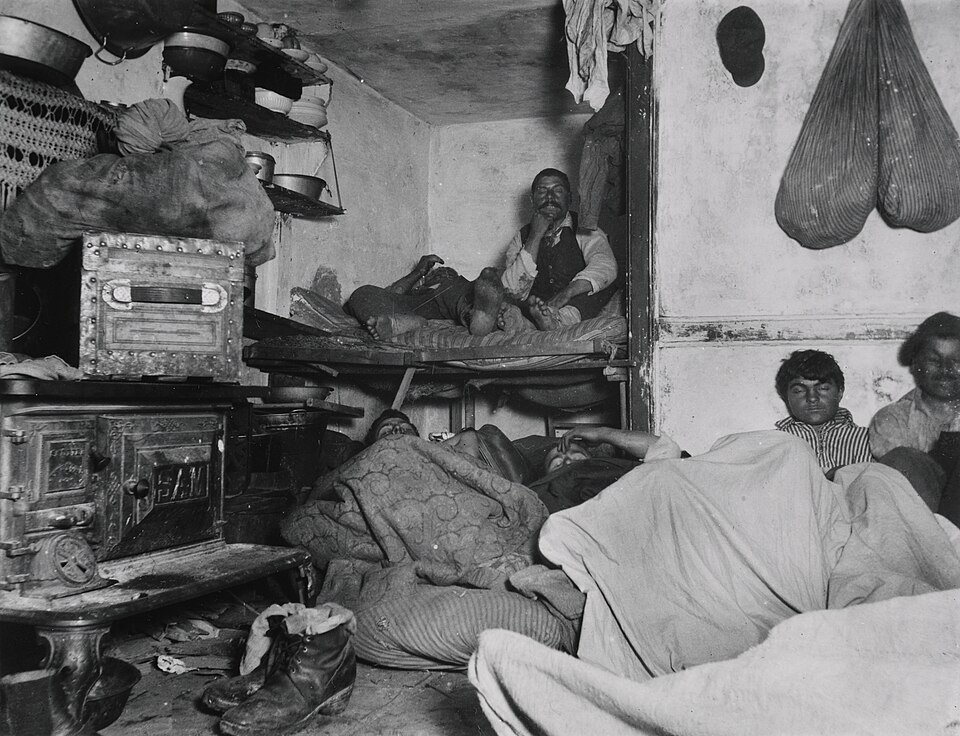

Jacob Riis’s photograph depicts men crowded into a small tenement room, illustrating the cramped and unsanitary housing conditions many workers and immigrants faced. The image emphasizes the pressures of limited space and low wages within dense ethnic neighborhoods. Although Riis used the image for broader reform advocacy, it is shown here to demonstrate typical Gilded Age tenement living conditions. Source.

Cultural Maintenance and Adaptation

Ethnic neighborhoods served as vital spaces in which migrants preserved cultural traditions while adapting to the demands of industrial America. Residents blended old-country customs with new urban experiences, creating hybrid cultural forms.

Institutions and Community Support

Neighborhood institutions played essential roles in shaping daily life and enabling migrants to navigate the pressures of assimilation.

Mutual-aid societies offered financial assistance during illness, unemployment, or emergencies.

Newspapers in languages such as Yiddish, Italian, Chinese, and Polish provided news, political commentary, and cultural continuity.

Ethnic schools and social clubs helped younger generations balance American expectations with inherited traditions.

Local shops, markets, and theaters reinforced cultural preferences and safeguarded familiar tastes and practices.

These institutions gave migrants opportunities to assert autonomy in cities where discrimination, economic insecurity, and political exclusion were common.

Urban Culture and Social Dynamics

The rise of ethnic neighborhoods fostered new urban cultures that transformed city life across the United States. These cultures shaped entertainment, work, politics, and social relationships.

New Cultural Forms

Immigrant communities reshaped the cultural landscape of cities.

Music, festivals, parades, and religious holidays filled streets with sounds and colors that distinguished one neighborhood from another.

Ethnic cuisines, from Italian bakeries to Jewish delicatessens, became defining features of urban experience.

Theaters and performance halls served as gathering places for storytelling, political debate, and community celebration.

These cultural expressions allowed migrants to sustain communal identity even as they engaged with broader American society.

Interactions with Other Urban Populations

Although neighborhoods were often dominated by a single ethnicity, cities remained dynamic and diverse spaces.

Proximity sometimes encouraged cultural exchange, such as shared marketplaces and entertainment venues.

Tensions also emerged from competition for jobs, housing, and political influence, especially in crowded districts.

African American migrants developed their own urban cultures, contributing to musical innovation, religious life, and new forms of activism within racially segregated areas.

Neighborhood boundaries could shift as populations changed, signaling the evolving nature of urban identity.

Class, Labor, and Urban Experience

Class divisions shaped ethnic neighborhoods as deeply as race and nationality. Even within a single ethnic group, wealthier families sought better housing or suburban areas, while poorer workers lived in tenements near factories.

Housing, Work, and Daily Pressures

Industrial labor structured much of neighborhood life.

Long working hours in factories or sweatshops limited leisure and increased reliance on local institutions.

Tenement housing, with its cramped rooms and shared facilities, reinforced collective living patterns.

Street life—from marketplaces to informal economies—provided additional income and strengthened community ties.

“Bandits’ Roost” captures the dense social world of alleyways in immigrant tenement districts, where residents gathered, worked, and interacted in shared outdoor spaces. The photograph highlights how limited indoor space pushed daily life into courtyards and alleys, reinforcing collective neighborhood identity. While associated with period concerns about crime, its primary relevance here is its depiction of the built environment of ethnic urban communities. Source.

These pressures affected cultural adaptation. Working-class migrants were more likely to rely on neighborhood networks for survival, while middle-class residents often had greater opportunities for upward mobility and schooling.

Political Influence and Urban Power

Ethnic neighborhoods contributed to political change in the Gilded Age. Although many migrants lacked immediate access to political rights, urban machines recognized their importance.

Civic Participation and Political Machines

Political machines provided jobs, housing assistance, and legal aid to win loyalty.

In return, community leaders mobilized neighborhood votes, making immigrant enclaves crucial to municipal elections.

Ethnic newspapers and clubs became vehicles for political education and debate.

These relationships helped migrants influence urban governance, even when broader nativist pressures sought to restrict their social and political participation.

Transformation of Urban Life

As ethnic neighborhoods flourished, they reshaped American urban culture more broadly. Their languages, customs, foods, religious celebrations, and artistic traditions contributed to a more diverse national identity. Cities became mosaics of overlapping cultures that reflected the complexities of migration, labor, and community formation during the Gilded Age.

FAQ

Landlords often rented to specific immigrant groups because it reduced vacancy risk; word-of-mouth ensured steady demand within tight-knit communities.

They also subdivided housing to maximise profit, reinforcing clustering as only the poorest newcomers accepted overcrowded tenement conditions.

In some districts, property owners informally tolerated culturally distinct commercial activity—such as street vending—which further shaped neighbourhood identity.

Informal economies allowed immigrants with limited English or formal training to earn income quickly.

Common roles included street vending, home-based piecework, laundry work, and food preparation.

These activities:

supplemented low industrial wages

provided flexible work for women and children

strengthened social networks by linking work with community spaces

Women frequently became cultural anchors by maintaining language, food traditions, and religious practices at home.

They also formed sewing circles, church groups, and aid clubs that fostered mutual support.

Meanwhile, men often joined fraternal societies that provided insurance, employment leads, and political connections, reflecting differing social expectations by gender.

Children navigated dual expectations: their family’s cultural traditions and the Americanising influence of schools and workplaces.

Many acted as language brokers for parents, translating documents and negotiating with employers or shopkeepers.

Playgrounds, alleyways, and schoolyards became spaces where hybrid cultural identities emerged through shared games, slang, and friendships across ethnic lines.

Longevity depended on factors such as economic mobility, discrimination, and access to improved housing.

Neighbourhoods persisted when residents lacked financial means to relocate or faced hostile reception elsewhere.

In contrast, groups experiencing upward mobility moved to better districts or suburbs, leading to gradual dispersal and cultural blending beyond the original enclave.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which ethnic neighbourhoods shaped daily life in American cities during the Gilded Age. Explain why this development occurred.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid feature of ethnic neighbourhoods (e.g., creation of culturally distinctive street markets, establishment of ethnic institutions such as churches or mutual-aid societies, preservation of language and customs).

1 mark for explaining why this feature developed (e.g., immigrants clustered for support, familiarity, shared language, and employment networks).

1 mark for connecting the development to wider patterns of migration or urban growth (e.g., rapid immigration, overcrowding, limited housing options, reliance on community networks).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which ethnic neighbourhoods in the late nineteenth century both preserved cultural traditions and facilitated adaptation to urban industrial life.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for a clear thesis or judgement addressing the extent of both preservation and adaptation.

1–2 marks for describing how ethnic neighbourhoods preserved cultural traditions (e.g., festivals, religious institutions, ethnic newspapers, language use, traditional foods).

1–2 marks for explaining how these neighbourhoods also facilitated adaptation (e.g., providing job networks, mutual-aid societies, political mobilisation, gradual cultural blending).

1 mark for discussing balance or limitation (e.g., overcrowding, poverty, discrimination, pressures of assimilation influencing how effectively communities preserved culture).

Answers gaining full marks should demonstrate a balanced argument with accurate evidence and clear explanation.