AP Syllabus focus:

‘Despite Wilson’s role in postwar negotiations, the Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles or join the League of Nations.’

The Senate’s rejection of the Treaty of Versailles and League of Nations revealed deep political divisions, conflicting visions of internationalism, and enduring debates about constitutional authority and national interests.

Wilson at Versailles and the Postwar Vision

President Woodrow Wilson arrived at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 determined to shape the peace settlement according to his Fourteen Points, which emphasized self-determination, open diplomacy, and mechanisms to prevent future conflict. Wilson’s most ambitious proposal—the League of Nations, an international organization designed to maintain peace through collective security—became the centerpiece of the Treaty of Versailles, even though many of his other goals were compromised during negotiations with Britain, France, and Italy.

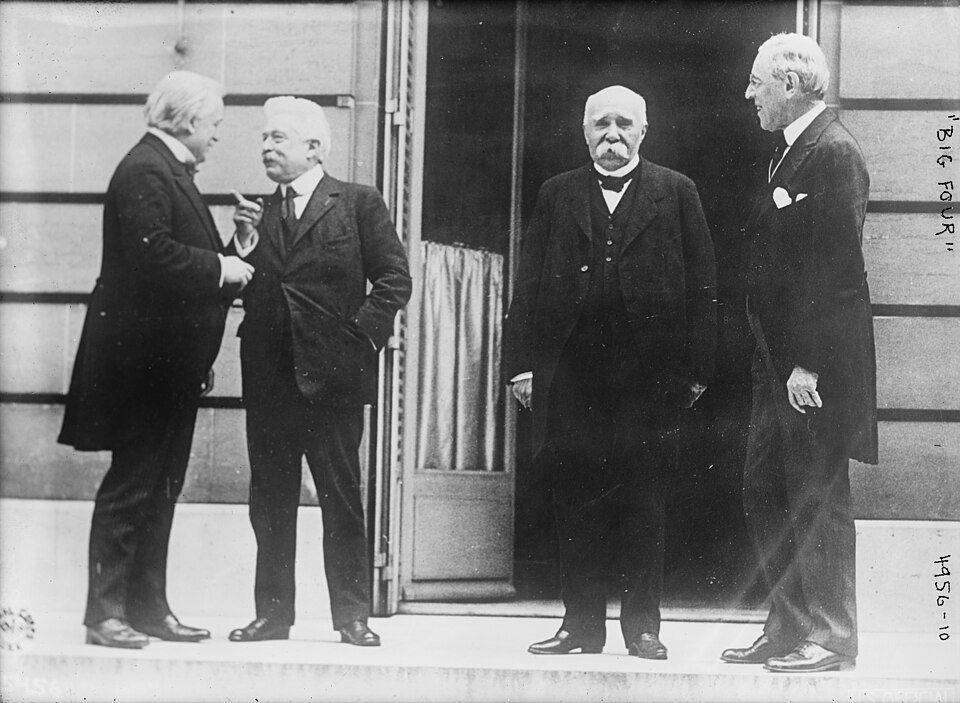

Photograph of the “Big Four” at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, showing the central diplomatic figures shaping the Treaty of Versailles. The image visually reinforces Wilson’s key role among the Allied leaders during treaty negotiations. Although it includes additional contextual detail not directly covered in the syllabus, it accurately depicts the setting in which the League of Nations covenant emerged. Source.

Key Terms in Wilson’s Vision

Collective Security: A diplomatic principle in which participating nations agree that an attack on one member constitutes a threat to all, requiring a unified response.

Wilson’s reliance on collective security, especially in Article X of the League Covenant, intensified concerns among many senators who feared that the United States would be obligated to defend other nations without congressional approval.

The Constitutional Stakes: Treaty Power and Senate Authority

Under the U.S. Constitution, the president negotiates treaties, but they must be ratified by a two-thirds vote in the Senate. Wilson’s failure to include leading Republicans—especially Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee—during treaty negotiations proved politically costly. Lodge and other Republicans argued that the president had sidelined them from vital decisions that would shape American foreign policy.

Senate Factions and Their Motivations

Senators fell into three broad groups as they considered the Treaty of Versailles:

Reservationists (led by Lodge): Willing to ratify the treaty with specific conditions or amendments, especially limiting obligations under Article X.

Irreconcilables: A small group of senators who opposed U.S. membership in the League of Nations under any circumstances because they believed it threatened national sovereignty.

Wilson Democrats: Loyal supporters of the president who generally rejected changes to the treaty, insisting on honoring the negotiated agreement.

Sovereignty: A nation’s independent authority to govern itself without external control or coercion.

These divisions shaped the contentious process of Senate deliberation, as each faction interpreted the League’s commitments differently.

Article X and the Debate over American Obligations

At the core of the Senate’s opposition was Article X, which called on League members to preserve the territorial integrity and political independence of all states within the organization.

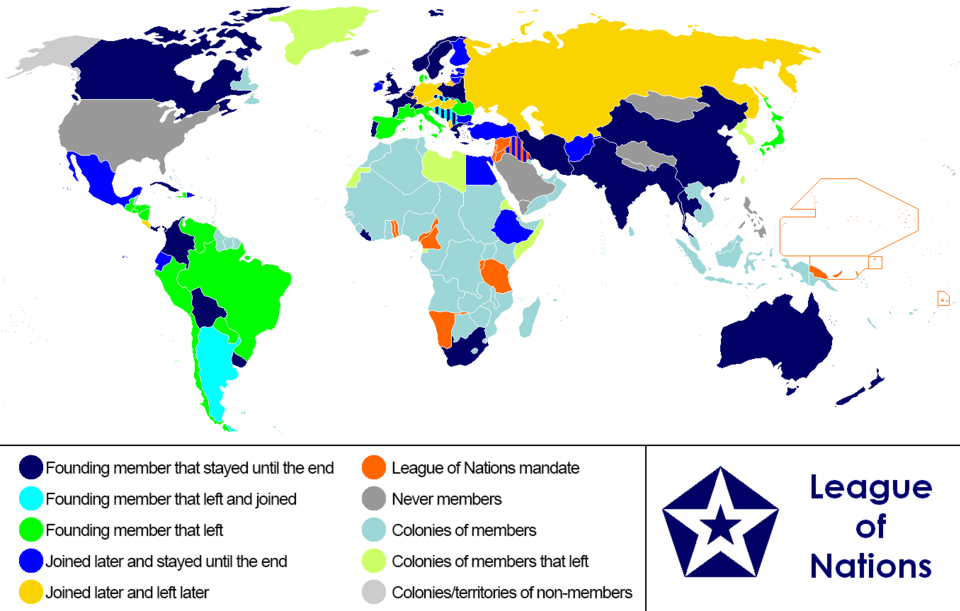

An anachronous world map illustrating the global membership of the League of Nations from 1920–1945. Its color-coding shows the organization’s broad reach and clarifies why American participation—or absence—carried geopolitical weight. Some map categories extend beyond syllabus requirements but help contextualize the League’s scale. Source.

Critics argued that this provision could compel the United States to enter foreign conflicts without the constitutional requirement of congressional approval for war declarations.

Major Concerns Raised by Opponents

The League could undermine U.S. control over its own foreign policy.

Collective security commitments might drag the nation into distant disputes.

The peace settlement failed to align fully with Wilson’s idealism, especially regarding self-determination.

The treaty’s punitive terms toward Germany risked future instability rather than lasting peace.

Between these objections, the debate raised enduring questions about the balance between international cooperation and national autonomy.

Political Conflict, Health Crises, and Public Opinion

Wilson attempted to win public support through a nationwide speaking tour in 1919, arguing that the League of Nations was essential to preventing future wars. However, the president suffered a debilitating stroke that left him unable to negotiate effectively with Senate leaders. His incapacitation hardened political positions: Wilson refused to accept Lodge’s reservations, and many Democrats in the Senate followed his lead by voting against a modified treaty that might otherwise have passed.

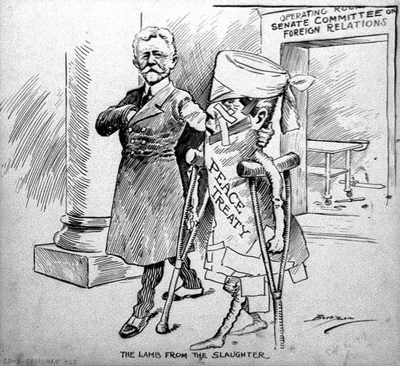

Clifford Berryman’s cartoon portrays Senator Henry Cabot Lodge guiding a wounded “peace treaty” covered in labeled reservations. The image captures the political struggle between Lodge’s faction and Wilson over altering the Treaty of Versailles. Symbolic elements not covered in the syllabus appear in the drawing but reinforce the tension surrounding Senate ratification. Source.

Public opinion was divided. Some Americans embraced Wilson’s idealism and saw the League as a moral step forward, while others supported the Senate’s caution or favored a return to isolationist traditions that had shaped U.S. policy in the nineteenth century.

Isolationism: A foreign policy stance advocating minimal involvement in international alliances, conflicts, or political commitments.

The failure to reconcile competing visions ultimately doomed the treaty.

Defeat of the Treaty and Its Global Implications

The Senate voted on the Treaty of Versailles twice—once with Lodge’s reservations and once without any alterations. Neither vote reached the necessary two-thirds approval. As a result, the United States never joined the League of Nations and instead concluded a separate peace with Germany in 1921.

Consequences of Senate Rejection

The League of Nations lacked participation from the world’s emerging economic and military power, weakening its ability to enforce collective security.

The decision signaled ongoing domestic debates about America’s proper role in global affairs—a tension that persisted into the 1930s.

The rejection highlighted the constitutional limits on presidential authority in foreign policy, reaffirming the Senate’s critical role in treaty ratification.

U.S. foreign policy entered a period of selective international engagement, balancing unilateral actions with avoidance of formal entangling alliances.

By refusing to ratify the Treaty of Versailles or join the League of Nations, the Senate reshaped the trajectory of American diplomacy in the interwar period, reinforcing skepticism toward international commitments and influencing global politics on the eve of World War II.

FAQ

Reservationists believed the United States could join the League of Nations if safeguards were added to protect congressional authority. Their amendments aimed to ensure that no military commitments could occur without explicit congressional approval.

They argued that altering the treaty, rather than discarding it, balanced international cooperation with constitutional responsibility. This approach allowed supporters to appear internationally engaged while maintaining domestic political control.

Wilson’s belief in moral leadership led him to treat the treaty as an idealistic mission rather than a negotiable political agreement. His unwillingness to consult key Republican leaders before attending the Paris Peace Conference alienated potential allies.

Additionally, his public appeals portrayed treaty critics as unpatriotic, which further hardened Senate opposition. This style transformed political disagreements into personal and ideological battles.

Certain progressives feared the League might entangle the United States in imperial or colonial disputes that clashed with their anti-imperialist values. They worried that democratic reform at home could be undermined by obligations abroad.

Some also believed the treaty failed to uphold genuine self-determination, as European powers retained control over mandates. This inconsistency weakened confidence in the League’s moral legitimacy.

Senators were highly sensitive to shifts in public sentiment following the First World War. Many constituents favoured focusing on domestic recovery rather than entering new international obligations.

Influential groups, including some veterans’ organisations and conservative newspapers, warned against foreign entanglements. These pressures made compromise politically risky for senators considering re-election.

Some critics advocated strengthening traditional diplomacy and bilateral treaties rather than creating a permanent international body. They believed flexible engagement protected sovereignty better than collective security commitments.

Others supported international arbitration courts with no binding military obligations. This approach aimed to resolve disputes peacefully without risking automatic involvement in foreign conflicts.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why the United States Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles in 1919–1920.

Question 1: Explain one reason why the United States Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

Identifies a valid reason (e.g., opposition to Article X, concerns about loss of sovereignty, partisan rivalry).

2 marks:

Provides a brief explanation of how the identified reason contributed to Senate rejection.

3 marks:

Gives a clear and historically accurate explanation that links Senate concerns to the broader constitutional or political debate (e.g., Article X obliging the US to defend other nations without congressional approval; Wilson’s refusal to accept Lodge’s reservations).

(4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which President Woodrow Wilson was responsible for the failure of the United States to join the League of Nations.

Question 2: Assess the extent to which President Woodrow Wilson was responsible for the failure of the United States to join the League of Nations. (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

Provides a basic argument addressing Wilson’s role (e.g., refusal to compromise, failure to include Republicans in negotiations).

Includes at least one accurate piece of supporting evidence.

Shows some awareness of alternative factors (e.g., irreconcilable opposition, constitutional concerns).

5 marks:

Develops a balanced argument with clear explanation.

Supports points with multiple relevant examples (e.g., Wilson’s stroke limiting negotiations; Lodge’s reservations; partisan tensions).

6 marks:

Presents a well-structured and well-supported assessment evaluating Wilson’s responsibility relative to other causes.

Demonstrates nuanced analysis of constitutional, political, and ideological factors.

Clearly weighs the extent of Wilson’s responsibility compared with Senate divisions, isolationist sentiment, and concerns about Article X.