AP Syllabus focus:

‘Imperialists justified expansion using economic opportunity, racial theories, competition with European empires, and the belief that the western frontier was “closed.”’

American imperialists at the turn of the twentieth century supported overseas expansion because they believed economic opportunity, strategic necessity, racial ideology, and global competition required a more assertive U.S. international presence.

Economic Motivations for Expansion

Industrialization transformed the United States into a powerful manufacturing nation seeking new markets, materials, and investment opportunities overseas. As domestic markets became increasingly saturated, advocates argued that national prosperity required the acquisition of foreign markets and access to global resources.

The Search for New Markets

Many business leaders feared economic downturn if American industrial output continued to outpace domestic consumption. Overseas expansion was framed as a solution, and policymakers such as Senator Albert Beveridge promoted the idea that the United States needed access to Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific to maintain economic growth.

U.S. companies expected imperialism to expand consumers for American finished goods.

Direct control of territories was believed to stabilize trade by limiting European interference.

Investment opportunities abroad promised high returns for American financiers.

Markets: Geographic regions or populations where goods can be sold, often pursued by industrial powers to sustain economic expansion.

American leaders frequently connected these goals to national economic security, arguing that stagnation at home made international expansion essential for preventing future depressions.

The Frontier Thesis and the “Closed” Frontier

The belief that the American frontier had shaped the nation’s development influenced imperialist thinking. After the Census Bureau declared the frontier “closed” in 1890, many feared the loss of the space that had traditionally provided opportunity and democratic vitality.

Frederick Jackson Turner’s Influence

Turner argued that the frontier fostered independence, innovation, and social mobility. Imperialists adapted his ideas, claiming that pursuing frontiers abroad would continue this national tradition.

Overseas territories were treated as new frontiers for American enterprise.

Expansion was framed as a patriotic continuation of westward growth.

Foreign land acquisition was justified as necessary for social and economic progress.

This ideological connection between earlier continental expansion and overseas empire helped normalize imperialism for many Americans who saw it as the next step in national evolution.

Racial Theories and Cultural Hierarchies

Imperialism drew support from Social Darwinism, a doctrine applying evolutionary concepts to human societies. Supporters claimed that stronger nations naturally dominated weaker ones and that this hierarchy reflected biological and cultural superiority.

Social Darwinism: The belief that human societies compete in a struggle for survival, with stronger nations destined to rule weaker ones.

Proponents such as Josiah Strong argued that Anglo-Saxon Americans had a duty to “civilize” and Christianize other populations.

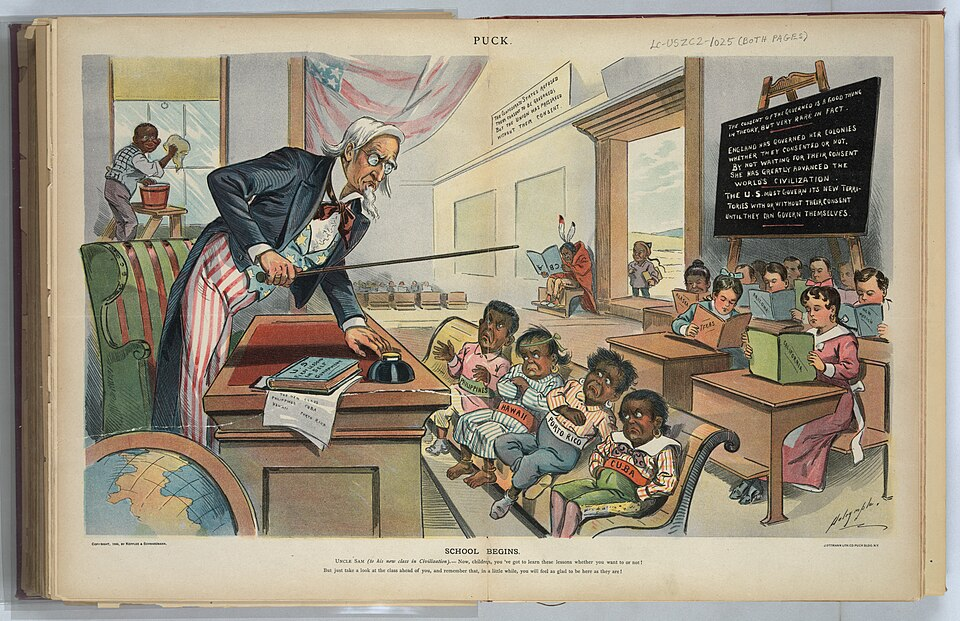

This cartoon shows Uncle Sam instructing newly acquired territories depicted as students, illustrating the racialized belief that nonwhite peoples required U.S. guidance and “civilization.” It also includes additional contextual elements such as older “states” observing from the back, offering visual depth beyond the AP syllabus focus. Source.

The Civilizing Mission

Imperialists blended religious and cultural arguments with strategic policy:

Missionaries sought to spread Christianity and Western education.

Politicians framed colonial rule as benevolent uplift for “less advanced” peoples.

Racial hierarchy provided ideological grounding for paternalistic governance.

These ideas reinforced public support by depicting empire as humanitarian rather than exploitative.

International Competition and Strategic Concerns

By the late nineteenth century, European powers were rapidly expanding global empires. Many Americans feared that without similar efforts, the United States would fall behind economically and diplomatically.

Imperial Rivalry

Nations such as Britain, Germany, and France dominated Africa and Asia.

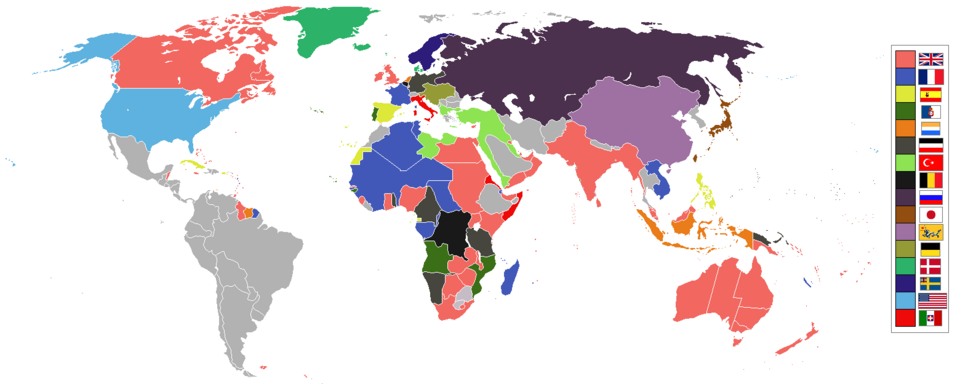

This map depicts the major imperial powers and their colonies in 1898, illustrating the intense global competition that shaped American fears of being left behind. It includes extensive detail on European colonial holdings not explicitly required by the AP syllabus but helpful for visualizing the broader imperial landscape. Source.

American imperialists believed participation in this global competition was necessary for maintaining great-power status.

A larger empire promised naval bases for the expanding U.S. fleet.

Control of key ports ensured access to Asian trade, especially in China.

Holding overseas territories was viewed as essential for national prestige.

The writings of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, who argued that naval power determined national greatness, significantly shaped these views. Mahan emphasized the need for coaling stations, island possessions, and a modern steel navy to protect American commerce and assert influence.

Naval power: A nation’s military strength at sea, viewed as central to protecting trade routes and projecting national influence in international affairs.

Mahan’s ideas encouraged policymakers to pursue territories such as Hawaii, the Philippines, and Caribbean islands as strategic assets in a rising American empire.

Strategic Positioning and Hemispheric Influence

Imperialists also drew on the Monroe Doctrine, which warned European powers against intervention in the Western Hemisphere. Expanding U.S. control in the Caribbean and Central America was framed as both defensive and necessary for safeguarding American interests.

Hemispheric Leadership

Expansion was portrayed as stabilizing the region against European threats.

Canal routes, especially across Panama, were central to long-term strategic planning.

A strong presence in the Pacific and Caribbean reinforced America’s emerging global role.

Imperialists believed these actions secured national security, supported economic expansion, and established the United States as a modern power capable of shaping international outcomes.

FAQ

Many leading industrialists and bankers actively lobbied politicians to support territorial acquisition, arguing that economic downturns could be avoided by securing overseas markets.

Their influence appeared through:

Funding pro-expansion publications

Advising policymakers on trade routes and investment opportunities

Supporting naval expansion to protect commercial interests

Business groups often framed expansion not only as profitable but as essential for national stability in an increasingly global economy.

Many expansionists argued that acquiring new territories would channel internal social tensions outward. As industrialisation intensified class conflict and labour unrest, some policymakers believed that new markets and resources would alleviate economic pressures at home.

They also viewed imperial ventures as unifying national projects capable of reducing regional and political divisions by promoting shared patriotic purpose.

Missionary groups circulated letters, reports, and public lectures describing overseas populations as vulnerable or oppressed, appealing to moral duty rather than economic interest.

They often worked closely with politicians by:

Supplying information about regions targeted for expansion

Advocating for protection of converts

Framing U.S. presence as benevolent rather than strategic

These narratives helped normalise imperialism for middle-class Americans who viewed mission work as humane.

Newspapers used sensational stories and dramatic imagery to frame foreign conflicts and territories as exciting opportunities for American involvement. This style of reporting made overseas expansion appear urgent and morally justified.

Editors such as William Randolph Hearst promoted:

Emotional coverage of international crises

Portrayals of rival empires threatening U.S. interests

Narratives that cast expansion as a defence of freedom

Although not official policy, press influence helped build mass support for imperialist action.

Naval strategists argued that the United States required a network of island bases to refuel and repair modern steel warships, which had limited operating range without coaling stations.

They believed island control would:

Protect merchant shipping

Enable rapid deployment during conflict

Establish U.S. presence along major trade routes

This strategic logic helped justify acquiring locations such as Hawaii, Guam, and parts of the Caribbean as stepping stones to wider influence.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one reason why American imperialists in the late nineteenth century believed overseas expansion was necessary.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for correctly identifying a reason (e.g., economic opportunity, racial theories, global competition, belief the frontier had closed).

1 mark for a clear explanation of how this reason encouraged expansion.

1 mark for contextual accuracy linking the reason to late nineteenth-century developments.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how economic and ideological factors combined to shape American support for overseas imperial expansion between 1890 and 1900.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying at least one economic factor (e.g., desire for new markets, access to raw materials, investment opportunities).

1 mark for explaining how this economic factor motivated imperial expansion.

1 mark for identifying at least one ideological factor (e.g., Social Darwinism, the civilising mission, nationalism, the frontier thesis).

1 mark for explaining how this ideological factor motivated expansion.

1 mark for showing how economic and ideological motives interacted or reinforced each other.

1 mark for accurate historical context (e.g., industrial growth, global imperial competition, debates about national power).